Napkin Tricks From Old New York

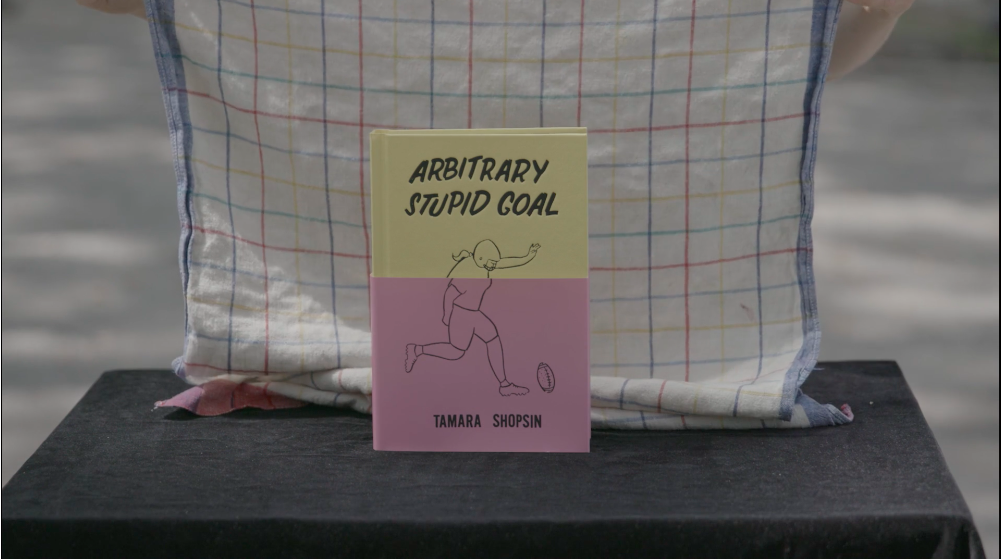

Tamara Shopsin, ‘Arbitrary Stupid Goal’

“That’s just roasted potatoes and zucchini,” the artist, writer, and cook Tamara Shopsin said, cheerfully, as screechy feedback interrupted our phone call, signaling, presumably, that her dinner was ready. She joked about the priority the meal took over talking about her book, echoing her press-averse father, Kenny, who’s been called Buddha and compared to the Soup Nazi.

The book is Arbitrary Stupid Goal, Shopsin’s second memoir, and it chronicles her life growing up at her family’s general store-turned-restaurant in New York City’s West Village, with her parents, four siblings, and one larger-than-life family friend, Willy, who should unquestionably have his own biopic by 2020.

It reads like you how dream that telegraphs once functioned, or wish text messages worked today. Every anecdote is a taut, warm, fully immersive plunge into the West Village of the ’80s and ’90s that returns you to the surface well before you ever require oxygen.

You’re in a boiler room apartment, feeding an old man or giving him a bath. You open the store to find regular John Belushi (who had his own set of keys) passed out in a chair. Your neighbor earns cash on the side by tying up dudes in his mirror-ceilinged fuck pad. Your dad Kenny is telling a customer to get the fuck out because they threw off the balance of the store.

It all happens in a world post–Etan Patz and pre–Find My iPhone. The Shopsin parents trusted that their kids wouldn’t mess things up too bad, and empowered them to be whoever the hell they wanted. Shopsin’s 8-year-old brother survived a solo subway mission to the Museum of Natural History, thanks to his resourcefulness and access to a payphone. Another brother was gifted an early Apple computer when the family couldn’t afford it, because their parents could see how passionate he was.

“I don’t know what the reverse of a helicopter parent is, but that’s what my parents were,” Shopsin explained, letting her dinner get cold. “We were allowed to wander by ourselves. It was heaven on earth. My parents were very Zen.”

The neighborhood could be dangerous. The shop got stuck up, a lot. The AIDS epidemic bewildered everyone. And there were “lowlifes” on the block. Once, after a neighbor expressed interest in a little girl, he was kept at arm’s length, but the police weren’t called. People had conversations and (sometimes reluctantly) helped each other out.

Arbitrary Stupid Goal never feels gauzy or nostalgic—no one pines for an era when a neighbor made sure to call you a fat Jewish bastard every time you came home. The reader is left realizing that it’s pretty weird to live in a city of eight million people whom we mostly successfully ignore now, even when we’re wedged together in a failed subway car.

Shopsin’s sketches end when they need to. As in her previous memoir, Mumbai, Scranton, New York, the book’s layout reflects this efficiency. And the rhythm she establishes in the process, both rewards attention-challenged minds and leaves them wondering, “Then what happened?”

To Shopsin, “What happened,” is all in the book. And if it’s not, you don’t need to know. Especially if you’re some creep calling her up asking about her life. I learned as much when we set out in her new neighborhood — which she’d prefer no one knows about—to hunt for a good spot to film the napkin-folding video above (a customer taught her these tricks when she was little). She was amiable, but reluctant to talk much about herself. So much so that I said to her, “Treat it like a game show. Just say ‘skip’ or ‘pass’ when I ask you something you don’t wanna talk about.”

Later that day we spoke on the phone. In advance of many “skips,” she laughed and told me I created a monster. She talked at length about the best kitchen burn cream — Silvadene, but not much else, and the interview was put out of its misery, leaving the book to do what it was intended to do.

‘Arbitrary Stupid Goal’ is out July 18 from MCD/FSG Books.