Go Independent Or Go Home

How leaving big publishing for a small press made me a better writer and happier person

Today, my second novel is being published by an independent press based in San Francisco. It’s technically a “soft launch,” meaning the publisher — Fiction Advocate — will start shipping copies to anyone who orders direct, with the official/Amazon pub date pushed back a month, to August 22. (The book also costs $5.00 more on Amazon and won’t include shipping and handling.) Economics drive this strategy: with the unit cost around $5.50, and Amazon charging something on the order of $18.50 to sell a $25.00 book, it leaves the publisher with about $1.00 profit per copy on Amazon sales. For direct orders, by contrast, the publisher keeps $20.00 minus the unit cost and two or three dollars for shipping, which is included. My royalty — 10 percent, which is based on net profit (the money the publisher receives for the book) — is $2.00 per copy on a $20.00 direct sale versus $0.10 or $0.15 for an Amazon sale.

The goal: If the publisher — which pays no author advances, salaries, or office rent — can sell a few hundred copies direct and a few hundred more through their independent, non-gouging, non-Amazon distributor, they will make back their costs and some extra, which they’ll put into their next project. (My royalties should pay for a few nice dinners in New York City?) So far, over three years of operation, their growth has been slow but steady; mine is one of a handful of books they plan to publish in the next year or so.

The five remaining major trade houses in the United States — aka Big Publishing (click here for insane chart) — do not have this flexibility; to show even modest gains, they must publish increasing numbers of books. Following the decimation of brick-and-mortar bookstores, they rely on Amazon to sell enough copies to cover author advances, office space, employee salaries, and whatever else they spend money on. While their margins are higher than an independent on a per-book basis, thanks to bigger print runs and a (somewhat) better take from Amazon — not to mention far greater sales numbers for (some) titles — their long-term prospects are increasingly murky.

A few things are happening. The first is that we don’t read as many books as we used to. You know this is true. We watch television until it hurts and then we watch even more television. We spend hours crying silent tears of agony as we scroll through our Facebook and Twitter feeds. If you spend your days making a living on a computer screen, the idea of picking up a book can feel like punishment. Words have never been more exhausting, which is bad news if you want to sell thousands of books.

Second, as with the music business, books have become “nichier,” which makes marketing a trickier proposition. Genuine blockbusters are increasingly rare, and books with sales of a few thousand copies appear on bestseller lists. Third, book-making technology (again, like music), has become cheaper and more accessible, producing books that look and feel as good as, if not better, than those made by Big Publishing.

Facing all the above and strapped with shrinking profits, clunky legacy systems too expensive to replace or upgrade, and bloated management hierarchies (seriously, did you look at that chart?), Big Publishers have tried to maintain bottom-line revenue by cutting costs through consolidation, layoffs, and greater use of freelancing and outsourcing. The predictable, undeniable result is that their books are shoddier and their staffs — particularly at the ground level, where most of the important work of publishing gets done — are overworked and underpaid. Extinction for these publishers may not be imminent, but it’s inevitable.

Have you seen “Colony?” It’s a television show on USA about what happens to Earth in the wake of an alien invasion. The aliens (never shown, except for their killer drones) have surrounded L.A. with a gigantic wall and installed a puppet government. While most of the population scrapes by in urban squalor, officials and their families live in a “Green Zone,” a manicured, gated community that offers its inhabitants all manner of pre-invasion amenities. While superficially calm, life in the Green Zone, thanks to insurgents who sneak on and off the premises to commit acts of violence, is increasingly chaotic. If the officials can’t control “the insurgency” and — by extension — the larger population, the aliens may decide to kill everyone and turn the entire city into a parking lot.

I’m not here to recommend the show, which is at best conceptually engaging, but too often slides into tedious melodrama about heterosexual family life on the run (and bad wigs). It does, however, offer an almost perfect metaphor for the book-publishing industry. The Green Zone is that precarious landscape occupied by Big Publishing, and especially senior management and their police force (literary agents) who are still well compensated to usher in and manage the labor (authors). The alien overlord is Amazon (drones), which not only takes a big percentage of a book’s profits, but also dictates the operations of its colony.

Big Publishing is too tethered to Green Zone amenities to make any effort to leave or revolt; instead, in a state of collective denial, they try to please their overlords with “guaranteed revenue” (celebrity memoirs! sequels!), a wellspring that, however deep, can provide for only so long. Increasingly risk averse, they are incapable of publishing books that reflect the growing diversity of the population (in pretty much whatever way you want to define it) and make survival for “midlist” writers more and more difficult. (This has been happening for decades.)

That Big Publishing remains conservative and homogeneous — and viewed with increasing ambivalence and disdain by the larger population — should not be surprising or contentious; axiomatic in antitrust law is the idea that a reduction in market participants, whether a result of competition, attrition, or consolidation, correlates with a reduction in consumer choice. We’ve seen this across any number of industries in our society, including airlines, automobiles, banks, pharmaceuticals, newspapers, and commercial publishing, where somehow Penguin Random House isn’t the punchline to a joke.

Then there’s Amazon. If you talk to your overworked/underpaid friends who work in the trenches of Big Publishing, you’ll be keenly aware that no decision — from “content” to book covers to publication schedules to sales/marketing strategies — gets made without considering the actual or looming impact of the alien overlord/distributor. If Amazon is “unhappy” about anything, or if the perception of unhappiness is wielded like a dictatorial cudgel, the publisher will scurry to find a solution. The message — and the reality — from Amazon is: Make Us Happy or Die Trying.

Whether and how the demise of Big Publishing “matters” is a more subjective question. My own experience with Big Publishing is mixed. As a reader, my bookshelves (real and virtual) have a mix of titles by Big Publishing and independents. As a writer, I published my first novel in 2010 with Crown, an imprint of Random House. Based on BookScan, it has probably to date sold between 5000–6000 copies in hardback, paperback, and Kindle/ebook formats. (Exact numbers are very difficult to come by, and I’ve never seen a royalty statement.)

Like every author who gets signed by Big Publishing, I had an agent. In 2007, Crown bought the manuscript, paying out an advance in the very low (but still very high) “six figures,” fifteen percent of which went to my agent, and the rest to yours truly in three installments: signing, submission, and publication. (Around forty percent went to the IRS, also.) Though an outlandish amount of money to pay for a debut novel by someone best known for posting photographs of “hot gay statues” on my blog, Big Publishing still regularly/perplexingly doles out far more for debut novelists they hope will make it “big,” despite the fact that almost nobody ever does.

After this first novel finally published, to some acclaim and some derision, I was still excited enough that, when, two years later, Crown decided not to exercise their option on a second novel, I also felt like a failure. There were many reasons why the relationship fell apart. Sales — though not horrible for a first “literary” novel — were undoubtedly a factor, although nobody ever said so. Also problematic (although again, nobody ever said it, at least in so many words) was the subject matter of the book/s. My first novel was definitely “a risk” given that it was not only “gay” in thematic and sexually explicit senses, but also featured a primary character who was HIV positive, as well as opera, incest, a magic longevity potion, and — yes — a dying cat.

While my second novel could also be described without gay-pigeonholing it — specifically, it deals with faith or “faith,” or what we’re supposed to “believe in” if we don’t buy into traditional monotheistic religions/capitalism but find atheism too depressing — it’s also more “stridently gay” than the first one. There’s an all-gay, underground operation whose members are trying to contact a race of immortal beings/gods who may or may not be returning to the society they once ruled. There’s a subplot involving a semi-professional lesbian bowling league.

I mean, it’s obviously aWeSOmE and you should read it, but it would have been much more difficult to “market around” what the book is actually about, especially back in 2013, when people had a harder time admitting that our society is a train wreck for pretty much anyone who’s not rich, straight, white, and male. The plot also did not — as my editor put it in the coded bigotry of marketing — appeal to Crown’s “core demographic.” At a meeting with the editor and a new publisher, who had been installed during a regime change, the publisher expressed concern about avoiding a “sophomore slump” like (her examples) Zadie Smith or Curtis Sittenfeld. I heard these words and stared out the glass windows at the glittering, midtown skyline: somehow, I had ended up in a satirical movie about Big Publishing.

We went back and forth for about eighteen months (note: don’t ever do this without a contract), as I attempted to address vague directives from the editor: “Can we do something to make [this character] more compelling?” I finally turned in a “major rewrite,” which was followed by six months of radio silence: Crown wasn’t saying yes, but they also refused to say no (and never did, putting me into a kind of Big Publishing purgatory). I finally admitted that I needed to escape. Knowing my agent’s hands were tied by Crown’s refusal to commit/not commit, and not wanting to “sneak around” with other agents, I left him. I went through the motions of querying a few others, but it quickly became apparent that my days in the Green Zone were over. As one agent put it to me, “You’re not even a debut novelist anymore.”

Time passed and the world did not end. I stopped worrying about a “career” writing novels. I don’t need a career: I already have one that (thank God) has nothing to do with writing fiction. For me, writing is an avocation on the order of gardening or making paper airplanes. I write because it offers the chance to escape for a few hours each week into a dream world of my own making. I would love to have another big, fat advance (who wouldn’t), but I’m better suited to an independent. For small presses, existence is not divorced from the reality of Amazon, but — as my publisher has done — they can afford to take risks that their oligopolistic peers will not. They are the insurgents.

In my case, with no agent or “representation,” I sent the manuscript to the publishing director, who I knew in an around-the-office and (later) Facebook kind of way from a previous job (in academic publishing). After he moved to San Francisco and — with some friends — started Fiction Advocate, I bought a few of their books and was impressed: with each new title, they seemed to be getting more polished (no surprise, given that they all have experience in traditional publishing). There are hundreds and possibly thousands of small publishers around the country; reading their books is the best way to get to know them.

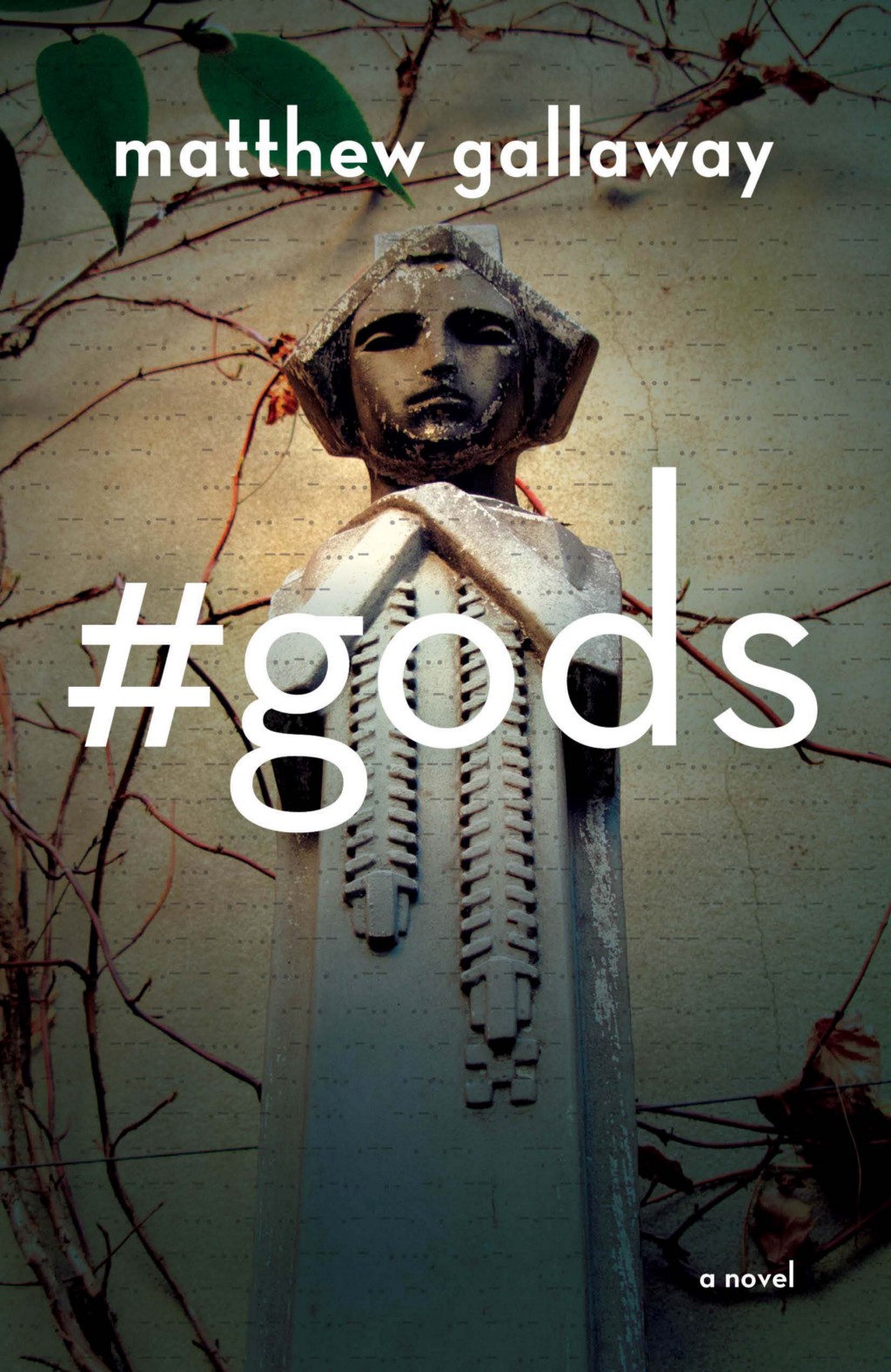

The publisher liked my new manuscript and extended me an offer; we negotiated a contract in two very low-key e-mail exchanges. The editing and production processes were more “collaborative.” My publisher didn’t ask for edits to appease an imaginary book club. He didn’t roll his eyes when I suggested using one of my photographs for the book’s cover. He also didn’t take three years to publish the book. The process was still “professional” — there was a copyeditor and a designer and proofreader — but was a lot more fun. Sales figures are still TBD, but with lower expectations, there’s less pressure. I’m trying not to be too annoying on Facebook and Twitter, but I’m doing what I can to promote the book. Like any writer, I want people to read.

At the same time, I’ve learned to think about publishing a book — any book — as something like winning a gold medal . . . in archery. Put it in your drawer, take it out to admire once in a while, and get back to the rest of your life. If things unravel with a publisher or an agent, don’t worry too much. If it makes you happy, keep writing. Or don’t. Nobody cares! And if, like me, you’re lucky enough to find a new publisher as a non-debut novelist, even if it’s a very small one that can’t afford to pay you ten cents for the manuscript, remember to be very grateful, because they’re demonstrating a kind of faith and resistance you once thought was lost.

Matthew Gallaway’s new novel #gods can be ordered here.