We Should Ban The Word "Wanderlust" But It's Also The Only Word I Can Think Of To Describe Rimsky...

After dipping back into the Russian canon last week, it made sense to stay within the region, especially after friend of the column and #tbt queen Kristen Sales suggested I write an entry on Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. Rimsky-Korsakov! The ol’ R-K. I have to admit, Scheherazade was a relatively new work for me; my go-to R-K (this is the last time I’ll use this nickname) is Capriccio Espagnol which, like many pieces from my youth orchestra days, is both an old favorite as well as a source of pre-teen trauma. We’ll get there one day, maybe.

Context is essential in listening to Scheherazade: Rimsky-Korsakov was absolutely wild about what we now call “wanderlust.” He’d say he likes to travel on his dating profile. My guy was bonkers for being any place but Russia. Born a ways outside of Saint Petersburg to a family of great nobility, Rimsky-Korsakov spent his earliest years totally fucking obsessed with his older brother Voin, who was 22 years his senior. The reason for this obsession (admiration is probably the polite term, I guess) is that Voin was an expert navigator and explorer — an extremely cool job for a brother to have. For what it’s worth, my brother is “only” a teacher. When he was 12, Rimsky-Korsakov enrolled in the School for Mathematical and Navigational Sciences in Saint Petersburg with every intention of joining the Imperial Russian Navy upon his graduation.

While at school, Rimsky-Korsakov was enrolled in piano lessons at the behest of his older brother (a director at the school) in hopes that it would help him overcome… his… introversion? Oh, for sure, dude. Like the social activity of playing piano has ever helped anyone become more social. Mmhmm. His teacher for the bulk of that time was a Frenchman named Théodore Canille, who introduced Rimsky-Korsakov to Mily Balakirev, who then introduce him to César Cui and Modest Mussorgsky. All three of these guys were young composers in their twenties, which, okay, I guess learning piano did help Rimsky-Korsakov to make friends. They formed a little clique of pals who would meet up and talk about composition and music and play duets. Very cute, to be honest. (It’s worth noting these pals, along with Alexander Borodin joined together to create “The Five” a.k.a. “The Mighty Handful” a.k.a. the group of big symphony boys who were always mad at Tchaikovsky for not writing purely nationalistic music and instead going off on his little impressionistic adventures.) It inspired Rimsky-Korsakov to start writing a symphony, which he took with him as a little passion project while out on a nearly 3-year expedition around the world. See!?! My guy looooves his cruises! Eventually Rimsky-Korsakov traded in his sea-faring job for a clerical position and started composing all the time.

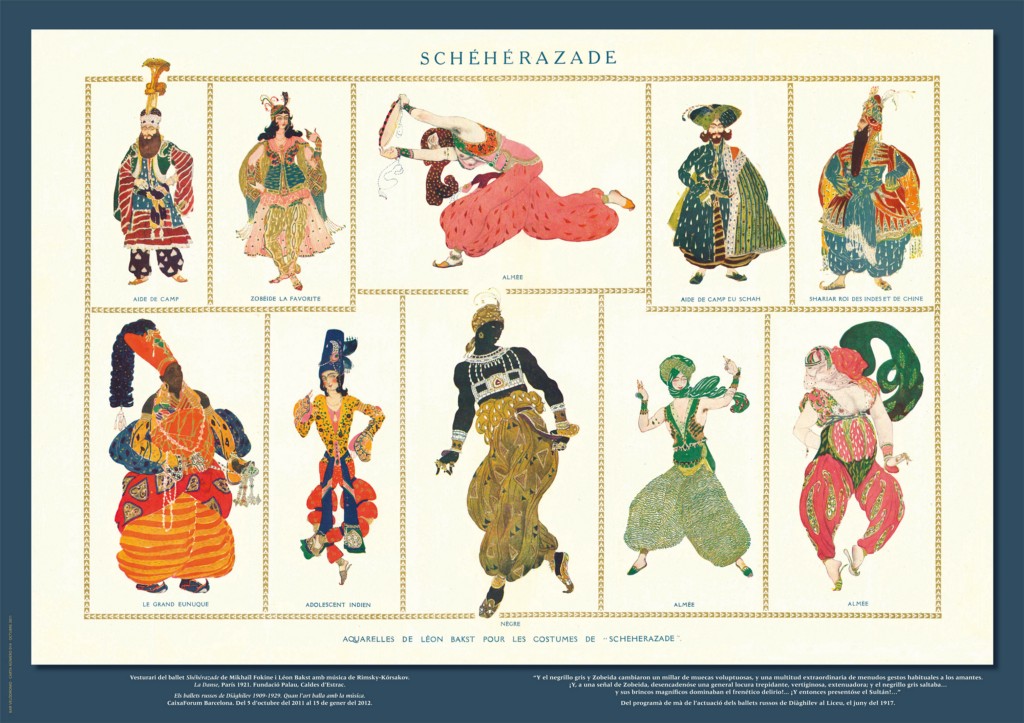

So you get why my guy was composing pieces with titles like Capriccio Espagnol and Scheherazade: he was obsessed with the culture of “other,” be it the folk music of Spain or “the East” or wherever. He loved to live vicariously through his music, and he wasn’t, to his misfortune, living in the 21st century where someone could be a sailor and a composer and no one would bat an eye. (Can men really have it all?) And so, Scheherazade (conducted here by Thomas Beecham, recorded in 1954 by the Royal Philharmonic) is a symphonic suite inspired by One Thousand And One Nights a.k.a. Arabian Nights; pick your preferred title, I don’t care. Scheherazade, of course, is the name of the queen in One Thousand And One Nights who, in an attempt to delay her own death by an all-women-should-die sultan, tells a story — a collection of stories, really — that last, you guessed it, 1,001 nights. Good strategy! Men are easily distracted. As a symphonic suite, you’d think Scheherazade would qualify as programmatic music, especially as each movement has a title surround one particular tale or characters, but Rimsky-Korsakov actually intended for each movement to exist as its own anecdote for a listener to project their interpretation of the music onto. The movement titles, in fact, were suggested by a student, Anatoly Lyadov, and not organically a part of the piece as Rimsky-Korsakov intended.

The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship starts off the suite, its opening melody distinctly representative of the sultan. Ominous and foreboding, this theme quickly gives way to the quiet persistence of the woodwinds, and then to a violin solo representing the queen. From there, melodies flow in and out, motifs change and shift through the suite. There’s no sonata form to latch onto, but it’s easy to see why Scheherazade has resonated with so many audiences: its details are lush and full, the music itself clever and wondrous. It has a choppy, forceful power to it like sailing on a wild and unpredictable sea, while at the same time intercut with melodies like the 6:16 mark, sweet and unassuming. Also… okay… here is a weird thing: the Beecham recording of Scheherazade on Spotify lists the first movement as The Sea (yup) and (gotcha) Sinbad’s (his?) Soup (what?????). His soup??? Literally everything else I have referenced calls this movement The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship. I mean — the story from One Thousand And One Nights is about a ship! Was I having a stroke when I was writing this? Honestly… I don’t know. Anyway. A fun mystery for me and my readers. Please let me know if you have any insight as to why this movement is labelled as soup.

I was most familiar with the second movement, The Story of the Kalender, as in when I started listening to it, I was like, “oh, right, obviously.” Kalenders were monk-like men who roamed around markets and performed magic tricks and told stories, but the one in question from One Thousand And One Nights is like half-prince, half-kalender which is neat and nice for him. In turn, you wind up with this initial melody that seems a little more regal and controlled than the movement prior. It’s almost like a fanfare in parts, “here comes the guy who is both a magical storyteller but also a nobleman.” A hero’s journey, in fact!

The third movement, which, despite this not being a symphony does take on sort of a Romance vibe, which I do mean in the capital R-Romance type of way, although it’s entitled The Young Prince and The Young Princess, so maybe in the r-romance way too. It’s perhaps the most simple movement to listen to. It plays like a courtship, a dance, no doubt, between two people or two factions of the orchestra. It’s got harp, you know? The lovers’ instrument (go with me). It should certainly be clear by this point that, even acknowledging of this fetishization of “the East,” Rimsky-Korsakov does achieve this firm sense of place in Scheherazade. The music is curious and mysterious, no doubt wildly different than the sound of French or German classical music at the time, and invokes setting so much more so than it does story or capital-T Theme like “fate” or “God” or “beauty.”

Festival at Baghdad. The Sea. The Ship Breaks Against a Cliff Surmounted by a Horseman. is the longest title of a suite in living memory (I’m sure this isn’t true but I refuse to Google it). This fourth and final movement features recapitulations of some previous themes and it really, fully, leans into this desert adventure tone. “The other is good, and exciting, and mysterious, and romantic,” writes someone who spent their childhood obsessed with the idea of being on a big boat. Scheherazade both others “the East” in broad strokes, but at the same time, it also feels like a big piece of nostalgic music, obsessed with youth and love and these themes that actually are present in other big classical suites. It’s not programmatic because maybe… it’s more about… Rimsky-Korsakov than One Thousand And One Nights? Nice, I figured it out. But seriously, there’s a theme that creeps in around the 9:46 mark, a sweeping and lovely romantic melody that feels like you might as well watch a little boy chase a kite around an open field while listening to it. And I know that’s not Rimsky-Korsakov’s reality, but it does attempt to capture a feeling lost, a feeling misplaced, one only perhaps located very far away.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.