Forensics, Franchises and Fans

What “The Grinder” said about television.

When the characters on your TV screen sit down to watch a show, you can almost guarantee that the fake show they are about to watch will have some sort of bearing on their own narrative. Fake shows have their own tropes: they tend to be full of overwrought acting (“Inspector Spacetime” which takes place within “Community”), ridiculous premises (“Mock Trial with J. Reinhold” which takes place within “Arrested Development”), and to make a commentary on the ‘real world’ of the TV show (“Jerry,” the fictional sitcom from season four, directly addresses the audience reactions that “Seinfeld” received, primarily that it is a show about “nothing.”)

Most of these shows-within-shows operate on a comedic level that acknowledges the premise of the fictional universe the viewer is watching, perceptions that audiences have of the show, or makes a comment on the audience itself. “Community” went from Abed being obsessed with “Cougar Town” to being a die-hard fan of “Inspector Spacetime,” a parody of the BBC fantasy series “Doctor Who.” The investigation into the fan community of “Inspector Spacetime” through a focus on cosplaying, conventions, and forums reflected the love fans of “Community” had for Abed and company, despite overall low viewer ratings.

While TV shows may seem to be self-contained universes, the characters need to watch TV shows, read books, and go to the cinema in order to seem real. Sometimes they consume media that is fake—invented for the purposes of the show—and other times it’s entertainment from the world outside their fictional universe. From the friends in “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” being referred to in the show as ‘The Scooby Gang,’ to Joey Tribbianni’s fictional role on “Days of our Lives,” or more recently, Jimmy’s commission to write NCIS novels in “You’re the Worst,” television has often relied on its viewers being fans of the medium as a whole in order to create cultural touchstones. Being referential takes away the need for exposition—we know that Joey will never win an Oscar and that Jimmy has given up on being the next great novelist, purely because of these references to media that we’re already familiar with.

A man looks into the middle distance as a revelation comes to him, and makes a witty remark revealing that he’s cracked the case. Anyone who’s watched enough crime procedurals such as “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation” will know the trope, from a world where solving crime is a sexy enterprise that fits into hour-long slots. Being self-referential allows a TV show to create a stylized hyper-narrative that can operate on multiple levels. In the case of the legal comedy series, “The Grinder,” the function of the show-within-a-show can be read as: providing comedic effect as the main character applies TV logic to his daily life; making a statement on how television affects society’s perception of crime and the law; and as a way to discuss how television works, and the show’s own failings as a sitcom.

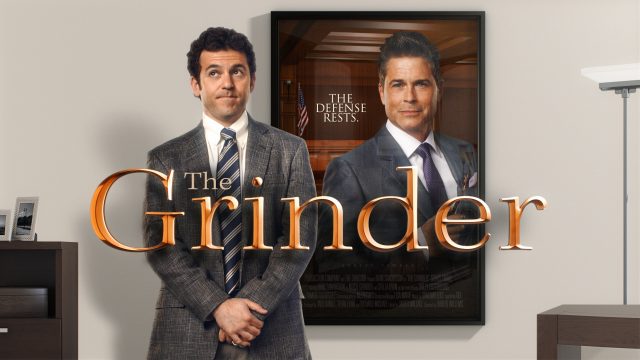

“The Grinder” was released on FOX in 2015, the same year that “CSI” was winding down after a fifteen year-run. It’s set-up as a typical odd-couple comedy: a half-hour sitcom about family life, work, and how two brothers interact when one is a charismatic and idealistic actor, and one is a flustered and down-to-earth lawyer. It’s cast with familiar sitcom faces: Rob Lowe (“Parks and Rec”), Mary Elizabeth Ellis (“Parks and Rec”), and Fred Savage (“The Wonder Years”). The show sets itself up by showing snippets of the show-within-a-show and the reactions of the family as they watch.

Dean Sanderson (Rob Lowe) is an actor who played the character of Mitch Grinder, a criminal justice lawyer who “never stops grinding,” according to the promos. After leaving the show, Dean decides to follow a new career path—joining his father, Dean Sr., and brother, Stewart, at their family law practice, because playing a lawyer for so many seasons surely means he understands how to be a lawyer in real life. Stewart, played by Fred Savage, is flustered by this and tries to show his brother how delusional this is, but fails to get through:

Stewart: “Going from TV law to actual law does have its challenges.”

Dean: “No, that was seamless.”

The initial episodes focus on this odd-couple dynamic and Dean’s lack of qualifications and use of TV logic for comedic effect—in the pilot, a simple housing dispute, Dean joins the counsel gaining media coverage for a small case. Opposing council object to Dean’s courtroom speeches on the basis of one technicality: “Objection, Your Honor. Dean Sanderson is not an actual lawyer!”

The show-within-the-show is characterized by dark filters, oppressive soundtracks, and overly dramatic acting. Initially, the only part of this to carry over to the ‘real’ world of the show is Dean’s use of TV logic. As the season goes on, the diegetics of the show-with-the-show filter into Dean’s world. In Episode Six (“Dedicating This One to the Crew”), Stewart’s son, Ethan, fails to get a part in his middle-school play. Dean vows to get to the bottom of why, and storms out the door, and the score swells in with punchy notes to emphasize this seemingly dramatic moment, which is abruptly cut short by Debbie, the wife and mother of the family, observing that Dean will not be able to go anywhere: “the back yard is fenced in.”

Episode Fourteen, “The Retooling of Dean Sanderson,” takes a narrative structure that would not typically occur halfway through a sitcom season: a cliff-hanger. The episode ends on the news that the firm is being sued for malpractice, and Stewart’s shocked face and the dramatic score would be more suited for the final act of a procedural episode.

Dean’s application of television rules to real life has parallels with the “CSI Effect”, a theory first put forward in 2004 by Richard Willing, which argues that viewers of crime procedurals have forgone the suspension of disbelief and have begun applying television logic to real-life court cases: the District Attorney in Astoria, Oregon, told a reporter in 2005 that jurors wanted DNA evidence for every single case, in his opinion because this is how they saw crimes being solved on television.

Television audiences are expected to put their critical faculties on hold in order to enjoy fantasy. In the case of crime procedurals, this means letting go of the fact that the representations of science and law on these shows don’t ever make sense. Shows like “CSI” invite the viewer to imagine that crime is solved in dark rooms with lab coats and imaginary technology, and it causes difficulty if a jury member expects the court to offer up similar evidence.

As “The Grinder” goes on, TV logic permeates everyone’s perceptions. In episode nineteen, “A System on Trial,” Dean suggests using a focus group while the firm prepares a defence, as he remembers it being useful for TV show production. Rather than focusing on building a case built on empirical evidence, the entire firm instead spends time on how they could win the favour of a jury as though they were an audience. Stewart’s style of presenting facts (which is often fumbling, while factual) is quickly derided as being uninteresting and—unsurprisingly—nothing like the TV show lawyers (“He didn’t say ‘objection’ once,” one of the focus group members barks). The crux of this plot is that the focus group picks up on one crucial point, that Dean Sr. seems to be hiding something when he is questioned. Stewart runs with this theory, and it turns out to be true, proving that in a way Dean was right to use production methods for planning a trial.

Along with a treatise on The CSI Effect, “The Grinder” has a number of commentaries on TV both as a whole, and “The Grinder”’s role with TV. From deriding exposition opening scenes in an age where we can all catch up (“If you’re not following something, then feel free to watch the earlier episodes any time!” is yelled at the screen as the show-within-a-show actors recap previous epsiodes), to Timothy Olyphant (as Timothy Olyphant) hanging around the firm as a form of method acting as he prepares for a show-within-a-show spin-off “The Grinder: New Orleans,” to the final episode which simply has Dean simply stating: “We did it our way…it’s an unusual approach, I’m sure it threw a lot of people at first.”

“The Grinder,” at times, pastiches the show-within-a-show, which is itself a parody of procedurals. The-show-within-a-show deliberately mimics and exaggerates representations of crime on television, while “The Grinder” replicates characteristics of the show-within-a-show visually and through plot points, without exaggerating them. This mixture of parody and pastiche means that it can be enjoyed through multiple layers of irony: a parody of procedurals, a parody of show business, and a commentary on how television can affect our reasoning in our everyday lives. According to the cultural critic Linda Hutcheon, pastiching is a valuable cultural commentary precisely because of its apparent emptiness: the audience is smart enough to realize what is happening on screen, and will draw their own conclusions about the pastiched work.

The nature of both sitcoms and procedural dramas is to create episodes that can both be enjoyed as a standalone story that can be dipped into, or enjoyed on a weekly basis through a narrative arc. “The Grinder” fails to do this—Episode Nineteen loses half of its comedic effect if you haven’t watched the build-up of Stewart slowly coming around to TV logic, and the family drama of Episode Six would seem unnecessarily dramatic rather than framed through an ironic lens.

The show relies on the cultural memory of how TV works, and it was loved for its commentary on the medium itself: it had a 93% critics’ approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and it garnered Rob Lowe a Golden Globe nomination. Yet it bombed on ratings, and failed to make it past the first season, because it was far more suited for streaming than for weekly episodes (the same fate as “Community” and “Arrested Development,” which were both resurrected on streaming platforms after cancellation.) It’s a move from sitcoms where audiences could easily picture themselves in the narratives to meta-comedies that require the viewer to watch the whole season in order to get the jokes.

“The Grinder” is a show for committed fans of the medium: fans who will commit to every episode, who will pick up on cultural touchstones, that will recognize the effect TV has on society and understand that the joke is about the viewer’s own relationship with popular culture. It’s a sitcom that isn’t suited for TV, even as it attempted to exist on FOX so it could be part of the joke, because it couldn’t find an audience large enough to commit to the bit that perhaps we all watch a bit too much TV.