Open Up and Say AAH!

Dentistry is vile

Long before electric drills and saliva vacuums, we’ve been wary of dentists, and for good reason: the history of what we now call “oral health” is well, rooted, in thousands of years of discomfort, violence, and fear. (It’s not for nothing that Steve Martin sang about parlaying his adolescent penchant for inflicting pain and suffering into a career in dentistry in 1986’s Little Shop of Horrors.) The patron saint of dentistry — yes, there’s a patron saint of dentistry — St. Apollonia only became so after a mob of religious men bashed in all of her teeth and threatened to burn her alive (this was Egypt in the second century AD). In medieval paintings and stained glass, St. Apollonia is typically pictured with a pair of blacksmiths’ pliers — the instrument long associated with traumatic tooth extraction.

How else to rid oneself of the malevolent tooth worms believed to cause decay? In early Chinese medicine, you might have tried this home remedy:

Roast a piece of garlic and crush it between the teeth, mix with chopped horseradish seeds or saltpetre, make into a paste with human milk; form pills and introduce one into the nostril on the opposite side to where the pain is felt.

In second-century Rome, the leading physician prescribed pickled chrysanthemum root as a palliative. Wiser doctors suggested opium.

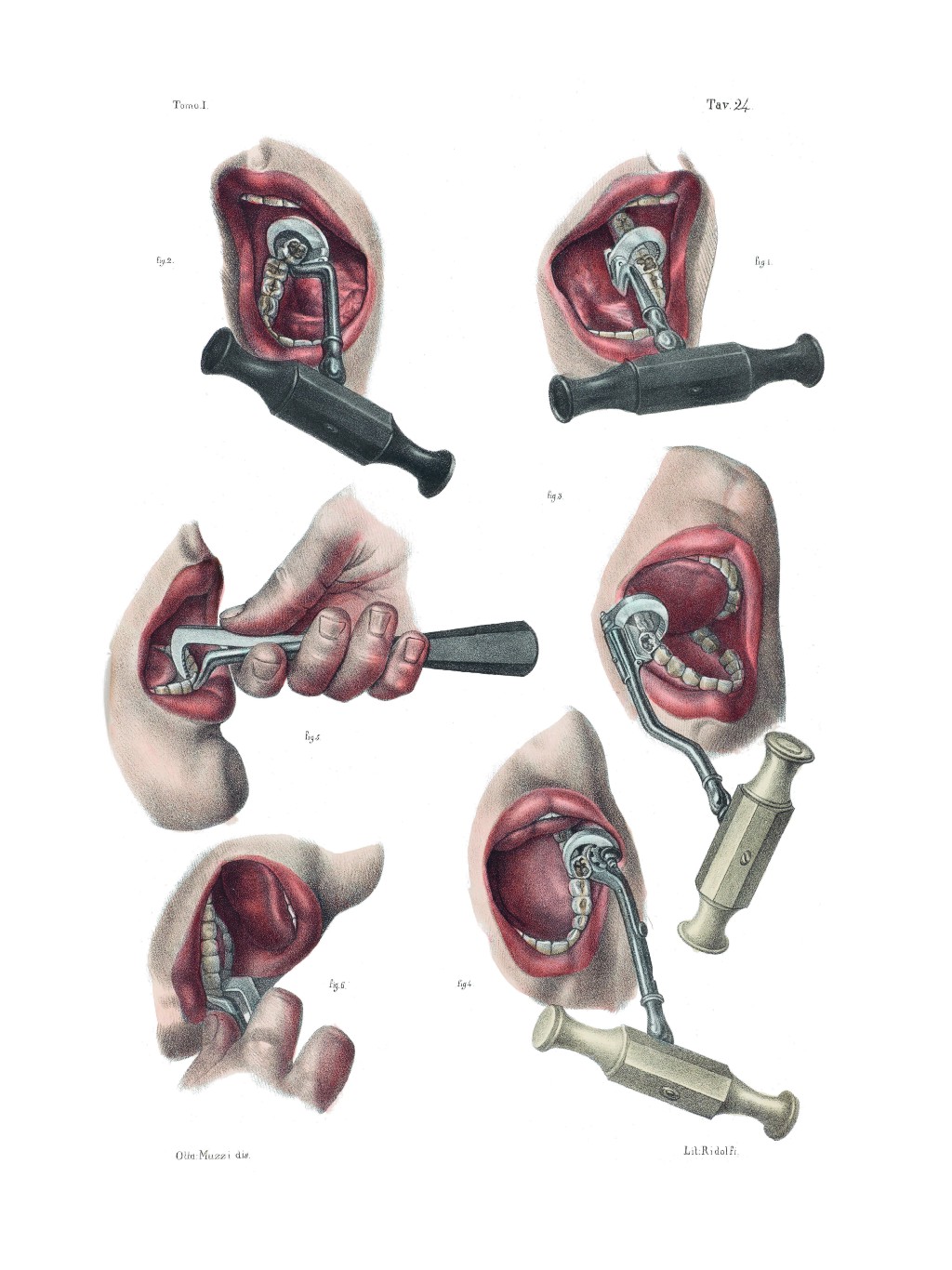

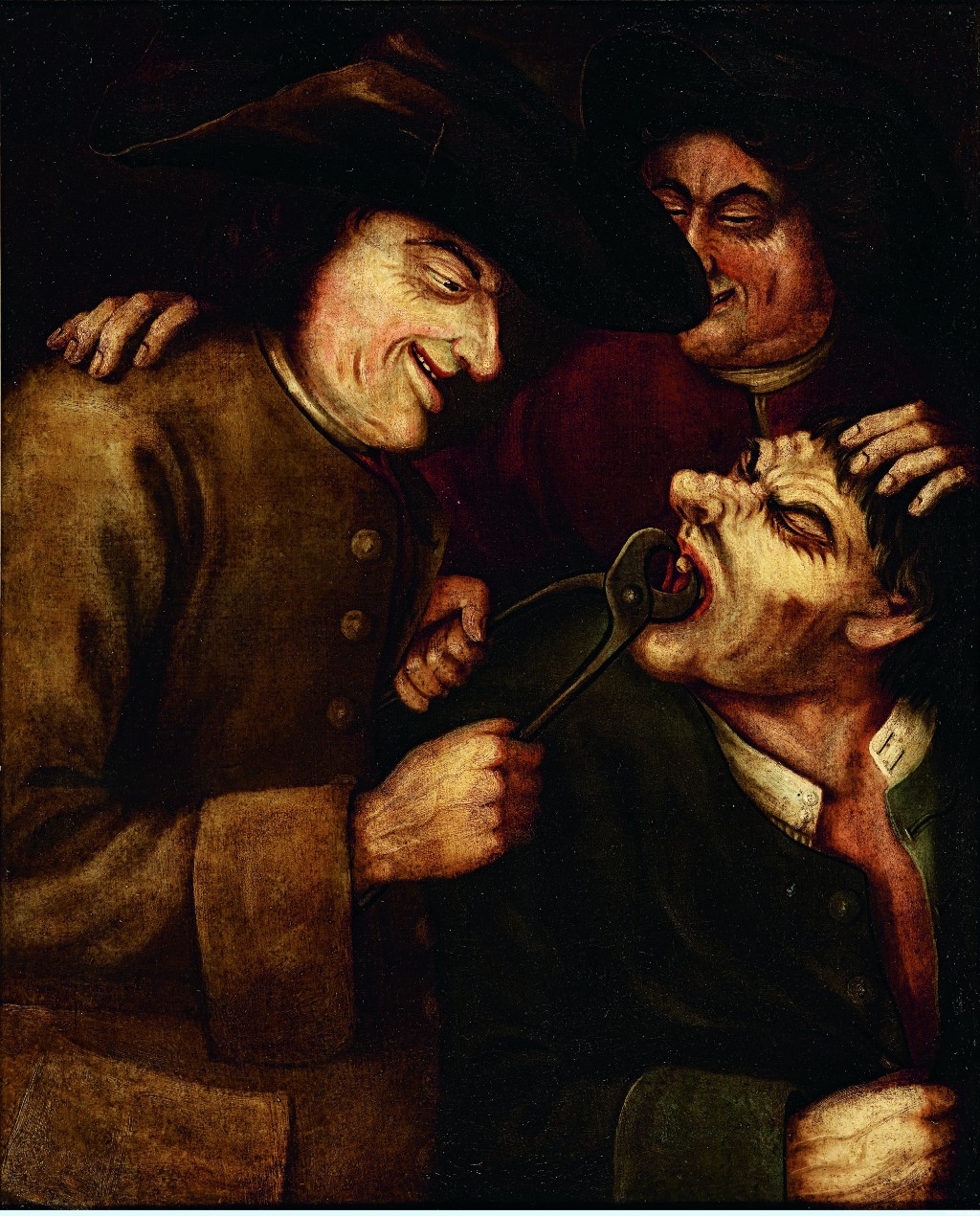

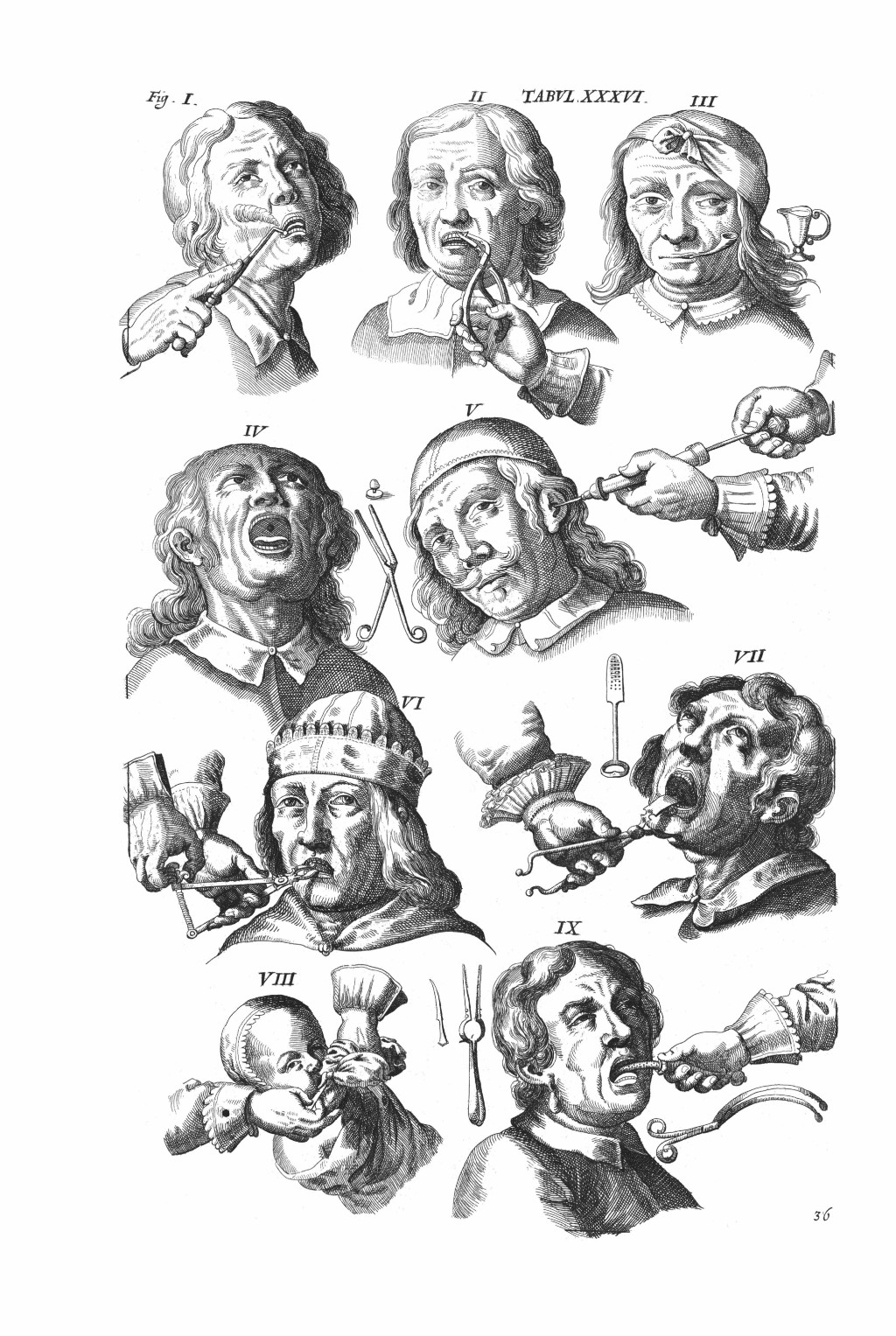

But yanking those putrid incisors was the only viable long-term solution, prompting a visit to the village blacksmith, with his handy pincers, or perhaps to the cooper, given that the hooked ‘pelican’ tool preferred by medieval tooth-pullers “originated as a device for pressing iron hoops onto barrel staves,” according to Richard Barnett’s The Smile Stealers: The Fine and Foul Art of Dentistry. “Patients sat on a low stool, their head held between the tooth-puller’s knees, while he locked his pelican onto the offending tooth and sought to unseat it.” Alternatively, he might try the ole dental key, a “cross between a corkscrew and a door key” that tightly gripped the offensive bicuspid while the pseudo dentist twisted and turned as if “opening a lock.”

These are the kind of squirm-inducing trivia one picks up while reading Barnett’s newest book, the third in his unofficial “tr-ILL-ogy” of copiously illustrated and elegantly designed medical histories, following Sick Rose; Or, Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration (2014) and Crucial Interventions: An Illustrated Treatise on the Principles & Practice of Nineteenth-Century Surgery (2015). Like its predecessors, The Smile Stealers is a quirky and fascinating book that shines a spotlight on London’s eccentric Wellcome Collection, from which the gruesome imagery is sourced. All three might be fairly marketed as coffee-table books for the slightly twisted.

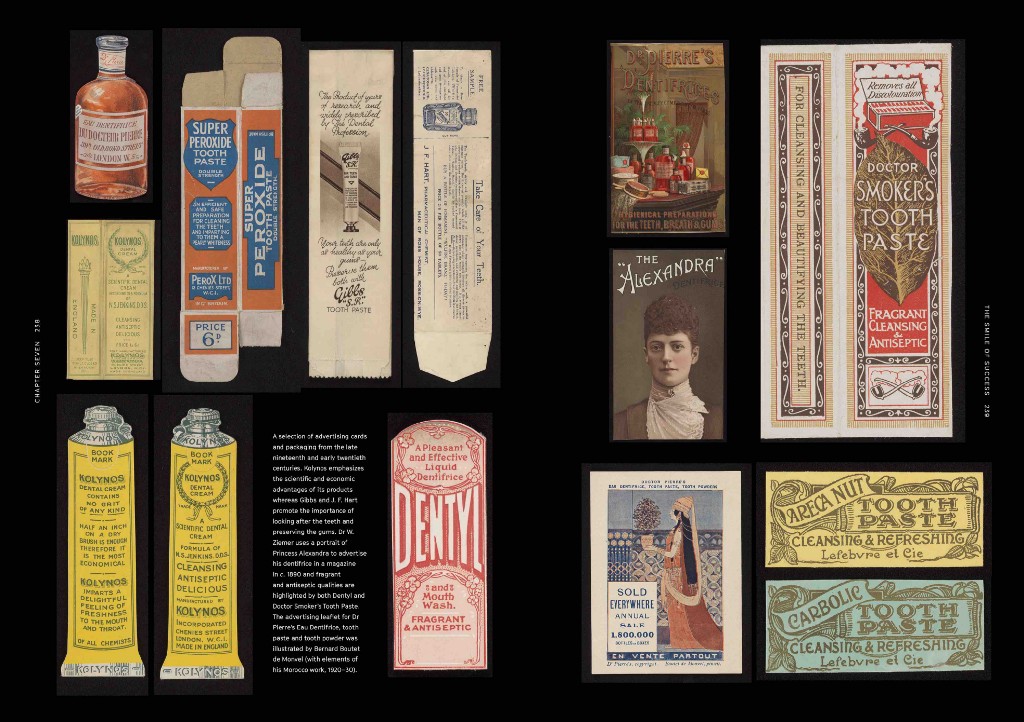

The 350 illustrations appearing in full spreads and peppered throughout the text are central to the book’s grotesque charm. They range from reproductions of oil paintings to anatomical engravings to archival images of patent medicine packaging to photographs of archaic dental instruments and hardware. Perhaps because of the distance afforded by modern medical technologies, anesthesia chief among them, The Smile Stealers is genuinely fun to read.

We get a glimpse of the “most famous false teeth in history,” which belonged to George Washington, and were NOT made from wood. The lower plate holds human teeth — harvested from a cadaver or a pauper — and the upper chiseled elk molars. “In another setting they could be a pair of castanets imagined by Francis Bacon — a ghastly, disembodied grin that might pursue you, gnashing, through your dreams,” Barnett writes. Washington’s spare pair, he adds, was constructed of walrus ivory, a.k.a. ‘seahorse teeth.’ Vexed by smelly, uncomfortable dentures, it’s no wonder the first president was known to be a wee bit prickly.

Despite the reputation of dentists, several lively characters emerge in Barnett’s studious yet sprightly narrative. One is Jean Thomas, la perle des Charlatans, an eighteenth-century Parisian tooth-puller who literally wore a feather in his cap. As Barnett writes,

Myths multiplied around this Rabelaisian figure: he weighed as much as three men, he ate as much as four, and if a tooth proved obdurate he would rock his pelican onto it, lift his client off the ground and allow their own weight to perform the extraction.

Sometimes the jaw came with it. Thomas’s nemesis, Pierre Fauchard, the “first practitioner to call himself a dentiste,” wanted to professionalize dental care in the same way that surgeons had, once they stopped moonlighting as barbers. Fauchard tried to convince folks that if they cleaned their teeth regularly, they would suffer fewer toothaches.

It took a long time for that crazy notion to catch on, and in the meantime, turn-of-the-twentieth-century showmen-dentists like Painless Parker, continued to dose patients with whisky and cocaine and pluck their pearly whites. Parker claimed to have snatched as many as 357 teeth in one day, and he wore his plunder, like some kind of maniac, on a handcrafted necklace of human teeth (which, by the way, is something you can actually buy on Etsy). A Canadian who had relocated to Brooklyn, Parker advertised himself as “Painless Parker, Preeminent, Par excellent, Positively, Painless Perfection of Practice and Philanthropically Predisposed to Popular Prices!” He relished alliteration like a Ringling ringmaster.

Barnett steers clear of the orthodontic-industrial complex, which might have made for an interesting addition to his final chapter on America’s obsession with “the smile of success.” Ensured by daily upkeep (and the associated products), preventative check ups, and fluoridation, a flawless set of choppers manifested health and wealth in postwar America. Fair enough, but what about enforced beauty norms and the role of cosmetic dentistry? The twenty-first-century desire for bleached teeth, for example, is just as bizarre as tribal teeth sharpening or the capping of canines for a more fang-like appearance, known in Japan as yaeba teeth.

Though we may still dread dental appointments, The Smile Stealers reminds us, above all, not to be such cowards. Today’s skilled practitioner will likely refrain from pulling so vigorously on your rotten molars that he tears a hole in your palate that causes liquid to spill from your nose “like a fountain” every time you take a drink, and which can be fixed only by cauterization with a hot iron. At least not without offering you laughing gas first.

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places. She has written about books and history for Slate, The Guardian, LitHub, and elsewhere.