The Emperor Of Air

How a 19th-century French lawyer crowned himself a Patagonian king.

In 1895, an unfamiliar flag appeared above the rooftops of Mogador, today’s Essaouira, a port on the southern coast of Morocco. It was white and blue. In its center stood three mountains, crowned by a rising sun. One corner held an indigenous Chilean dressed in war paint; another, a guanaco (a kind of wild llama). A Liberty cap, stars, daggers and scales completed the eccentric design. It belonged to the Kingdom of Patagonia, whose consulate had just opened its doors.

At the time, Mogador was home to many consulates, and having a consulate was a necessary condition of doing business in Morocco. Consuls acted outside the scope of Moroccan law. They were exempt from taxes, and were able to extend this protection to as many people as they wished. This opened the door to many profitable abuses. Andorra, San Marino, Guatemala, Haiti and San Domingo, Siam and the Sandwich Islands, Kotei, Acheen, the Transvaal and Orange Free State all maintained representatives in the city. But Patagonia was something else entirely. Some Moroccans in town wondered whether Patagonia was a province of France. A few Jewish traders insisted that it was in Argentina, or in Chile and that it was not independent at all. They were right. But then, how to explain the presence of the consul, who went by the name of Abdul Kerim Bey, dressed in a fez and spoke a little Turkish and no Arabic, and who seemed to be in actuality an Austrian army Captain named Geyling?

I first read this story when I was teaching Moroccan history to a class of high school students in Tangier. It stayed with me ever since as a sudden, strange mirage. But it was only much later, reading Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, that I learned the wider history behind it.

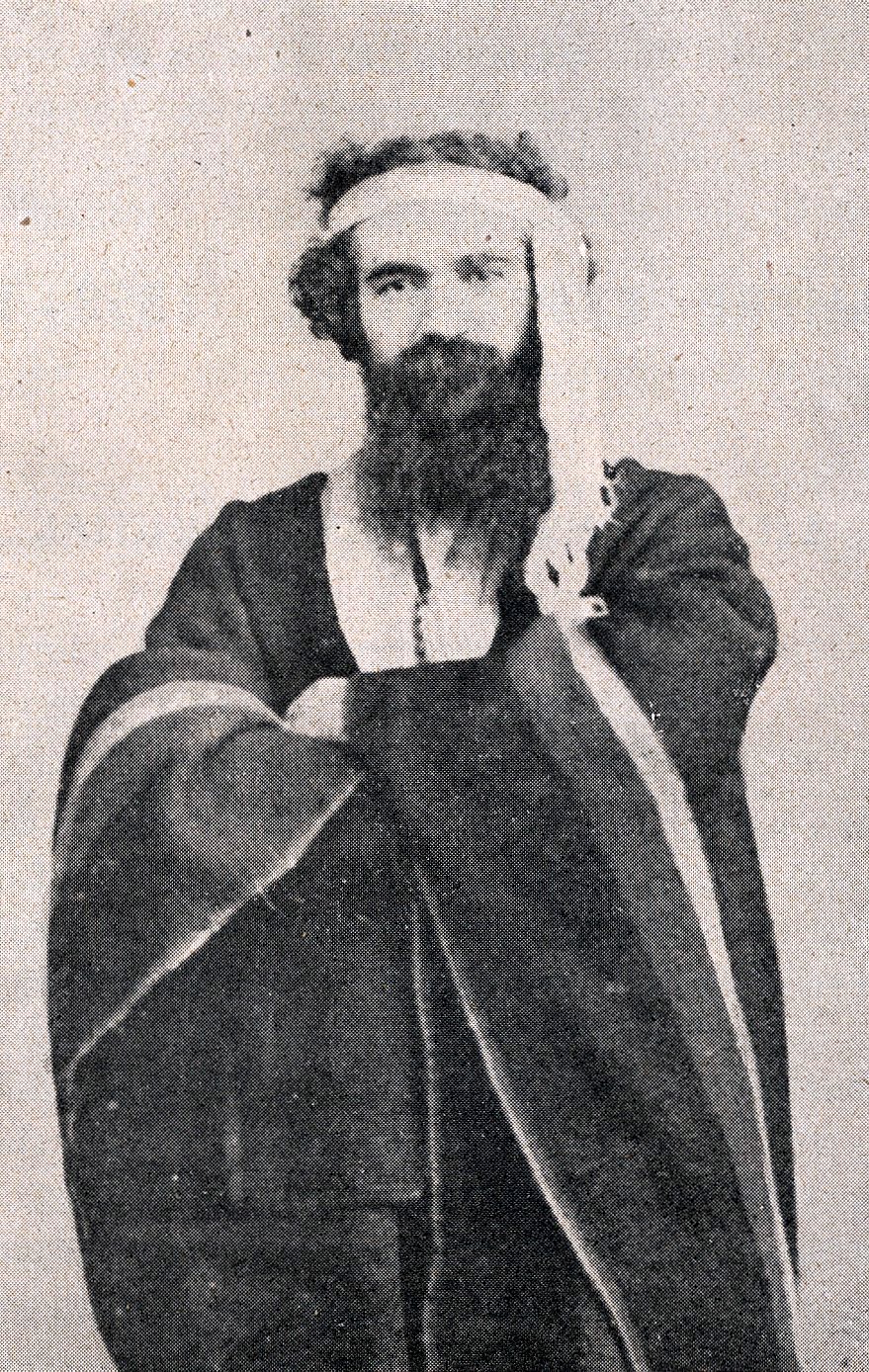

The truth was that the Kingdom of Araucania-Patagonia (its full name) did not exist, but it was not Geyling’s fantasy alone. Its story began some thirty-five years before, in the mind of a French lawyer named Orélie-Antoine de Tounens. Tounens was born in 1825. He was the eighth of nine children born to a prosperous farmer from Périgord. He believed his family was descended from Gallic nobility, and all his life, he wanted to better their station. From an early age he dreamed of restoring France’s fortunes in the New World. Napoleon and his nephew, Napoleon III, beckoned Tounens’s mind as examples of self-crowned kings. All he needed to do was to find a suitable kingdom. Reading Voltaire, he stumbled on the poems of a 16th century conquistador named Alonso de Ercilla. This settled his choice: he would go to Chile, and make himself king of Araucania.

Araucania’s name comes from its indigenous inhabitants, the Araucanians — known today as the Mapuche — a fiercely independent people who had maintained their independence from the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century all the way until the middle of the 19th. For all this time, the Bio-Bio River marked the frontier between slavery and freedom. North of it was the settled country of the Spanish settlers. South of it, all belonged to the Mapuche.

Ercilla was one of the conquistadors sent by Spain to Chile in the 1550s to subdue the Araucanians. Over decades of ferocious combat, Ercilla became awed by their indomitable courage. In the Araucana, his epic poem about the conflict, the Araucanians are heroes, equals to Hector and Achilles. Awed by their independence, he wrote “No king has ever ruled you/nor foreign power controlled you.” Still, as a servant of empire, he could not decide whether to depict the Spaniards as triumphant conquerors, like the Trojans from the Aeneid, or as villainous usurpers, like Caesar of the Pharsalia. He tells of one Araucanian chieftain who had his hands cut off as punishment for rebellion. He returned to his people, and used his bloody stumps as testimony to incite them to continued warfare. When his band was captured they refused to die by anyone’s hand but their own, and hanged themselves. Before this, the chieftain tells Ercilla that “We can be killed but not vanquished, nor can our free souls be enslaved.”

When Tounens arrived in Chile in 1858, the Mapuche were still unvanquished. Tounens waited two years before contacting them. In the interim, he studied Spanish and made contacts among the few French emigres who had already settled around Santiago and Valdivia. One of them, a farmer named Desfontaines, would become his staunchest ally and Secretary of State. In 1860, Tounens finally crossed the frontier between Chile and Mapuche country. He prepared the way for himself by making a gift of a piano to a Mapuche war chief named Mañil. According to a story recorded by the English writer A.R. Hope Moncrieff, when the chief received his gift, he had the hammers and strings removed from its insides and turned the piano into a bed for himself and his wife.

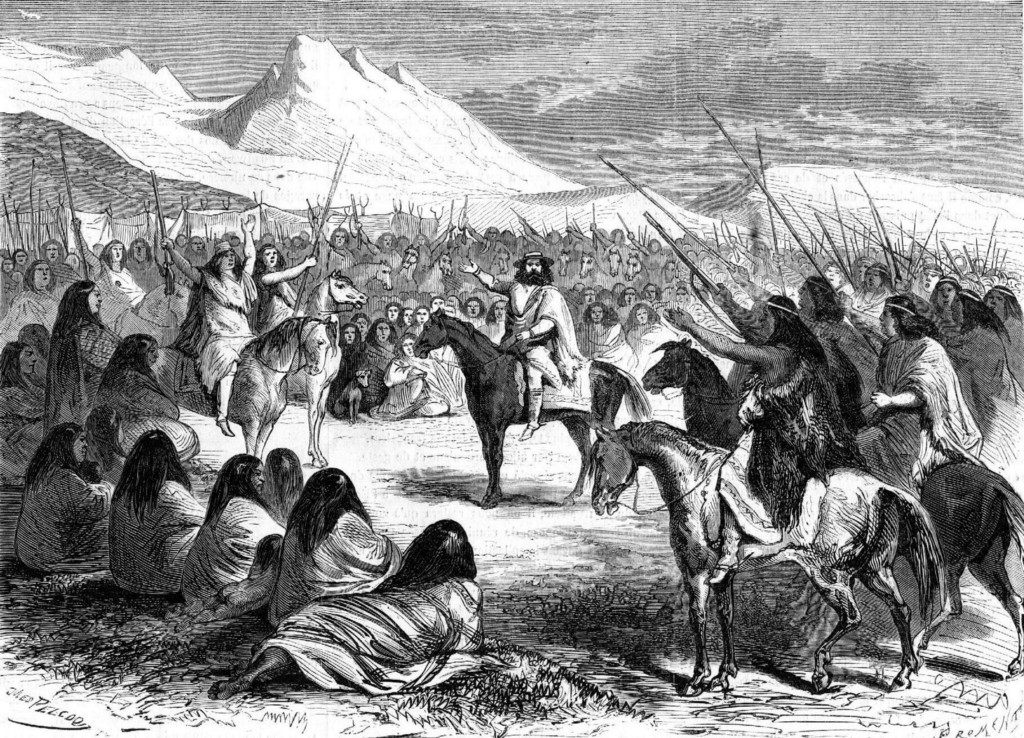

By the time Tounens arrived south of the Bio-Bio River, Mañil was already dead. But his successor, Quilapan, was equally interested in resuming war with the encroaching Chileans. Tounens seized his moment. Dressed in a royal costume he had made for himself out of a finely woven black-and-white poncho, silver belt buckle and spurs and long sword in a sheath inlaid with gold, he met with the Araucanian chiefs during one of their assemblies. Through an interpreter, he promised them weapons and ships with which to fight the Chileans, though he had neither.

In the following days he watched as they conducted a trial entirely on horseback; he envisioned a parliament conducted in the same manner. From the farm house of his friend Desfontaines, he proclaimed a constitutional monarchy with himself at its head. He drafted the constitution himself. It granted universal suffrage, individual liberty, legal equality and established proportional taxation. The monarchy, though, was reserved to Tounens — now King Orélie-Antoine I — and his family. In the event of his death, the crown would pass first to his father, then to his eldest brother, then on to his brother’s son. If all these should perish, it would go to “our well-beloved niece, Lida Jeanne de Tounens and her descendants in perpetuity.”

This remarkable document, encompassed in nine chapters and sixty articles, was ratified by an assembly of Mapuche chiefs. Possibly, they simply had a —King Orélie’s relationship with his subjects was dogged from the start by mutual incomprehension — but in any case, Tounens was convinced he was a king — a duly elected king, much like Napoleon III, or Euron Greyjoy. Soon, an emissary arrived from across the mountains; the Patagonian tribes were also interested in joining his kingdom (or asserting their independence). Tounens immediately annexed them to his realm and rushed to Valparaiso to let the world know about his deed.

The Chilean government ignored him. In 1862, he returned to Araucania from the settled part of Chile. The Mapuche were gathering for war. He rode with their army for the frontier. Finally, the Chileans took alarm, and made inquiries. While making his way back south across the frontier, Tounens’ interpreters betrayed him. Chilean soliders apprehended him in the act of taking a nap under a pear tree. Nine terrible months of imprisonment in the provincial capital of Los Angeles followed, during which he lost his magnificent black mane. Released, possibly thanks to pressure from the French consul, he made his way back to France.

He tried three more times to re-enter his kingdom. On the first attempt, in 1869, his arrival was treated as a miracle, since the chiefs had been told by he was dead. Soon though, the Chileans put a price on his head as a fomenter of rebellion, and, running out of money, he was forced to flee back to France. The second time, in 1874, he went in disguise, but was discovered and arrested. On the last attempt, in 1877, he contracted a terrible case of dysentery, which nearly killed him, and required that he be fitted with a silver anus. The following year, he was back home in his brother’s village of Tourtoirac, working as a lamplighter. By the end of 1878 he was gone, having died penniless in a Bordeaux hospital.

Questions remain: how did Dr. Abdul Kerim Bay/Geyling come into his consulship? According to the Scottish adventurer Robert Cunningham Graham, who met Kerim during his stay in Mogador, thought he might have been one of King Orélie’s hangers-on from his time in exile in France and Argentina. More likely, Kerim simply assumed that no one would question the existence of the Araucanian state in a place that was at once as cosmopolitan, and as cut off from the rest of the world, as Mogador. Indeed, the consulship was a front for more than just taking bribes. It turned out Geyling was involved in a scheme to sell guns to the tribes of Morocco’s south, and the consulship was his cover. But before the sale (strictly illegal under Moroccan law) could be concluded, Geyling absconded back to Austria, leaving his partner, one Major Spilsbury, stranded in a yacht off the coast with a cargo of repeating rifles.

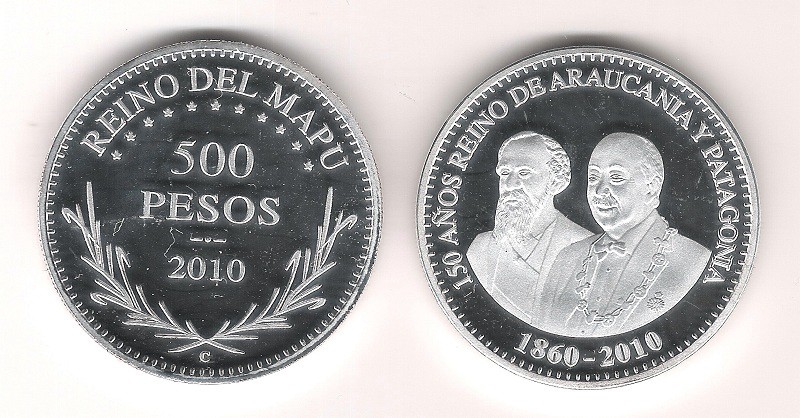

Meanwhile, in Périgord, the Patagonian crown passed from hand to hand according to rules set down by its founder. Seven kings and one queen have by now had a turn on the imaginary throne. Quite a dynasty, even if it is electoral. Their exploits are detailed in issues of the official Araucanian newspaper, The Steel Crown, their faces shine on the medals issued by their Royal Mint. But that isn’t to stay the succession always proceeds without a hitch. Last year, the throne passed to Jean-Michel Parasiliti di Para of Paris, a 73-year-old confidant of the former king. His opponents rallied to the cause of a rival, a 20-year-old named Stanislas Parvulesco, who was immediately denounced as a renegade. In the pages of the (French-based, but also digital) Araucanian press, the quarrel has grown bitter. Neither claimant seems ready to back down.

In between his voyages to and from France, King Orélie published his memoirs, bestowed titles, founded a newspaper La Corona de Acero (“The Steel Crown”), and searched for a bride. While in France in the 1870s, he was approached by another visionary: Eugène Pertuiset, big game hunter, inventor of exploding bullets, and subject of a portrait by Manet. Pertuiset offered to give him some valuable intelligence. He claimed to know the location of an immense treasure buried by the Inca in Tierra Del Fuego, which he had learned it with the help of a medium or seer. The proposition was tantalizing, but Orélie dismissed him. He was a king, and had no time for idle dreamers.