The Radical Grace of Gengoroh Tagame

‘My Brother’s Husband’ and the tradition of gay manga.

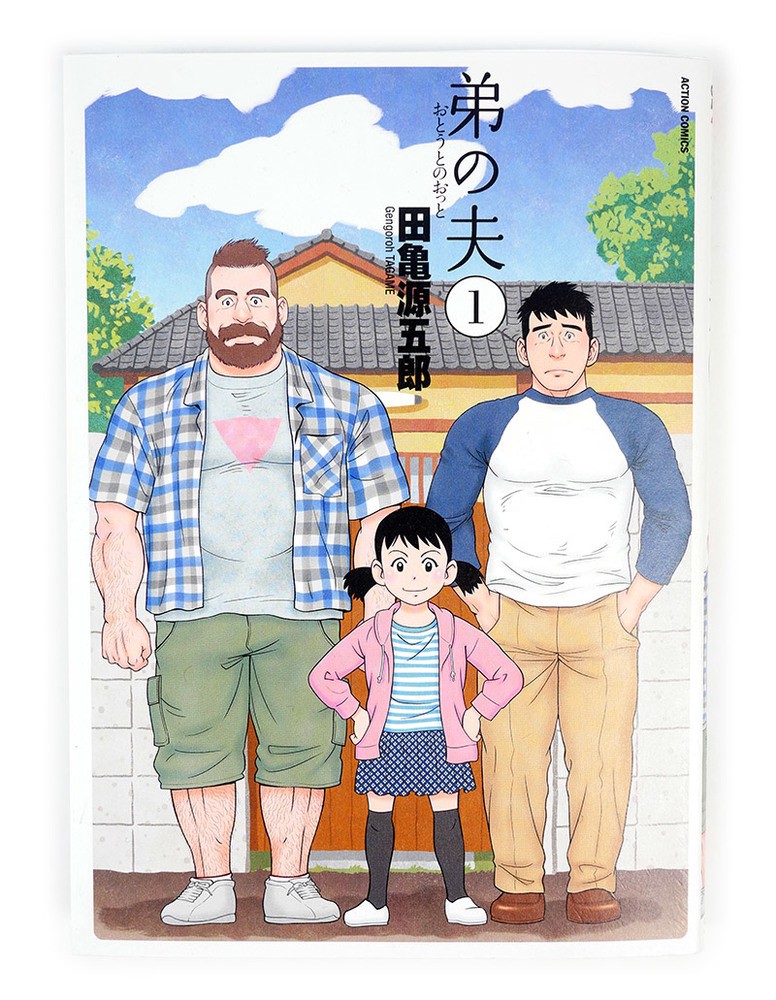

In the first volume of My Brother’s Husband, the Japanese manga created by Gengoroh Tagame, a single father hosts the spouse of his dead twin brother. After his sibling’s death in Canada, Yaichi and his daughter come to terms with it, while his brother-in-law, Mike, navigates Tokyo’s suburbs for the very first time. They settle into a wavering domesticity. That the story isn’t entirely tragic is a testament to the author’s mastery: widely described as “Japan’s most influential gay manga artist,” Tagame is playful throughout. He is assertive, occasionally goofy, and forgiving with his characters, and as Yaichi picks apart the walls of his ignorance, the narrative allows him the room to grow.

As Alison Bechdel has noted, the work is “very different from [Tagame’s] customary fare”; the artist’s oeuvre is generally queer, but it’s also a good deal more explicit. His narratives usually delve into BDSM, and S&M, lingering on the extremes of human sexuality. Since the ’80s, Tagame has pushed the boundaries of what was “allowed” in gay manga. But My Brother’s Husband is largely sexless. It’s very nearly chaste, and (almost) entirely safe for kids. And, as a whole, the work might be even more revolutionary than anything he’s produced before.

Tagame works in a sub-genre of manga called bara, which is itself a cousin of yaoi, which can be loosely defined as “boys’ love” (it’s an acronym derived from yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi; or, “no climax, no point, no meaning”). Jamie James, in an essay for The New Yorker, notes that the genre “was coined in the nineteen-eighties to identify sentimental stories about beautiful boys”:

In its essentials, yaoi is an updating of the cult of boy worship in feudal samurai culture, known as shudō, the Way of the Boy, in which an adult warrior took an adolescent disciple as his lover. In the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867), this pederastic arrangement was not only tolerated but normative, regarded as a more refined taste than the love of women, with spiritual connotations. The seme–uke dichotomy in yaoi fiction follows the samurai model, with the key modern innovation that the lovers are the same age, or nearly.

But while yaoi is generally marketed with a female audience in mind, and plots whose formulas skew towards more heteronormative norms, bara is almost always created by and for gay men. While yaoi’s character’s often don’t identify as homosexual, the opposite is true of bara. Yaoi’s characters are slim in proportion, while bara’s are muscular, if not bearish, damn near all of the time. And if yaoi doesn’t always belie sex, bara’s intercourse is multi-paneled, explicit, and occasionally fetishitic; but, in a funny way, it makes sense that the genre’s most revered practitioner has conjured a loving portrait of a man just beginning to reckon with the layers of sexuality.

Distributed and translated by Pantheon Books, My Brother’s Husband is one of Tagame’s first legally distributed English publications. But American readers aren’t entirely unfamiliar with his work. In 2013, PictureBox published The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame, a sold-out compendium. Gmunder Books has regularly published him in English since 2014. My Brother’s Husband netted Tagame a Japan Media Arts Award from the Agency of Cultural Affairs (a big fucking deal), and, with the series, a creator whose work couldn’t have otherwise have surfaced in polite conversation has garnered praise and widespread adulation.

In interviews, Tagame is very self-aware. In a chat with the Huffington Post, he noted the structural differences, saying he was “much more careful and deliberate about the art then, so it wasn’t as much about the story. It was about the graphics. It wasn’t pornography, and it didn’t depict sex; it depicted eroticism.” But Tagame hasn’t sweated the implications of the change in his aesthetic too much either, and talking with Chris Randle over at Hazlitt, he notes that, “in stories and in eroticism, I’m very particular about heroes, and I’m very concerned with the idea of the hero, but the hero that I fantasize or dream of isn’t someone who builds nations or brings peoples together, but a person who’s falling apart.”

Throughout My Brother’s Husband, those same sentiments are embodied by Yaichi: he is constantly coming to terms with himself. First, he navigates his brother’s homosexuality. And then his revulsion towards it. And then his daughter’s unvarnished acceptance, and the apprehensiveness of his neighbors, and watching him reckon with his brother’s ghost is as affecting as any conflict in literature. At one point, after Mike explains that there was no “female” in his marriage (“We were husband and husband”), it takes Yaichi watching the epiphany spread across his daughter’s face to jumpstart his own illumination. “I had no idea,” Yaichi says, staring into nothing, “About any of it.”

The work’s acclaim in Japan is a minor miracle: despite recognizing same-sex partnerships in a handful of Tokyo’s wards, the nation as a whole is largely apprehensive towards same-sex marriage. There are Pride parades in the larger cities, and a scattering of gay bars in those same hubs, and the threat of physical violence may not be as high as in some countries, but social stigma, from the outset, is a big enough deterrent to keep folks from living openly.

But Japan rewriting the rules for gay fiction shouldn’t be entirely shocking, either: the country’s culture has made space for male-on-male sexuality in print since the seventeenth century. From Ihara Saikaku’s story collection The Great Mirror of Male Love (1687), to Utamaro Kitagwa’s erotic wood prints, to Ogai Mori’s novel Vita Sexualis (1909), Japanese artists have investigated the contours of gay love, free of the West’s religious stigma, for centuries. What isn’t entirely accepted in public has been given free roam to expand on paper, and it could be as Yukio Mishima alludes to in his novel Confessions of a Mask: “Prudery is a form of selfishness, a means of self-protection made necessary by the strength of one’s own desires. But my true desires were so secret that they did not allow even this form of self-indulgence.”

Since the ’90s, the American entities publishing gay manga in translation have continued to expand, chipping their way around the mainstream. But their prevalence in the States’ comic culture isn’t nearly as expansive as the medium’s counterparts: ever since the introduction of series’ like Lone Wolf and Cub, Appleseed, and Sailor Moon around the late 80’s, American comic publishers began investing in manga as a business booster. Animated franchises like Dragon Ball, Akira, and Neon Genesis Evangelion multiplied this expansion in the 90’s, before Pokemon solidified it; and Japanese publishers set their own sights on the stateside market shortly afterwards. But of the manga and anime series’ that have made it big in the States, none are overtly gay. And while, a fraction of a fraction the time, a series suggesting homosexuality slips through the mainstream, until the early-aughts your best bet for finding bara and yaoi were the illegally scanned translation hubs pocketed across the internet.

But while the scanlation hubs persist, a handful of American entities are legally publishing gay manga. And some like MASSIVE GOODS, have worked every available angle (to great success), from manga to apparel to accessories, gaining notice from Out to MTV to the New York Times. Founded by Anne Ishii and Graham Kolbeins, and currently helmed entirely by Ishii, MASSIVE has gained a substantial following since its inception in 2013. But as Ishii, corresponding over email, put it to me, with “what felt like a clearly profit-less book model, it felt obvious to start a fashion line”:

If I were to say one thing about the MASSIVE aesthetic, it is maximalist. Speaking only for myself, minimalist trends depress me. I mean I love clean lines and gajillion dollar Eames chairs like everyone else but I also cringe around Helevitca. I want to feel like I’m being hugged by design, not being delivered an SAT exam. Graham and I have both been fond of the bold and the large and the beautiful. Chip Kidd, who contributes to our aesthetic, and designs all the books, is also a sort of a maximalist, in my opinion. I’ve tried to make what I think are relatively “safe” designs, but perhaps because the intent is visibly disingenuous or because our fans have so firmly made their imprint, the “safe” things don’t move with the alacrity of our massive looks

Ishii noted that “gay manga to many people is content that supersedes whether and how it is sanctioned.” And, in this way, the publication of My Brother’s Husband, from a major publisher is a quiet, sonic achievement: an art form whose primary audience could’ve only been grown on the outskirts of the internet has entered the American book sphere.

Tagame is clear to distinguish between pornography and eroticism; and despite its lack of obvious sexual tension, the men in My Brother’s Husband are definitively beautiful. The lines are full and bold. Their bodies are stout. The expressions on their faces are emotive in one panel, and aggressive in the next, before that anger dissolves entirely on the following page. Of course Tagame’s a veteran of his form, and a master in the craft, but the emotion in his work doesn’t always connote to sex. Sometimes, the subjects are a means to beautiful art. And, as he notes in an interview with The Huffington Post, that Tagame has molded his abilities to realize these very particular narratives is shocking, and heartening, and wholly inspiring:

“At home, we had anthologies of classical art, and I was highly attracted to and influenced by the Hellenistic period. The most modern I went to was probably Baroque and pre-modern. In what I’m depicting as sexual humiliation, Western religion is a big influence: Caravaggio’s depictions of Christ’s humiliation or his crucifixion, obviously. Things like that are in line with what I want to depict. Conversely, in the Japanese artistic tradition, there isn’t really praising the nude. There are certainly depictions of violence, but there isn’t a tradition of just the full male nude body. So in that sense, Western religious art has been a huge influence.”

It mirrors a sentiment that Samuel Delany, a noted fan of bara, expressed in last month’s interview with The Boston Review

Not all explicit sex is pornographic. It can be educational, and I expect that a room full of forty to eighty year olds having sex and discussing their lives would be just that: educational… They aren’t breaking any laws. They’re enjoying themselves and caring for their own community. And they’re talking honestly and intelligently.

Sometimes, that beauty incarnate is the goal. Depicting it in a very particular way, for a very particular audience, absence of erotics can prove erotic enough. One bara artist, Inu Yoshi (himself drawn to gay manga through Tagame’s work in G-Men magazine) has said, “I don’t really want to put erotic scenes in my stories, but it’s what sells magazines, and the magazines say it has to have that.” Another creator, Fumi Miyabi, describes his own work as directly influenced by that aesthetic, noting that, “I saw Tagame and Go Fujimoto and Keiichi Takasaki. I saw what I imagined gay erotic comics were supposed to look like, but it wasn’t just gay — it was also really great manga.”

Some artists are attracted to the aesthetic. Others are drawn to those came before them. And for others, as Tagame has elaborated for Vice, the distinction between those two impulses is infinitesimally small:

Porn is a search for the perfect erotic expression. It’s not necessarily self-assertiveness, nor a status symbol, but uncontrollable desires. Pursuing such pure pleasure is less complicated. In such pursuits, pornographic art is pure, fine art. My goal is beyond manga or porn, but to aim for the level of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

There’s a moment in Édouard Louis’s novel, The End of Eddy, where his narrator turns to the moment he acknowledged the “pain” of his sexuality:

I thought that in the end I would get used to the pain. There is a way in which people do grow accustomed to pain, the way workers get used to back pain. Sometimes, yes, the pain regains the upper hand. They don’t get all that used to it, really, they work around it, they learn to hide it.

Tagame’s work covers a sort of pain in its own right: the pain of loss. The pain of difference. The pain of becoming something else, something new. Throughout My Brother’s Husband, Tagame’s characters are constantly coming into themselves, but the most affecting moment could be a scene, late in the volume, when a neighbor’s kid skips school to approach Mike in Yaichi’s home: “I came over here,” he says, “A few times to see if you were real.”

“All I think about are boys… and I realized that’s always been the case. I’d heard things: homo, gay… I knew about it, but… I didn’t know who anyone was. Nobody I knew anyways. When I looked online, I realized there were a lot of people like me. And I felt better. But some people wrote nasty things. I got little scared, and I realized I should probably hide this.”

“So I deleted my history,” says the kid. “I pretended not to care.”

Any motion to tell gay stories is a lantern in a dark, crowded room. All of it always matters. And, on paper, an artist working within such a niche genre, in a form supporting reams upon reams of content, shouldn’t exactly be earth-shattering. But in forcing his characters to come to terms with themselves, Tagame challenges his readers to do the same.