Ain't No Party Like A Propaganda Party

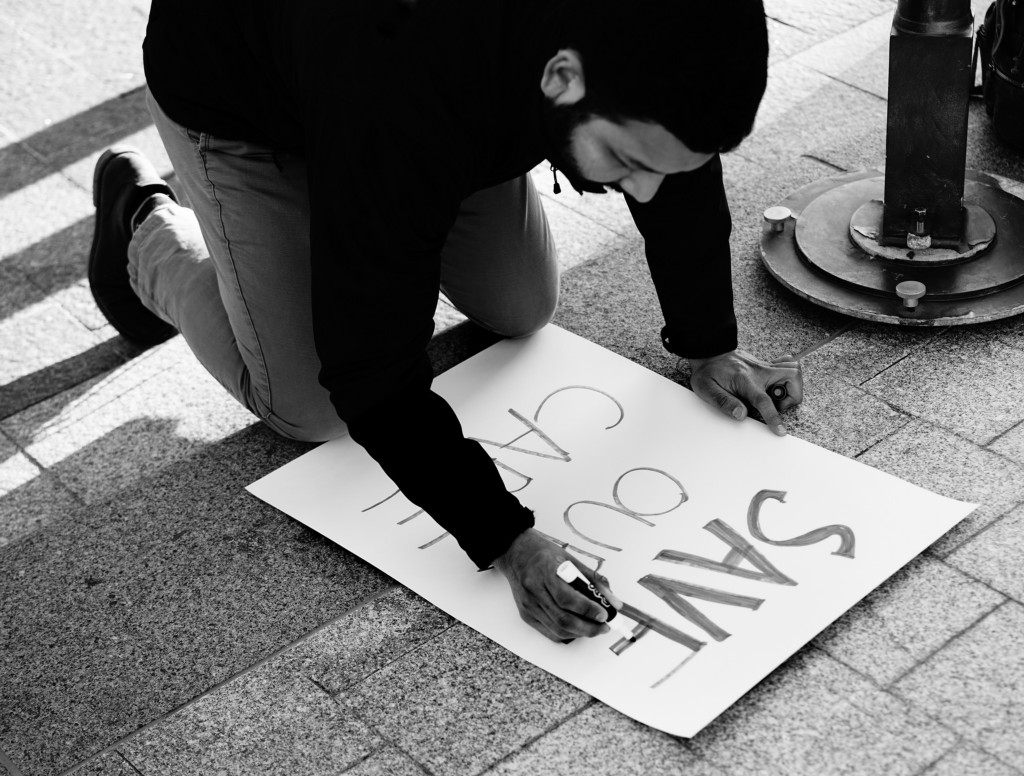

The art of the protest.

America may debate ad nauseam the meaning and legitimacy of our current Administration, but few adhering to any political creed would deny that the era of Trump has officially rejuvenated the art of the protest. The Women’s March in Washington, D.C., in January, was the largest single-day of protest in U.S. history, spawning hundreds of satellite marches in cities across the world, but what set it apart was not just its size but its creative brand of humor. In the months since, social media has been flush with “best protest sign” listicles, turning the language of political dissent into a mainstream battle of wits. Among the highlights from this past weekend’s March for Science were “Rising Seas — Adios Mar-O-Lago!,”; “Got Plague? Yeah Me Neither. Thanks Science!”; and “No Science, No Death Star,” carried by a protester wearing a Darth Vader mask.

“The signs are definitely getting more clever and accessible,” Josh MacPhee told visitors at a recent party hosted by the community-organized collective Interference Archive. MacPhee, who is forty-four and wore a button that bore the accessible, if not particularly clever, message “Chinga la Migra” (Fuck Border Patrol*, essentially), founded Interference Archive along with three partners, in 2011, to document the evolution of D.I.Y. and punk subcultures through the preservation of their ephemera. In other words, the archive, which sits in a one-story warehouse in Brooklyn, looks something like your packrat grandfather’s attic if all he hoarded was oversized serials, zines, vintage videos, and enough shoeboxes of buttons to dam the Gowanus.

MacPhee, who works as a freelance artist and designer, first got the idea of throwing a “propaganda party” after an arts nonprofit commissioned him to make posters about mass incarceration and he ended up with a surfeit of printed material. “I just thought, why not distribute this stuff to people who would rather not go to prison — or to an explicitly political event?” he said. MacPhee decided to throw a party to “reclaim the word propaganda,” at which people could exchange political messages and ideas and “walk away with a roll of stickers.”

While he spoke, MacPhee’s fifteen-month-old son, Asa, waddled by in a printed bandana and a sideways cap. Like his father, the toddler has faithfully attended all five of the parties that have been held so far, which have tackled themes from climate justice to sanctuary cities. Tonight’s theme was “sowing resistance.” “Movements inevitably ebb and flow,” MacPhee said, sipping a beer. “It’s important to create space where people can engage politically where stakes are not as high.” MacPhee watched as his son exploded a bag of rubber bands onto a stack of stencils that read “Eradicate Fascist Vermin.” He added, “In this country, we are so used to an environment where someone else does protesting and you watch it on TV. But here, we want to create a space where the lines are blurred and the pressure is a bit lower.”

Vero Ordaz, a genial labor activist in her mid-thirties, wore four buttons in a row that matched her tie-dyed sneakers. “Stubbornness, curiosity, and a dash of cynicism” had led her to attend the propaganda parties, she said, though she couldn’t recall exactly how many: “I’ve lost my concept of time since this Administration began.” She pointed to a button that read “May Day: Eat The Rich, Feed the Poor.” “Did you know I came up with this?” she said. “Well, most of it anyway.”

A speaker boomed out Bob Marley’s “Get up, Stand up.” A freckly thirty-three-year-old from Sunset Park dropped by to pick up prints that read, in thick black letters, “Oppression Breeds Resistance” and “Sanctuary City!” “My husband is North African and his side of the family is all Muslim,” the woman said. “We met in New York City thirteen years ago. Would we have been able to do so now?”

Despite stiff competition from the screen-printing and block-printing stations, button-making proved to be the most popular activity. “Are you manning this machine?” a visitor asked a young woman with a gelled pompadour and a septum ring. “I’m person-ing it,” she responded. As she helped a pair of women from Indiana print theirs (“Black Lives Matter”; “Femme Love”; “Fire to the Prisoners”), S. J. Avery, a seventy-year-old native New Yorker who was standing in line, recalled her own experience “person-ing” the button-maker at the War Resistance League forty years earlier. “We were anti-capitalism and anti-military, but boy do I still remember those button machines. They were so much heavier,” Avery said, shaking her head. “And you had to screw each individual part separately! Now, it’s so easy now even kids can do it.”

A little while later, a trio of kids did do it. Clutching a paper cutout that read, “Women are Not the Enemy,” Maya, a fifth grader at Park Slope Collegiate, turned to two friends, grabbing the handle bar of the machine, and whispered, “Do I just push this down?” The students had been asked at school to choose an article from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and make a sign that responds to it in some way. Maya described watching Trump’s Inauguration in class. “We were all so upset,” she said. “I stuck my middle finger up at the TV and the teacher didn’t even say anything.” “Omigod, Maya,” her friend Josh, an eighth grader, replied. Then, with a black marker in hand, he grabbed a piece of lime-green paper and wrote in bubble letters: “RACIAL EQUALITY.”

Jiayang Fan is a staff writer at the New Yorker.

*An earlier version of this article mistranslated the phrase “Chinga la Migra” as “Fuck the police.” The Awl regrets the error.