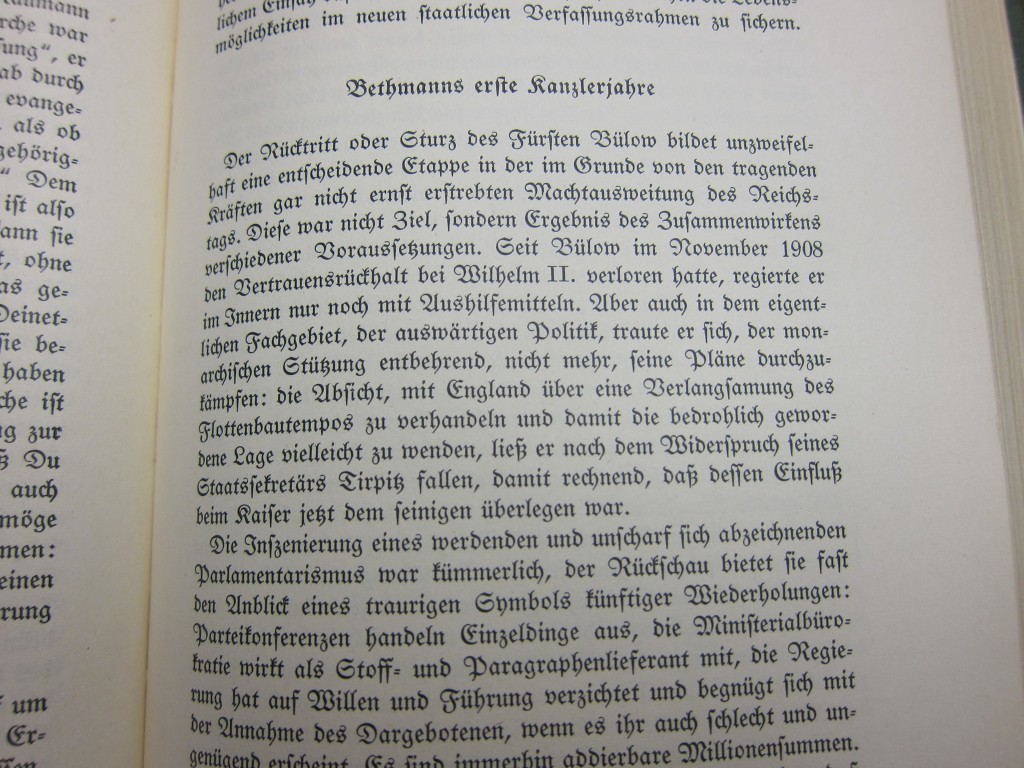

ẞ is for Nothing (SCHEIẞE!!!)

Deutschland über us.

While America was busy celebrating its 241st anniversary of independence from the British by committing a kick-ass new patriotic song to the canon (also maybe starting World War III), our no-longer-friends in Germany did not even have the chance to get us with any truly good burns about our sad state of affairs, because they were too busy reeling — reeling — from the latest attack on their traditional values.

No, I’m not talking about “marriage for all” (as Germans call it, and which was legalized in a parliamentary vote last Friday). What’s currently gripping Germany is even more controversial. I’m talking about a change that shakes the very notion of Germanness to its Kern. I’m talking, of course, about the new letter that was just officially added to the standard German alphabet.

That monstrous grapheme you see above is ẞ, the großes Eszett (GROSS-us ESS-tset), or capital ß, the letter best known to English-speakers worldwide as that big-B thing.

Yes, in its more ubiquitous form, ß does vaguely resemble a stylized upper-case Roman “B,” but you will have to trust me that it is pronounced like the double “s” sound at the end of English words like kiss and hiss.

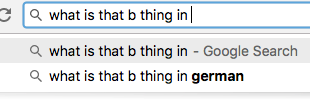

The most famous appearance of the ß in the non-German-speaking world is in the word Scheiße (SHY-suh), or shit, which was made even more famous in 2011 when Lady Gaga used it as a song title, along with several bars of nonsense-gibberish-German on repeat that people kept asking me to “translate” for them.

To this day, if you try to Google that song, autocomplete offers Scheibe (SHY-buh), which means “slab.”

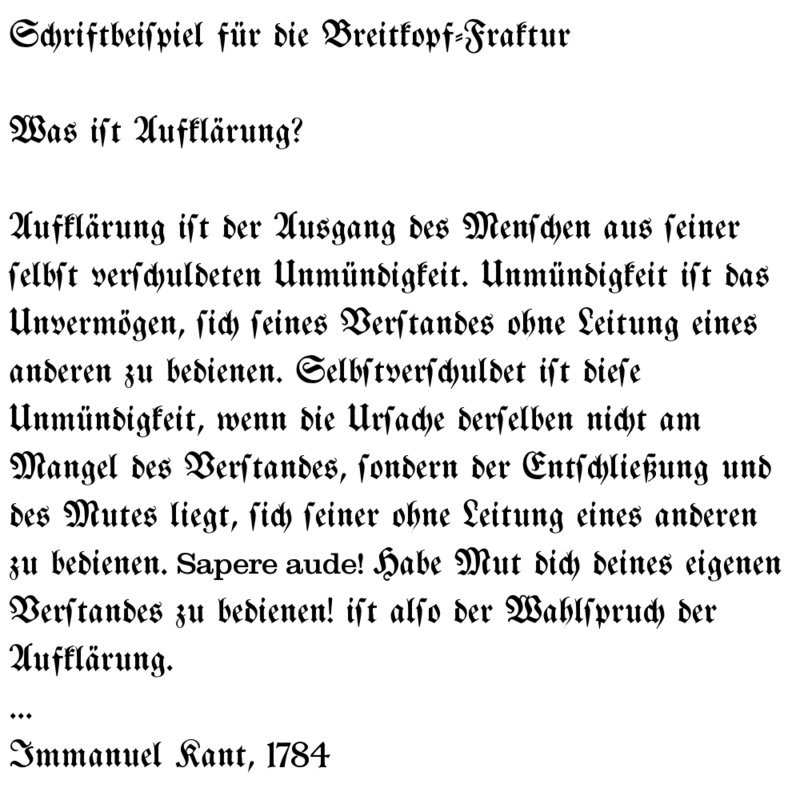

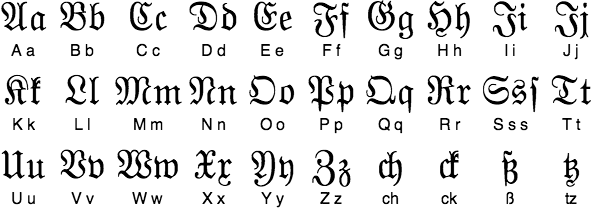

Though the ß is pronounced like a double s (and indeed, in Switzerland is replaced by one), the Eszett gets its name from the words for S and Z, and its unique shape from the way those letters used to look in the unholy German typeface known as Fraktur (frok-TOUR).

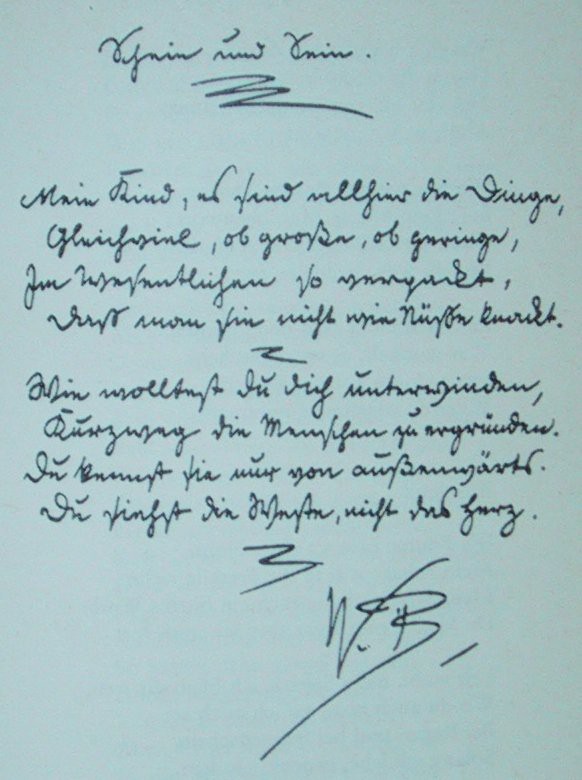

If you think that looks hard to read, by the way, check out what German cursive script used to look like:

Fraktur came into use in the sixteenth century, and most German documents set in type used it until the early twentieth. You may think of it as “the Nazi font,” but you’d only be half-right. At the beginning of the Third Reich, Hitler did prefer Fraktur, excoriating Latin fonts as the stuff of the Jew-run media — but then, in 1941, the NSDAP abruptly changed course, decided Fraktur was too Jewish after all, and banned it. (Some people think that this was actually a pragmatic choice; after Germany won the war and took over the world, it would be important for their decrees to be legible to all of their new subjects.)

Anyway, Fraktur had two versions of the small letter “s,” the one that looks a lot like that thing every middle schooler in 1996 covered everything with, which was used when an “s” ended a word. And then, there was the “s” used in the middle of a word, which looks way the fuck too much like a modern “f” and made for some interesting confusions in grad school, when I insisted it was “fine” to read assignments in Fraktur because “of course” I could do that:

When this second “s” appeared next to a Fraktur “z,” typesetters combined them into one character. And since the German “z” is pronounced like an English TS sound, putting one after an “s” in the middle or end of a word effectively created the sound of a sharp or double-S. (ME LOVE ORTHOGRAPHY but this is super-oversimplified, K? Don’t hate.)

Aaanyway, the long and short vowel of it is this: Because of the narrow circumstances of its birth, the ß is a character that a) is unique to the German language, and b) has never technically needed an officially-recognized capital version. UNTIL NOW.

Until last month, the German Council of Correct Spelling (the Rechtschreibrat, or WRECKED-shryb-rott, a thing that one hundred percent exists) didn’t see fit to include the “big ß” in the language’s voluminous official standard regulations. This is largely because the rules of German spelling dictate that the ß only appears at the end of a syllable.

The Logik would follow, then, that since one will never use it to begin a word, one will never need a big version in any official capacity. However, as this fascinating piece in the Süddetusche Zeitung points out — a newspaper that, by the way, printed an entire article about the capital ß without being able to print the letter itself, because they don’t have it standardized in their house font yet — there are actually times in which the ẞ is called for, aside from the extremely important work of writing SCHEIẞE.

Twitter poll for Germans: Before the ẞ entered official orthography, how did you spell “Scheiße” in all caps?

You see, on passports and in other official correspondence where names and other important words are in all caps, there needs to be a way to differentiate between a word that contains an ß and one that contains SS, since those are, technically, two different words. “People named Großmann and people named Grossmann won’t have to have their names spelled identically on their passports anymore,” explains the Süddeutsche, lending credence to my hypothesis that all people named Großmann and Grossmann are mortal enemies with each other.

So you’d think that this appeal to accuracy, in both naming and cursing (two things Germans hold dear), would be enough to universally welcome the ẞ. But you are wrong. For one thing, people hate the way it looks — hulking, pointy, bold-looking even when it’s not in boldface. “On a bend that’s as wide as a 1960s-issue streetlamp,” says the Süddeutsche, “dangles a violent hook, which looks like it could tip the whole thing over at a moment’s notice.” It is, in effect, “the SUV of letters.”

Add this, then, to the fact that the poor ß has had a tough go of it in recent decades. In 1996, Germany reformed its voluminous spelling rules to allegedly make it easier to follow them — and some 90 percent of those rule changes involved kicking the poor ß to the curb. (The other 10 percent involved removing commas, which gave undergraduate German majors all over the US license to never use a comma again, or, rather, to never start using one in the first place.) The biggest example of Verschlimmbessern (vur-SHLIMM-bess-urn, or making something worse by trying to make it better) was one particular result of the new rule that the ß could only be used after a long vowel or a dipthong.

Not only did this mean that in rare instances, a correctly spelled word could now have three S’s in a row — Flussschifffahrt, or “river boat trip,” which also contains three F’s in a row — but, as the Süddeutsche points out, the much-maligned difference between the subordinating conjunction that used to be spelled daß, which means “that” (as in, I know that you are not as good at German as you think you are), and the pronoun das, which also means “that” (but as in, Bring me the book that’s over there on the table that explains the rules of German correctly) was not simplified in the least. Under the new rules involving short stressed vowels, the conjunction became dass, but it still means “that,” and it still sounds exactly like the other das, which STILL MEANS “THAT.”

You know what? DAS IST TOTAL SCHEIẞE!!!!!

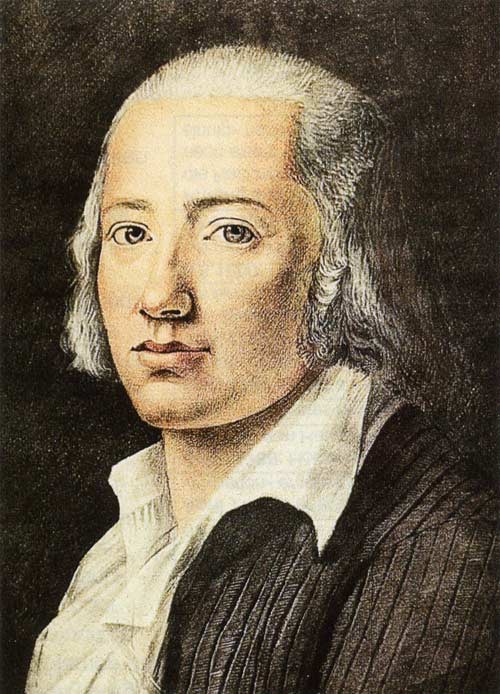

It is precisely these charming orthographic disputes that surely brought the novelist John Le Carré to his lifelong passion for German, which he condensed into a recent and elegant hagiography in the Guardian, one that urges us all to learn the dulcet vernacular of Heine and Hölderlin.

The latter poet, by the way, spent the final 36 years of his life in the throes of mental illness, having locked himself up in a tower on the banks of the Neckar river in 1806. There was plenty in Germany that was less humane back then (including the diagnosis of schizophrenics as “incurable”), but still: As Hölderlin gazed, in his anguish, at a boat as it floated past, the word that described its path was still spelled a far more reasonable way, Flußschiffahrt — and what’s more, there was not a hulking, tipping ẞ anywhere in sight.