Guster's Ambivalent Nostalgia

Where it’s always balmy summer or a gently crisp fall.

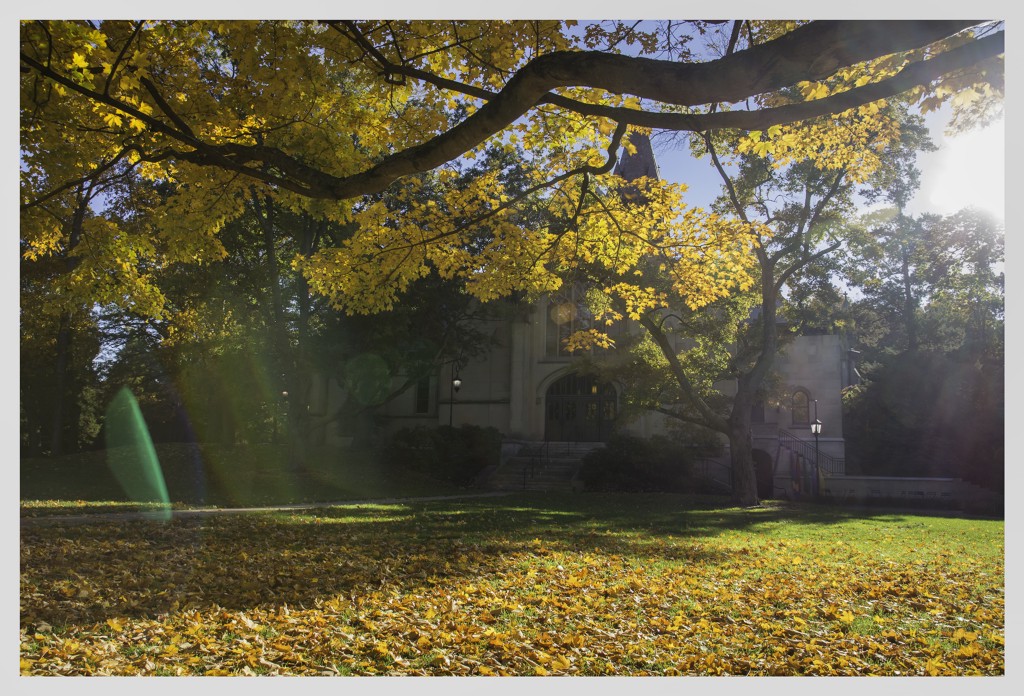

Over the course of my tenure as a Guster fan, I attended only one of their concerts. They performed at my alma mater, the College of William and Mary, on Homecoming weekend the fall after I graduated. That’s a fitting context for a Guster show if ever there was one: inside a gasp of collegiate nostalgia, where I was both haunted and seduced by my past selves. At the time this felt like comfortable pseudo-regression. I wasn’t ready to be somebody else yet.

Thankfully, Guster doesn’t write the sort of songs that demand assertiveness or resolution — though they do often articulate that aspiration. Guster, I learned when I discovered them in high school, invites us to dwell in queasy uncertainty, the variety that accompanies our most capacious experiences: alienation, deceit, love, time’s passing. And they’re always looking back, though their vantage point is vague, a roving dot that elides firm position. There are bands we return to because their sound lassos old memories that, at the time, were fledging moments. That’s one way to indulge in nostalgia and, of course, Guster summons this effect like any other musical relic from the past. But they also trade in the experience of nostalgia — its thick, heady atmosphere: their music revels in it, turns it over, and examines its contours. Guster invites us to tarry in nostalgia for its own sake.

There’s something peculiar about this, because the band’s music has always struck me as fundamentally atemporal. It’s a matter of form and affect more than particularities of content. Inside of a Guster song, it’s always balmy summer or a gently crisp fall, unless — in the case of “Rainy Day” — foul weather is the point. Technology is generally unremarked upon, save for in the broadest strokes — a stray reference to MTV or a track entitled “Airport Song.” Instead, lovers write letters to bridge distance or meander through the May parade, quietly mulling over their soured romance. And while we can pinpoint Guster’s heyday as the stretch between the late nineties and early aughts, the band has never fit comfortably within a genre, unless of course you acknowledge their ubiquity within college a cappella circles.

Yet Guster’s soul is fixed, at least geographically. They were founded by Adam Gardner, Ryan Miller, and Brian Rosenworcel at Tufts University, taking shape in early ’90s New England with an intimate but devoted following. In 2003, multi-instrumentalist Joe Pisapia joined the fold, but departed seven years later in 2010 (Luke Reynolds took his place). With the exception of some colonial flair, Boston and Williamsburg, Virginia share precious little in common. Nonetheless, I felt — or fantasized — a kinship with Guster because I craved a world that was as vivid and earnest and picturesque as their songs. That is how I both envisioned college and how I remember it now.

Guster’s shtick could seem hokey — misty watercolor memories, and all that — and their sound overly precious, but neither was the case. Their Garfunkel-esque harmonies retain raw edges, and when necessary, the robustness of their percussion signifies emotional urgency. There’s pain inherent to both hope and reminiscence, Guster reminds us. Ideals are spun from disappointment and sorrow, whether we’re gambling on the future or aching to recall a time better than the present.

This is to say, what is most poetic about Guster is their ambivalence. “Come Downstairs and Say Hello,” a slow-swelling wallop from their 2003 album Keep It Together articulates the solicitude beneath defiant claims of change. “To tell you the truth, I’ve said it before / Tomorrow I start in a new direction,” Ryan Miller intones, “One last time these words from me/ I’m never saying them again.” Both the rhythm and Miller’s voice gradually grow more confident — “I look straight at what’s coming ahead / and soon it’s going to change in a new direction,” he declares — but as the melody waxes we’re carried away not by surety but by the desperate hope of wearing it as a mask. And yet, when it comes to Guster, neurosis rarely registers as jagged or dissonant. On the contrary, “Come Downstairs and Say Hello” features some of the band’s sweetest, most transporting harmonies. The yearning in Miller’s vocals and eagerness in the percussion burgeon, but maintain a steady cadence. This seems to be the point — that anxiety is threaded into our lives so intimately we can scarcely detect its origins. We’re always sliding around on a continuum of fear; we manage how we can.

“Come Downstairs and Say Hello” strikes me as one half of a pairing: the latter, more mature half. Its earlier and perhaps more self-indulgent variation is “Two Points for Honesty,” the penultimate track on 1999’s Lost & Gone Forever. There’s less subtlety here, in lyric as well as in melody — and instead of timid hope, pessimism wins the day. Again, Guster’s speaker contemplates the future with potent longing, but this time is swallowed by self-defeat. No welcoming voice issues an invitation to “come downstairs and say hello,” no one reassures, “don’t be shy.” Instead, as the dulcimer shivers, the speaker arraigns himself via projection. “It must make you sad to know that nobody cares at all,” Miller warbles, in mellow self-condemnation.

In the case of “Two Points for Honesty,” Guster’s juxtaposition of choirboy melody and bitter self-interrogation — generally held in delicate balance — slumps heavily with nihilism. It’s the perfect song for wallowing, which is why I loved it in high school and perhaps, to my chagrin, why it can’t supply me with the same pleasure now. In adolescence, there is an insolent comfort to proclaiming oneself alienated, or even a lost cause of sorts. After all, the former is often the case, at least to some extent — admitting that can be a relief. As teenagers, we’re the cruelest we’ll ever be, to ourselves and to each other. In that raw time, we’re sometimes more comforted by what feels true, whatever the empirical data. And we’re always vulnerable to the terror Guster acknowledges: we want something better, and we’re sure it doesn’t exist.

What Guster understands, and what they’ve always articulated so exquisitely, is that we’re perpetually yearning both backwards and forwards. When, at 15, I heard “Either Way” for the first time, its delicate melancholy elicited an ache for loss I hadn’t yet endured and couldn’t possibility understand. Yet it was just as easy to contemplate the decade and a half that had already passed. After all, from the time we are young we learn to dwell in memories; it’s a consequence of thinking. Guster welcomes us wherever we are, invoking tender, if bittersweet, reflection upon all that we have ever felt, or will feel.

At the end of their William and Mary Homecoming show, Guster asked the crowd to participate in an experiment. Rather than depart the stage, in anticipation of an encore, the band asked us to turn away and stand with our backs facing them. On the count of three, we complied en masse, and for a few moments, our bodies pulsed with swollen silence. I was impatient and uncomfortable, but I had felt that way all day.

“This is fucking weird,” Miller said.

We turned and assumed our previous positions on the grass. I’m not certain that they played “Homecoming King” next, but I prefer to remember it that way.