Charm? Offensive!

Sarah Huckabee Sanders and the true grit of Southern women.

The Sean Spicer rise-and-fall narrative never interested me; the herald is dead, long live the herald. “We’ll Miss You, Sean Spicer,” read the headline atop a Sunday Times op-ed, with all the sincerity Charlie Brown’s pride would display if Lucy resigned from holding the football for the punt. After ticking through a rogue’s gallery of potential replacements, the piece concluded “none of them could possibly convey the combination of chutzpah and shame” projected by Spicer.

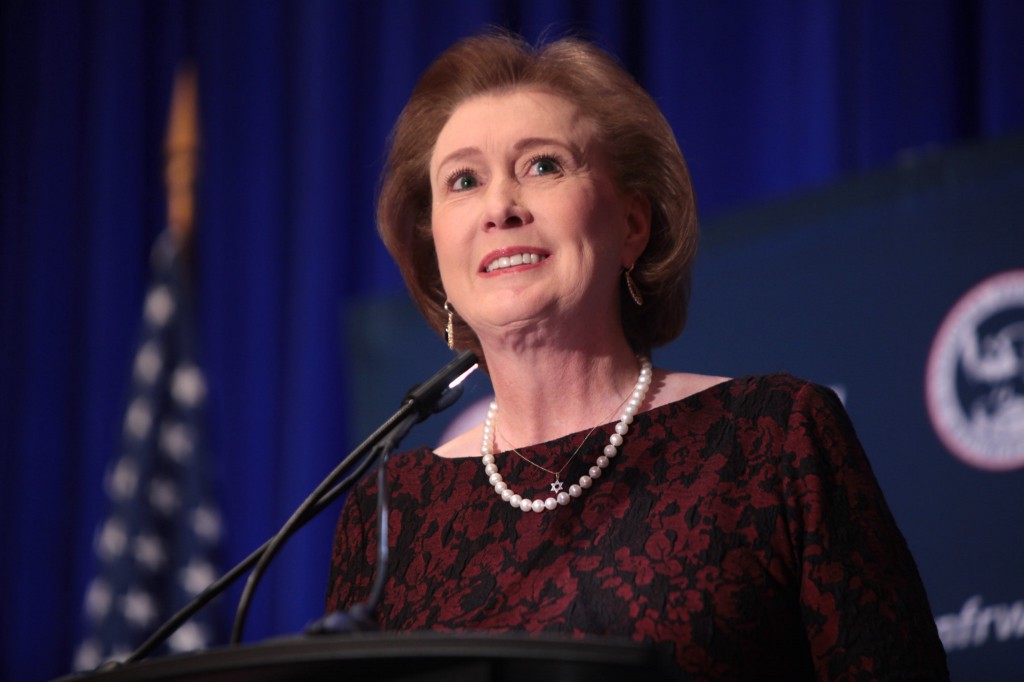

“Saturday Night Live” divined months ago that Spicer’s days were numbered, and that Sarah Huckabee Sanders waited gleefully in the wings. Well, as gleefully as she is able: The op-ed also opined Sanders “has all the sparkle and charm of the airline call center employee who tells you there’s no way you can get on a flight to Chicago until at least Wednesday.” Spicer gets “chutzpah and shame,” Sanders gets “sparkle and charm,” spritzed ironically. Like Trump’s Presidential Advisory Commission on Election Integrity, I’d demand to see the receipts. At the very least Sanders deserves a more accurate alloy. Flint and antipathy, maybe.

I admit I’m something of a Sanders apologist. Not for her politics — more as a corrective against the suggestion she should come off as a helpful airline employee. Dee Dee Myers was no Braniff Airways holdover, dispensing coffee in Pucci pink. The line on Sanders, of course, is that she is her father’s daughter. “For those of you who don’t know me yet, my father is Mike Huckabee,” Aidy Bryant grunted, Sling Blade-style, while debuting her Sanders impersonation on “SNL.” She added, almost as an afterthought, “and my mother is a big Southern hamburger.”

Setting aside the fact that a “big hamburger” is no more Southern than a big chicken schnitzel, I will even be generous and suggest that whoever wrote that line did not have in mind Sanders’s actual mother. But I do. Not as a righteous abstraction, but as the real Janet Huckabee, former first lady of Arkansas.

I covered state government there occasionally, and have spent time observing and writing about Mike Huckabee, including a surreal Saturday afternoon in 2010 hanging around the greenroom of “Huckabee,” the former governor and occasional presidential candidate’s erstwhile Fox News talk show. I was there to try and suss out whether Huckabee planned a second run at the Republican nomination, for Arkansas Life magazine, a supplement of The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. The show’s host was not long past officiating his daughter’s wedding to Bryan Sanders, a political operative Huckabee’s campaign had inherited from the failed one of Sam Brownback. Guests for that day’s taping included a love child of Fidel Castro’s, along with Newt and Callista Gingrich (who does seem like a Braniff Airways holdover.)

The patter of the warm-up comedian was of a piece with Huckabee’s Dad jokes: “Did you hear about the fire at the circus? It was in tents.” “SNL” got it backwards about Sarah Huckabee Sanders. She is her mother’s daughter; her father is the big Southern afterthought. Janet Huckabee’s eye roll at that circus-fire joke would have be so strenuous even Sarah would feel it, likely dropping a false eyelash. Mike Huckabee had already experienced the call to ministry by the time he met his future wife, when they were both students at Hope High School. As Slate once noted in an installment of its First Mates series, the future Janet Huckabee would attend Mike’s after-school prayer meetings, “if she didn’t have basketball practice.” Years later, when Sarah Huckabee Sanders was named to Time’s “40 Under 40” list of ascendant politicos, she claimed to have little time for blog-reading, between being a newlywed, and managing her fantasy football team.

Her mother had not been a first lady who, to borrow a notorious quote from another, “stayed home, baked cookies and had teas.” She drove nails into Habitat for Humanity homes — and not just for photo ops. “I will take non-physical risks, such as running for office,” Mike Huckabee wrote in his book Character Makes a Difference. “Janet will take physical risks — climbing cliffs, parasailing, racing cars or stalking bears.”

When a young middleweight fighter named Jermain Taylor emerged from a makeshift boxing gym in Little Rock to the national spotlight, the Arkansas first lady took up his cause and became an avid fan of the sport. At a blustery press conference before a 2006 professional bout, The New York Daily News documented Janet Huckabee trying to get in the head of Taylor’s opponent. “Kassim, you’re a dead duck,” she taunted, addressing the boxer Kassim Ouma. In his native Uganda, Ouma was kidnapped at the age of six and forced to serve in the National Resistance Army until he was 19. The Daily News described the former child soldier smiling politely at Janet Huckabee’s warning, as one might after a Dad joke.

When most writers were filing their “Sean Spicer, we hardly knew ye” pieces, I was reading a tribute to a woman’s voice at once:

naive, didactic, hard-headed…completely lacking in self-consciousness…and unintentionally hilarious,” one in which “shootings, stabbings, and public hangings are recounted frankly and flatly, and often with rather less warmth than…political and personal opinions upon which [she] digresses.

This was novelist Donna Tartt, writing in an Overlook Press edition afterword about Mattie Ross, the vengeance-seeking heroine and narrator of Charles Portis’ True Grit, just 14 when we meet her. But to my ear it could just as easily have been a Twitter thread following Sarah Huckabee Sanders’s first day on the new job, shooting from the hip in her double-action southwest Arkansas drawl. Some readers have been inclined to see Mattie as a female Huck Finn — that is, a national treasure. But how anchored is that affinity to the preference she remain an eternal tween? “A woman with brains and a frank tongue…is at some disadvantage,” Mattie remarks at the end of the novel, when we understand it’s all been rueful memory, recited sentiment-free by a spinster. “Mattie is a much harder customer than careless, sweet-tempered Huck [Finn],” Tartt decides.

Last spring when Joan Didion published South and West, the reviews promised the book’s data dump of unused notes from a Gulf Coast reporting trip in 1970 would take us slouching toward Baton Rouge, for a sense we’d been present at the birth of the Trump voter. Of America’s white women who voted in 2016’s presidential election, 53 percent of them cast their ballots for Donald Trump; presumably, Janet and Sarah Huckabee were two of them. Didion, growing up in Republican Southern California, had been a self-proclaimed Goldwater girl. Flying to her hometown with Michiko Kakutani she once gazed out the airplane window and mused, “anybody who talks about California hedonism has never spent a Christmas in Sacramento.” Kakutani understood she was talking about understanding conservatism.

Didion also had made an enemy of Nancy Reagan; I figured she might have met and deconstructed some unreconstructed proto-Huckabees, so South and West I went. But Didion seems to have only encountered lovelorn manicurists, ladies who luncheon but have no passports, and those who look askance while she swims in a bikini in the Howard Johnson’s pool. This seems to bear out her own self-criticism, that “all the reporting tricks I had ever known atrophied in the South.”

I’ve read enough of Didion’s self-criticism to know that she never speaks highly of her own reporting tricks, and enough of her fiction to know she does not much gravitate toward women who clearly know their own minds. The only female figure in South and West who does seem to know hers is one of the rare professional women Didion meets, a physician taking time off to renovate her house. I couldn’t help but think of Janet Huckabee pounding nails, or her daughter shooting daggers with her eyes at Jim Acosta.

“In certain ways she seemed to have been affected by the great leap she had taken out of her time and place,” Didion writes. “In order to be her own woman she had found it necessary to vehemently reject many of the things which traditionally give women pleasure, cooking…any vanity about her own appearance, any interest in having her house reflect her own tastes.” In other words, were she an airline call center employee, she’d have been one of those emotionally stunted ones, with no personal investment in whether or not you make it to Chicago.

Were she a White House press secretary she might even ban cameras, or bark non-answers. You can resent Sanders’s caginess because it represents an atrophying of the First Amendment, but I cannot help but admire the frontier self-preservation I see at work there. “I would not put a thief in my mouth to steal my brains,” Mattie says in True Grit, declining alcohol. To Sanders that’s what news cameras represent, a thief in her mouth, creeping up on her brains. You could argue she’s in the wrong line of work, then, but I say we won’t soon be in a position to backhand-compliment her chutzpah and shame as she skulks off to the private sector. I’d bet a big Southern hamburger dinner on it.

Kyle Brazzel lives in Brooklyn but still spends time in Arkansas. His accurate alloy would be sloth and Ro-Tel.