Between Night and J'ouvert

On the summer that threw us off our moral circadian rhythms.

Image: Michael Dougherty via Flickr

The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward schadenfreude. How else to explain the karmic perfection of a solar eclipse captivating us in the summer of 2017, a season when we’ve shown a feeble ability to know darkness from light? I think of Baltimore and Austin, moving under cover of night to remove Confederate statues. And of New York, forcing J’ouvert, the pre-dawn celebration that sets the rhythm for Crown Heights’ West Indian American Day, well past the ability to deliver on its translation. The word means “daybreak,” a detail the event’s new start time, six in the morning rather than four, blithely obscures. According to the New York Times, metal-detecting checkpoints designed to ferret out troublemakers are being imported from the city’s handling of New Year’s Eve in Times Square, an event pointedly allowed to remain oriented toward midnight. “The biggest thing for us is sunlight,” a mayoral task-force member told the paper, of the changes to J’ouvert. “We believe that light is a big deterrent.”

Both these scheduling feints are intended to stem violence: Nocturnal statue excision, in avoidance of Charlottesville-style clashes; J’ouvert’s move, thwarting a small contingent who bring guns or knives, looking to settle disputes. And both departures from the norm can be interpreted as disrupting a tradition. Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh was quoted in the New York Times as saying she felt the city’s Confederate-era statues should be removed “quickly and quietly,” not so much ripping off a Band-Aid as a scab. Also from the Times report: The quickness and the quietness of the removal was such that City Council President Bernard Young did not learn of it until he woke up the morning after. Young “missed a late-night phone call from the mayor because he had taken cold medicine for bronchitis and was asleep.” Each generation gets the consciousness-altering substances it deserves.

I watched the eclipse from Brooklyn’s Fort Greene Park, where a young woman moved deliberately through the crowd, carrying a burning cone of sage in such a way the fumes had opportunity to purify us all. It was the personal made political, like aiming cologne on the subway not so much at yourself as the offending passenger next to you, except she was aiming at our souls. Complete darkness did not fall, only a grave light resembling the Instagram filter Perpetua, but it was still disorienting, as nature intended.

The event capped a summer of willful dimness all around, as bodies politic crossed paths, disagreeing even on whose was the dominant orbit. Shortly after the eclipse, the controversy around the Crown Heights cocktail bar Summerhill flared again, as if animated by tidal pull.

Becca Brennan, Summerhill’s owner, attracted a well-organized neighborhood protest earlier in the summer after encouraging an interpretation that pockmarks in her industrial-chic walls were bullet holes.

“I’m sorry I have a sense of humor,” Brennan said last week, at a town hall meeting to air complaints. She argued for “keeping the integrity of this 100-year-old building,” right after admitting the holes in the wall most likely remain from bolts anchoring a defunct bodega’s refrigerated cases in place. Diana Richardson, who represents Crown Heights on the New York Assembly, threw the essential concepts into bold relief. “People have died in this community,” she said. “There’s nothing about the architecture to protect, you know?”

![]()

Certainly it’s a form of privilege, a fluidity in attributing damage to gunfire one minute, soda cases the next, and all along claiming history is on your side. I tried to let that recognition burn my way, like eclipse sage. Last summer, under the guise of “research” (I could not quite articulate for what—maybe an article, maybe fiction), I had talked my way into one of Crown Heights’s numerous mas camps. The camps (the “mas” is short for masquerade) function as workshops and showrooms for the costumes displayed at the West Indian American Day Carnival, on Labor Day.

The mas camp I visited was installed in a standard city storefront, a slender floorplan familiar from cell-phone repair shops to artisanal cheese counters alike. When I arrived, I was fed roti and left to explore the glossy, jet black mannequin torsos leaning from the walls, like the mirrors of fable that go liquid and climb into the world when awakened by the right incantation. The mannequins were dressed in the jeweled, feathered harnesses and bikinis familiar from the Labor Day parade, intricate stitching and ornamentation that represents not only hours of work in shops and at dining-room tables but also sizable annual contracts with the notions and trimmings shops in Manhattan’s garment district. (The mas camp I visited, like many, creates regalia for a year-round, global Carnival calendar, not just the New York version.)

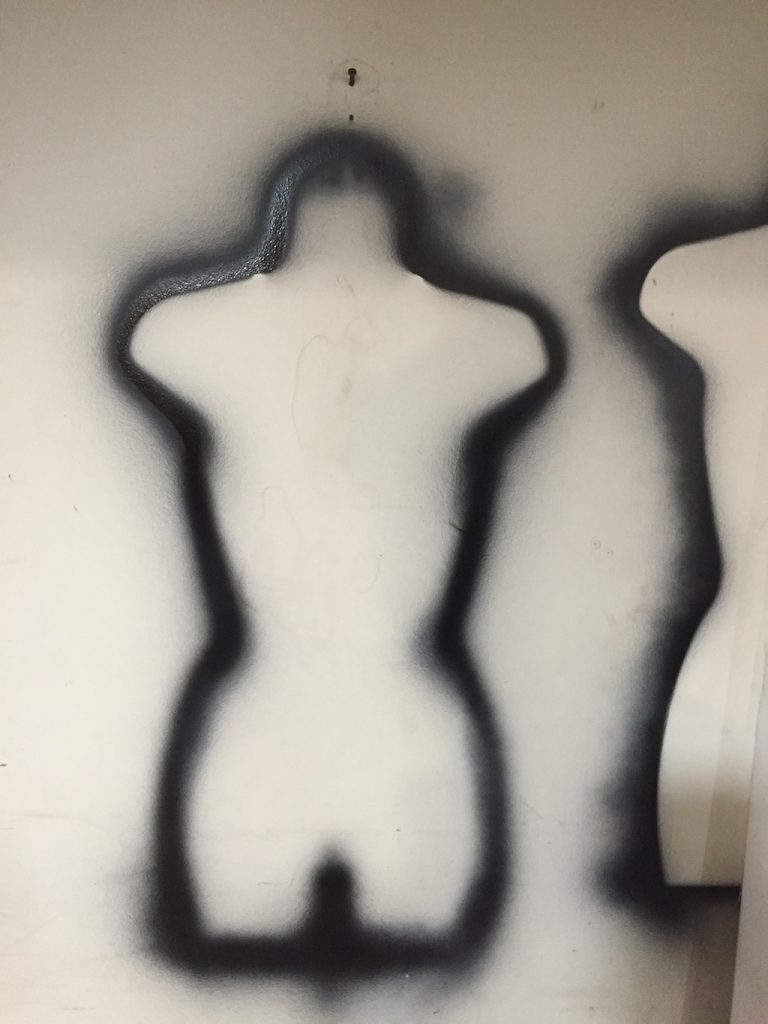

The street-level storefront was for display and ordering, and I was also shown the basement level, a warren of rhinestones, hot-glue guns and leaning bolts of jersey, cooled by oscillating fan. On the white wall, I noticed a repeating pattern of black striping in human form, contours that formed an empty chest, shoulders, and neck. It took me a moment to understand the outlines were the halo effect of spray-painting mannequins that had arrived in tones of “nude”—that is, the white version of nude—so they could gleam the shade of black I’d seen upstairs. Still, I had trouble shaking the idea that the silhouettes resembled shooting-gallery targets.

Was my instinct to see gunplay on the wall where there was none any purer than Becca Brennan’s? There are degrees of illumination (light bulb, tiki torch) but I don’t know that the same is true of taking advantage of privilege. The motivations can be disingenuous, like claiming reverence for divots in the wall or statues on the lawn one never really sees, or merely obscure, like being unclear, even with yourself, about why you’re showing up someplace with a notebook and pen.

I’m a little clearer on what, exactly, I was doing with a notebook and pen a few years ago, at another of the Confederacy’s alleged last gasps, taken under the cover of night. On assignment from the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, I’d driven down from Little Rock to the kind of South Arkansas estate that still had a name—Beau Geste (“beautiful gesture”) comes to mind, though the particular notebook in question is lost to history—to cover a kick-off dinner for a local film festival, chiefly because the guest of honor was Jane Russell, who sang “Just a Little Girl From Little Rock” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. After dinner, and this part had nothing to do with Russell or even, properly, the festival, the shades were drawn and dinner guests were invited to stay for a clandestine screening of the old Disney film “Song of the South.”

I’m a little clearer on what, exactly, I was doing with a notebook and pen a few years ago, at another of the Confederacy’s alleged last gasps, taken under the cover of night. On assignment from the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, I’d driven down from Little Rock to the kind of South Arkansas estate that still had a name—Beau Geste (“beautiful gesture”) comes to mind, though the particular notebook in question is lost to history—to cover a kick-off dinner for a local film festival, chiefly because the guest of honor was Jane Russell, who sang “Just a Little Girl From Little Rock” in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. After dinner, and this part had nothing to do with Russell or even, properly, the festival, the shades were drawn and dinner guests were invited to stay for a clandestine screening of the old Disney film “Song of the South.”

This veil of secrecy was pulled because the film was understood even then to be problematic in its depiction of plantation life and of “Uncle Remus,” a former slave. Though elements from the animated portions of “Song of the South” persist in Disney World’s Splash Mountain attraction, the film never received home-media release in the U.S., only in parts of Europe, Asia, and South America (the copy used for the screening that night featured Korean subtitles. I was seated next to the sole African-American guest, a professor from the University of Pine Bluff. When I asked for her opinion of the film, she declined to give one out of “respect for our hostess.” Talk about a beautiful gesture.

In any case we never finished the film. Near the end, there was a slump and a clatter in the back row as an older man slipped from his folding chair to the floor. The lights came up and, ashen-faced, “our hostess” stood and craned her neck toward the disturbance. “Who is it?” she asked fretfully, a more pressing question, it seemed, than “what happened?” What happened was the man merely became overheated and fell asleep, but the damage was done. “Song of the South” played on, under overhead lighting that washed out the images on the screen so that everyone resumed chatting, as they had at dinner.

The state of Arkansas was inserted uncomfortably into recent post-Charlottesville analysis, by way of a tiki-torch-bearer who’d been photographed in a red T-shirt bearing the white lettering, “Arkansas Engineering.” The modern, online form of standing up and calling out “who is it?” is known, of course, as “doxxing,” and sometimes can be imprecise. The T-shirt wearer was initially misidentified as a University of Arkansas College of Engineering professor who shared a resemblance to the protester, until the Arkansas Times ferreted out the actual man from the photograph, Andrew Dodson, who’d merely spent time at the college as a student.

In an interview, Dodson expressed regret the professor had been subjected to harassment and threats. In mind of everyone he’d encountered in the engineering program, he said, “it breaks my heart that they’re going to think I’m a Nazi, or a KKK, or a white supremacist.” I suppose Dodson thought of this as some kind of beau geste, but he was unable to convincingly explain what separated him from the other men in Charlottesville who’d held tikis and chanted phrases like “Jew will not replace us,” even while photographic evidence existed of him holding a torch and composing his mouth as if in speech. Some dark nights of the soul resist illumination, no matter how close you stand to the flame.