Germans and Americans Both Love Their Damn Lawns

Deutschland über us.

I’ve finally figured out how we Americans can repair our newly fractured relationship with Germany: LAWN SUMMIT. And not a moment too soon: There otherwise seems to be little gemeinsam (guh-MINE-zamm), or in common, between us and the leaders of the free world. Germans are Jets, we are Sharks; they are Žižek, we are Chomsky; they are Bayern München, we are a country that doesn’t believe soccer is a real sport. AND YET: Despite the fact that it’s a blight on the ecosystem, a froofy holdover from the days when everyone wanted to pretend they lived on Downton goddamned Abbey, and a monumental waste of time, energy, water and space, both Germans and Americans can’t get enough of a lawn. Great.

Or at least that’s the case according to Spiegel columnist Benjamin Schulz, who, after posting a slideshow of his own lawn-based ignominy and a plea for reader advice, received such a deluge of responses that, he says, “If there were a German Lawn Party, it would win a seat in the Bundestag for sure.”

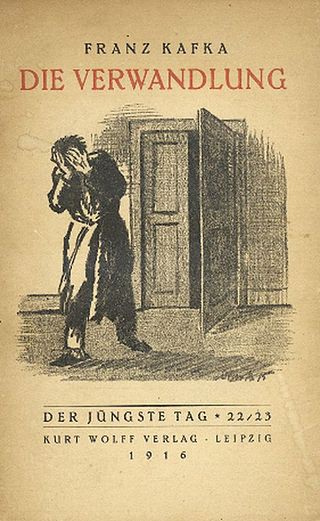

Of course, Schultz concedes, there’d be factions in the Lawn Party (where they’d perhaps hold fundraisers during lawn parties), “just like in the Greens.” The Realos faction (ray-AL-ohs) would insist that “weeds, moss and bald spots are inevitable” — with, by the by, the German word for “weeds” numbering among the best German words of all time: Unkraut (OON-krowt), literally “un-cabbage,” or a plant unfit for human consumption. (FUN FACT! This is actually a recurring construction in German, with fun examples such as Unwetter, or OON-vett-ah, “un-weather,” the word for “thunderstorms,” i.e. weather unfit for human interaction, and perhaps the best known example, Ungeziefer, or OON-guh-TSEE-fur, the untranslatable word for whatever the hell Kafka’s Gregor Samsa is, a hideous insect-like household pest unfit for Leviticus-style sacrifice unto the LORD.)

Meanwhile, back in the factions of the imaginary but dominant Lawn Party (and its imaginary but probably very fun lawn parties), we have the somewhat less prone to linguistic flights of fancy Fundis (FOON-dees), who would counter the Realos with the more Nietzschean belief that everyone can have a “perfect lawn” with enough “will and commitment.” The world of lawns seen from inside itself, apparently, is the Will to Uncabbage-Free Power, and nothing beyond that.

I tell you h’what, man: Germans’ obsession with the stupid patches of grass in front or behind their houses rivals only Hank Hill’s, and I guess we should be thankful for this tiny moment of intercultural understanding, even if it is about something terrible.

Germans, Hank, and even my mom; they’re all in lawn cahoots. I don’t know what it is about moms and lawns, by the way, but mine would be right at home in that Spiegel column. Some of Schulz’s readers, for example, recommended watering, at least once per week, one’s dog-poop farm and very reluctant Slip’n’Slide host (WHY HAVE A LAWN IF YOU CAN’T HAVE A SLIP’N’SLIDE, MOM???? WHY???).

While Schulz himself can’t see wasting all those liters of potential drinking water on a patch of overly-managed fake-wilderness that people use maybe three times a year tops (he bought a German thingy that traps rainwater; I’m sure it was expensive and will last until the year 3050), the same cannot be said of my mother, who, while everyone else on her block heeds the city’s “recommendation” to let one’s lawn die during the summer drought, defiantly runs the sprinklers so that her grandchildren, too, may experience their first bee stings while they enjoy a Crocodile Mile in their dreams.

Anyway, other important (and heavily debated) rules for German lawn care include the proper length to raze one’s Rasen, which is apparently “not shorter than three, and preferably four, centimeters,” and how often to fertilize, which is the second-best new German word I learned this week, düngen (DUUUUUENG-un), a verb that literally means “to dung,” ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha. “No, Jürgen, you can’t have your allowance! You haven’t dunged the lawn.”

You might think, then, that Germans’ need for the world’s most perfect yard — the German word for which is Garten, which encompasses not only garden-gardens but courtyards, patios, gazebos, cupolas, koi ponds, mini-forests and the aforementioned lawn, Ungeziefer of green things — would be limited to those Germans who live where yards can be had, i.e. in the suburbs and the country.

You would be wrong.

Enter the Schrebergarten (SHRAY-bur-GAR-tun), the bizarre tiny enclave of yards and their adjoining huts that borders most every major German city. Originally parceled out in the 19th and 20th centuries for purposes of outdoor exercise and wartime food cultivation, these tiny, coveted patches of rented land passed down from generation to generation are home to gnomes, vegetables, flowers, even smaller lawns, and itty-bitty Häuschen (HOY-chen), or li’l houses, that generally contain kitchens, a little sitting area, maybe a bathroom, and zero beds because, as the wonderful blog Wunderbar! puts it, “one of the many hundreds of rules is that a Schrebergarten is non-residential, and rules are there to be obeyed.”

Germany Holidays: Schrebergärten, Germany’s suburban garden kingdoms

This, by the way, is where the US-German Lawn Summit would go to das Düngen, just like everything else our country touches. For just as Germans believe (and we most certainly do not) that there is a universal right to health care, they also believe there is a near-universal right to a goddamned lawn, even if you live in a seventh-floor walkup in a factory building not zoned for residence. As our American Unpräsident’s behavior slides further into King Lear territory, and I contemplate more seriously the thing Jews can do where we get German citizenship, I prepare for a better life in all ways but one: The lawns, it seems, are überall.

Bright side: At least I can found the Slip’n’Slide Faction of the Deutsche Rasen Partei.