Revisiting The Prophetic Verse Of Eve Merriam's 'The Nixon Poems'

It perfectly captures the anxiety of watching folly unfold daily

Four years before Watergate, Eve Merriam published The Nixon Poems, a collection dedicated “to the Constitution of the United States of America.” Merriam was not your typical satirist. She won the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1946 for her collection, Family Circle, and primarily wrote verse for children — until her controversial 1969 collection The Inner City Mother Goose gained fame as one of the most banned books in the country.

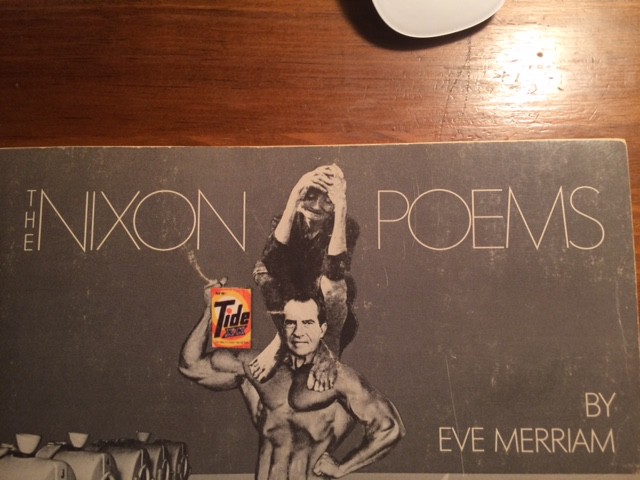

The Nixon Poems is a surreal ride with a campy Pop art cover, complete with a blurb from Norman Mailer (“I didn’t think there could be anything new in anti-Nixon jokes, but Eve Merriam turns the subject into very funny and very painful little poems”) and illustrations from John Gerbino, a friend of Diane Arbus from Harper’s Bazaar. In a review upon its release, Kirkus praised the book, but wanted more: “We wish she had been still funnier — or more pointed, or stylish, or even malicious. Anything to ease the depression of seeing the national stalemate in verse. In thirty years or so this should be a very desirable number, with its quintessential mood and poppy graphics. We’ll have another look then.”

I had a look 47 years later, and agree that the book visually and stylistically captures a certain moment, but let me assure you: The Nixon Poems is frighteningly prophetic. Nixon–Trump comparisons are common, and will likely become even more so as the months go on, but I couldn’t believe the Trumpian visions that Merriam captures.

Here is the third poem in the book, “Program”:

When the new President

introduced his cabinet

he sponsored them

on evening primetime

presenting them as men who all have

“that extra dimension”

and if the Presidential phrase

seemed fussily familiar or shopworn

from being bandied about

for brands of cigarettes cough drops shaving cream containers

well what’s wrong with

a bona fide business connection?

The Nixon Poems is one woman’s personal condemnation of an administration. The first line of the book is “I cannot pronounce his Presidential name.” The book is written as an act of disbelief; the collage art that surrounds the poems feels less flippant than an act of desperation. She’s exasperated and exhausted. She stumbles over his name “like getting up at night / and groping down the hall.” “Nowadays” perfectly captures the anxiety of 2017: “I wake in the morning / with a stone in my head // a stone in my heart // stones for legs // and I / walk.”

These poems might sound melodramatic. After all, the losing side is always angry and fairly bitter. But the Nixon of this book and the Trump of our contemporary reality show are the same. Nixon’s proclamation 3919, the National Day of Participation, is declared in advance of Apollo 11’s moon landing, but “suppose they don’t land / / well, we could always keep it as / a National Day of Mourning // There is a nixon style / everything is good for something.” You can imagine 45 doing that.

More prime Trumpian lines from “Metamorphosis”:

I lead the crusade against water pollution by a secret plan that

will be revealed at the proper time

I invite Billy Graham to bless the official White House

bowling alley

And I do not change

Merriam so perfectly captures the anxiety of watching folly unfold daily in “My Prez”:

of whom

else can I say

that

when he does

something good

there is

a bad reason for it

The Harvard Crimson took a dim view of The Nixon Poems, not because of Merriam’s verse, but because of the subject matter:

No great poetry can be written about Richard Nixon, for he is not important to men or to mankind in general. The attempt to enlarge him into a universal figure either for poetic glorification or vilification is doomed by his essential lack of distinction.

What should the poets do about Trump? Write about him. How should they write about him? However they want. Although The Nixon Poems somehow feels even more accurately recast as The Trump Poems, we need our own considerations and consternations. Let them be high-minded, or let them be absurd. Art has to work itself out. That process, especially with satire and humor, is often a mess. The critics will have us believe otherwise, but they are looking for patterns in the rubble. Our energies are wasted on critiquing the nuance of our contemporary political satire: it is like standing amidst the tracks and pondering their imperfect design, as the train barrels toward us.

Nick Ripatrazone has written for Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, Esquire, and The Paris Review. He’s on staff at The Millions.