Did Amway Create the Gig Economy?

“Once again, it is the Law of Compensation.”

“This is just Amway and Avon all over again. But idiot me, I still drive.”

Amway is a fifty-eight year old multi-level marketing (MLM) company that sells soap, laundry detergent, and health supplements. Last year, it began insisting that it was part of the gig economy. Jim Ayres, head of business operations for Amway in North America, says direct selling isn’t just a gig, but one of the best gigs out there. “Take a look inside the ‘gig economy’ and what it means for YOU” shouts the Amway Twitter account. On their official blog, direct-selling is identified as a common type of gig economy job, right alongside ride-sharing and home-sharing.

Thus far, these efforts haven’t paid off with a seat at Code Conference or the Aspen Ideas Festival. The only people to echo Amway’s claims are gig economy workers themselves: search “Amway” on Uberpeople, a popular forum for Uber and other rideshare app drivers, and hundreds of threads pop up. “Lyft and uber is Amway on wheels,” wrote one user. “Uber is this generations Amway, without those annoying monthly checks for recruiting a superstar performer,” wrote another. “Funny you mention Amway. I wouldn’t be surprised if the two corporations merged. They seem to have many similarities,” wrote a third.

Amway was founded in 1959 by Jay Van Andel and Rich DeVos, father of Michigan gubernatorial candidate Dick DeVos and future father in-law of education secretary Betsy DeVos. The two friends had been involved in several business ventures before becoming independent distributors for Nutrilite, a vitamin supplement developed in the 1930s. Dismayed by how Nutrilite sellers competed amongst themselves for clients, DeVos and Van Andel formed Amway, which would use a more sophisticated multi-level marketing scheme to sell Nutrilite supplements, detergent, nail polish, and other household items (later, they would buy Nutrilite from its former distributor, Mytinger and Casselberry, Inc.). In his 1993 book, Compassionate Capitalism, DeVos notes that Amway was founded the same week Fidel Castro overthrew Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. “It has been just thirty-four years since Castro took over Cuba promising prosperity in reform,” he wrote. “Today most Cubans live in poverty and despair…. Amway, on the other hand, became a four-billion-dollar corporation.”

To say those billions of dollars were earned by selling soap is an understatement; Amway’s success hinges on its byzantine marketing structure. You can buy products directly from Amway’s website, but most products are sold through its distributors — independent contractors who buy their stock from the company or from the person who brought them into the organization, known as their “upline” distributor. Today, distributors can sell their wares at whatever price they see fit, though this was not always the case (price restrictions were key to the Federal Trade Commission’s complaint against Amway). Amway has always noted that signing up distributors carries no monetary bonus, and that signing up distributors is not necessary to earn a profit with Amway. Substantial income, however, requires a significant “downline” of distributors.

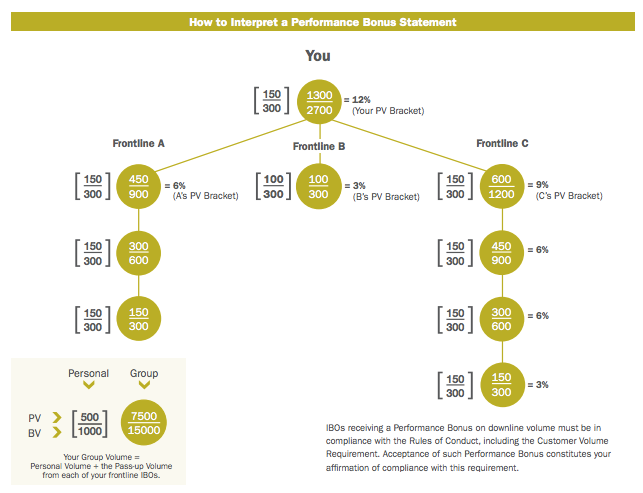

Each Amway product has a Point Value and a Business Value, the latter of which is a fixed dollar amount. Even if you manage to sell Amway’s detergent for $1000 a pop, its business value will remain the same. Every month, distributors add up their point values, then see where it fits into the performance bonus schedule: the higher your point value (PV), the higher the percentage of the business value you receive as a bonus. Larger bonuses can be earned by signing up other distributors, or adding them to your “downline”; in calculating your monthly PV, you add up the PV of your downline distributors along with your own. If your eyes are glazing over, just listen to Sammy Hall’s “Circles, Crazy Circles,” a song about the diagrams shown to prospectives; according to former distributor Stephen Butterfield, Hall’s songs were regularly played at Amway rallies.

Since the big bucks almost always require a large downline, and distributors on that downline can only earn the big bucks if they develop downlines of their own, Amway has been accused of being a pyramid scheme, since its distributors would presumably run out of people to recruit. But in 1979, the Federal Trade Commission found that though Amway’s price fixing “would probably violate the Sherman Act,” its organization was technically legal (in an initial decision, an administrative law judge reasoned that in areas where population growth outpaced distributor growth, there was little reason to worry). As the New York Times business columnist Joe Nocera observed in 2015, this ruling allowed later MLM firms, such as Herbalife, to legitimize themselves by modeling their business after Amway.

At first glance, the company couldn’t be more different from Uber. Uber is cosmopolitan, global, and hedonistic to a fault. Amway is short for American Way — DeVos and Van Andel are so studiously Midwestern that they commissioned Norman Rockwell to draw their portraits. But if the gig economy is just “ordinary tasks, but codified and structured such that a billion-dollar company can be built on top of them,” then the companies are in the same boat. As a Bloomberg reporter observed in a recent article about Avon, a similar multi-level marketing company, “selling jewelry and make-up on the side isn’t really so different from driving an Uber.” And just as Travis Kalanick broadcasted his affinity for Ayn Rand, these two Calvinists also embraced free-market capitalism to a degree that would make Max Weber weep. “Life, like it or not, is a harsh regimen in which rewards are contingent on behavior,” DeVos wrote in his 1975 book, Believe! “That is not an artifact of capitalism; it is a rule of nature itself.”

Performance-based bonuses aren’t unusual, but what makes Amway’s structure of bonuses distinct is the lack of any base pay or safety net (DeVos’s comments on the “rule of nature” come after a critique of job security and across-the-board wage increases). Amway’s distributors only earn when they turn a sale, with no provisions for effort or time invested in the company. Though Uber puts on a friendlier face, the performance-based model is the same. According to Uber’s website, “You can drive and earn as much as you want. And, the more you drive, the more you’ll make.” In April, New York Times labor reporter Noam Scheiber contended that Uber’s faster pickup times meant drivers were spending more time idling without passengers — time for which they receive no compensation. Uber disputed that claim.

In both companies, distributors are responsible for any costs they incur while doing their job, which may drastically reduce earnings. In his autobiography, Amway co-founder Jay Van Andel sneered at the people who lose money through Amway, blaming it on their purchase of expensive video equipment to help sell goods (a nearly identical anecdote can be found in 1985’s Promises to Keep, a laudatory book about the company written by frequent Amway chronicler Charles Paul Conn). After the Super Bowl this year, Travis Kalanick infamously yelled at a driver who claimed he had lost $97,000 driving for Uber, saying that “some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit.”

The idea that employers are not responsible for their employees predates Uber or Amway. But Amway pioneered a way to package that arms-length relationship between a company and its workers, and the way they sold their vision is nearly identical to the way Uber and other gig economy companies pitch themselves.

The pitch for driving for Uber is clear: “You like the idea of choosing your own hours, being your own boss, and making great money with your car.” “With Uber, you get to set your own schedule and you only have to drive when it works for you. There’s no office, no boss, and you’re in charge.” The nature of that appeal is familiar to anyone involved with Amway. “Income opportunity, flexibility in hours and location, and independence from an employer, all with low barriers to entry,” a 2016 company blog post read. “These are benefits that Amway has been offering for decades, long before anyone ever uttered the term ‘gig economy.’”

Though Avon may have beat them to the punch, there’s a surprising amount of truth to that claim. Amway distributors, DeVos tells us in Believe! are “working for themselves.” A ’70s Amway guide for distributors urged them to tell prospects that “Amway can offer you an opportunity for true independence. Freedom from time clocks…. [F]reedom from allowing someone else to decide your financial progress.”

These advantages are stressed most of all, however, by Charles Paul Conn, a freelance writer and professor with a peculiar relationship to the company. Conn co-authored DeVos’s Believe! in 1975, then wrote five purportedly neutral books about Amway (The Possible Dream in 1977, The Winner’s Circle in 1979, An Uncommon Freedom in 1982, Promises to Keep in 1985, and The Dream that Will Not Die in 1996). These books occasionally contained disclosures about Conn’s relationship with DeVos and usually contained sentences like “the money is there to be earned, and many people are earning lots of it” (from The Possible Dream). “I guess the book does lack a counterpoint,” Conn later admitted.

In An Uncommon Freedom, Conn writes of how Amway distributors might be granted “freedom from the alarm clock, the commuter-bus schedule, the nine-to-five drudge.” Earn when you want, chill when you want, Uber promised in 2016, but Conn was making similar promises decades before: “Much of the appeal of the system, as opposed to other more conventional part-time jobs, is that the distributors have the choice of working as much or as little as they like, when they like, and be paid accordingly,” he muses in The Winner’s Circle. In a 1980 commercial, part-time distributor Gordie Howe made the same promises about Amway: it’s a flexible part-time job that’ll earn you extra income. Incidentally, Howe’s other promise — that you’ll “meet new people” — is also made by Uber, which often highlights the fun people you’ll meet on the job.

Both companies have promised great wealth. During rallies in the 1970s, DeVos would tell audiences that they should start “thinking in terms of making $100,000 a year because you can do it and you ought to think that way.” Uber notoriously stated that the median driver in New York made over $90,000 a year. Lower earnings, both companies explained, were due to contractors who voluntarily worked part-time. In a 2015 speech, then-spokesman David Plouffe stressed that many of Uber’s workers fell into this role. “It’s just driving an hour or two a day, here or there, to help pay the bills,” he said. Van Andel, in his autobiography, explained that many distributors saw Amway as “solely a part-time occupation — something to bring in a little extra cash every month.”

But the most curious feature of Amway and Uber’s pitches to prospective users is that they create small businesses. In Believe!, DeVos applauds the “two hundred thousand independent Amway distributors working for themselves.” Summing up Amway’s affairs in 1993’s Compassionate Capitalism, he boasted that there were “more than two million independent distributors who own their own businesses.” In An Uncommon Freedom, Conn describes Amway members in the exact same terms, calling them “independent distributors who own their own business.” Business lobbyist Richard L. Lesher, who headed the U.S. Chamber of Commerce for 21 years, echoed this in 1997, writing “the small business revolution is here to stay… Amway is in the vanguard of that revolution.” (If Lesher’s devotion to Amway wasn’t clear enough, those words appeared in his introduction to “Amway: The True Story of the Company That Transformed the Lives of Millions,” an authorized history of the company written by Wilbur Lucius Cross).

Uber has harped on this point with even greater vigor. In a 2012 interview with Washingtonian, Travis Kalanick stated that “we’re connecting riders and drivers. They are not our cars and not our drivers. They have their own companies, or they’re freelancers.” A year later, Kalanick wrote a blog post where he called Uber’s drivers “transportation entrepreneurs.” “As an Uber driver-partner, you ARE an entrepreneur!” says one driver in an interview featured on Uber’s website. “Now I feel like I am a small entrepreneur,” laughs another driver in an Uber ad. Uber’s commitment to the “entrepreneur” label is reflected in its many legal actions, some of which seek to stop drivers from being classified as employees and some of which simply distance the company from its contractors: when a six-year-old was killed by an Uber driver in 2013, Uber denied any liability because the driver was off-duty. Later, the company settled for an undisclosed amount.

But even ignoring the absurdity of billion-dollar companies claiming they’re really in the business of making businesses, “becoming an entrepreneur” hardly describes either the Uber or the Amway experience, since both companies sharply restrict how their “entrepreneurs” can do business. The app, in Uber’s case, does not allow drivers to set their own rates, and may shut off access to passengers if their rating drops below a certain level. Amway’s rules of conduct forbid distributors from selling to anyone they did not personally sponsor or selling Amway products in any kind of retail establishment.

Both Uber and Amway’s marketing schemes have led to actions by the Federal Trade Commission. In 1979, though the FTC declared that Amway was not a pyramid scheme, they did order the company to stop misrepresenting the amount its distributors can make. Central to the FTC’s judgment was Amway’s frequent use of $200 as a typical monthly business value; in 1973–74, the actual average was $33. As a result of the judgment, Amway must prominently disclose the amount made by average distributors (according to a September 2016 document, the average monthly gross income was $183). In 1986, the company had to pay $100,000 for violating this order.

Uber, meanwhile, paid $20 million to the FTC in 2017 over misrepresentations of the amounts its drivers could make; the complaint cited Craigslist advertisements that promised earnings far above the median amount earned by drivers, along with the infamous assertion that the median income was over $90,000 a year in New York and $74,000 per year in San Francisco. In The Possible Dream, Conn claims that the FTC has filed complaints against “just about every other American company that has managed to show a profit during the past few years.” This defense, meager as it may be, would not work in Uber’s case.

“I think Uber will be regarded in a similar way to Amway in the future,” one Uberpeople user wrote in 2016. But the question of how Amway is regarded depends on whom you ask. While never losing its punchline status in some circles, Amway became one of the most well-connected companies in American history. Conn claims that in 1965, then-Congressman Gerald Ford read DeVos’s “Selling America” speech into the Congressional Record. In 1973, Ford attended the opening of Amway’s Center of Free Enterprise. As president, he invited DeVos and Van Andel to the White House. Jesse Helms and Ronald Reagan spoke at Amway rallies in the 1970s (George H.W. Bush would later be paid $100,000 for an Amway speech).

In 1981, President Reagan attended the opening of the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, along with Nancy Reagan; Gerald and Betty Ford; George and Barbara Bush; Henry and Nancy Kissinger; Lady Bird Johnson; Secretary of State Alexander Haig; and Pierre Trudeau. When Haig left the White House, he began consulting for Amway.

In Compassionate Capitalism, DeVos offhandedly mentions that he served on Reagan’s AIDS Commission (in Promises to Keep, Conn wrote that “gay rights… are still not popular causes at an Amway rally,” and during his time on the Commission, DeVos said that homosexuals wanted to “capture the agenda”). Ford, Haig, and Reagan’s surgeon general C. Everett Koop all wrote praise-filled blurbs for Compassionate Capitalism. Van Andel and DeVos donated $2 million each to the Progress for America Voter Fund, a 527 committee supporting George W. Bush’s reelection campaign. And as Politico noted in January, Rich’s son Dick DeVos used the family fortune to reshape Michigan politics following a failed run for governor in 2006; his wife, Betsy, is now the Secretary of Education (in Believe!, her father-in-law writes “…the next year I went to a public school. I didn’t like it there.)

In his 1975 book, DeVos railed against communism, affirmative action, Ralph Nader, and creeping atheism: he notes that there is a “difference between the company of Christian people and those who have no faith” and that “this country was built on a religious heritage and we’d better get back to it.” When he wrote Compassionate Capitalism 18 years later, he adopted a warmer tone and narrowed the subject matter: aside from some puzzling asides on evolution, the book largely focuses on economic issues.

DeVos’s sunnier demeanor makes sense; on this issue, he had won. Even if Amway’s business model was suspected, the company-contractor relationship became accepted. The idea that a company’s workforce could be made almost entirely out of non-organized, non-salaried workers who are entirely responsible for their own supplies, health insurance, and other expenses was alien when Amway began in 1959. Today, those ideas are said to be the future of work.

Uber’s recent turbulence — the sexual harassment disclosures, the dalliance with the Trump administration, the file on a rape victim that an exec carried around for a year — may well sink the company — it has already forced founder Travis Kalanick to step down. But that collapse would not end the business of ride-sharing; competitors like Lyft or Curb would swiftly move in. The degree to which DeVos’s ideas have been accepted can be gauged by the number of Obama and Clinton acolytes who have left to work for the gig economy, as Nathan Heller recently noted in The New Yorker. Most prominent among them is David Plouffe, who joined Uber in 2014 and left this January. Plouffe, who ran Obama’s 2008 campaign, should be diametrically opposed to the far-right DeVos (in 1981, DeVos said that critics of Reagan had a “limited mentality” and had been “trying to destroy our country for some time.)”

Here is what DeVos wrote about wages and benefits in 1975:

“Job security, if it means that a man cannot be fired no matter how poorly he performs, can be just another way of avoiding accountability. Automatic, across-the-board pay increases often provide for workers to be rewarded equally, regardless of their competence, and thus nullify the usefulness of meaningful evaluation.”

And here is what Plouffe said in 2015, when Ezra Klein asked him if Uber was profiting from wage stagnation in America:

“There’s no doubt if people were getting 10% raises every year, you know, maybe they’d feel a little less need. But that’s not reality.”

For DeVos, the benefits that unions fought for constitute a moral crime. For Plouffe, they’re just not realistic. There is a world of difference between those philosophies, but they’ve arrived at the same result: gig work. And if these two agree, hey — something must be going right. As DeVos writes in Compassionate Capitalism, citing two of his favorite thinkers: “The apostle Paul and the dog Snoopy are both getting at the same idea. Once again, it is the Law of Compensation: Do good! Work hard at it! And you shall be rewarded!”

Petey Menz is a writer in Connecticut. He can be reached via email.