True Facts

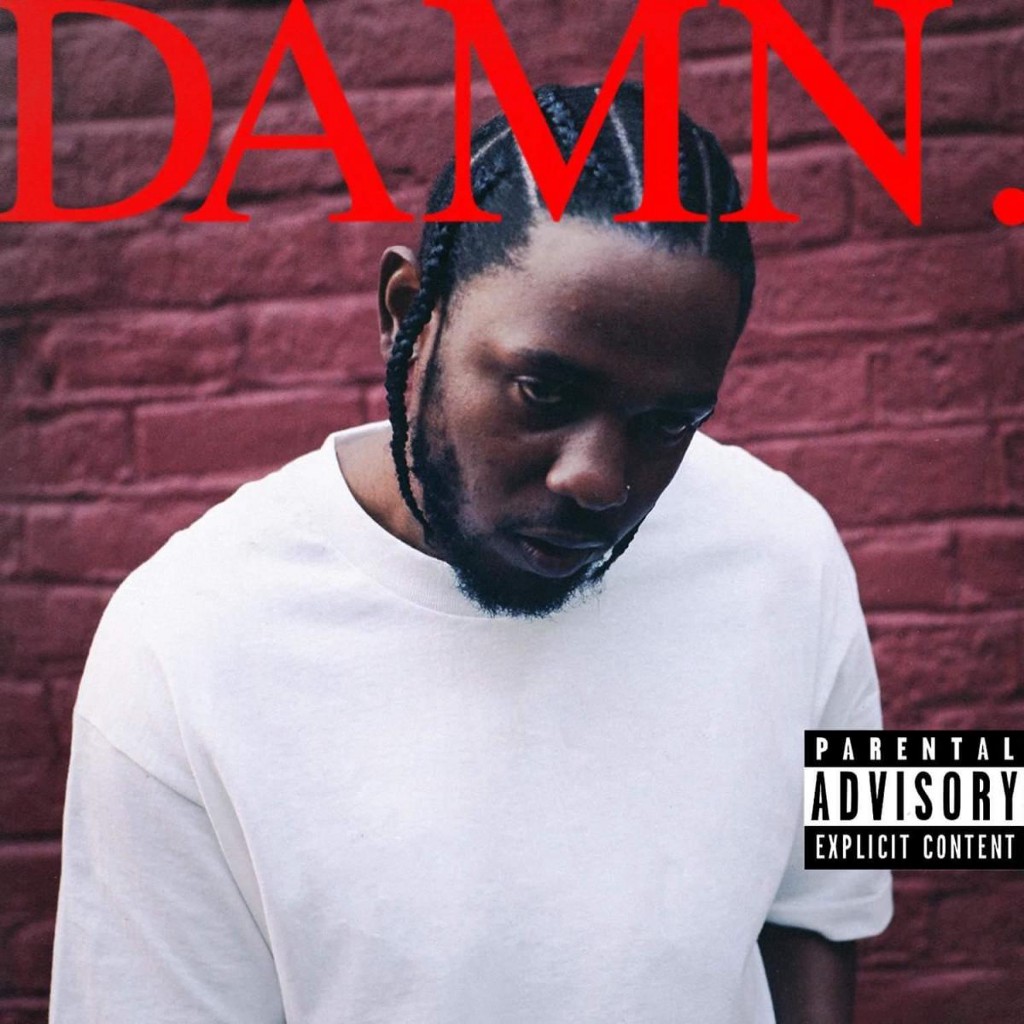

Kendrick Lamar’s “DAMN.” proves he’s a consummate storyteller.

Kendrick Lamar’s story has never been more accessible than in this moment, when he’s trying to overhaul it. Every artist works along two parallel narratives, that of their career, and that of their life; for all his prodigiousness as an MC and his obsession with the form, Lamar’s chief talent is trimming the distance between those worlds. He brings Infernal Affairs to Compton, and he brings Compton to the White House. Lamar and his newly introduced alter ego, Kung Fu Kenny, know how stories affect people, and with each new album, he advances the form’s function as a unit, and as its own singular world.

With the arrival of “DAMN.”, after a year of high-profile returns, the question of What Makes An MC has fresh blood. Except this doesn’t address Lamar’s skill as one of our great storytellers, full stop, a moniker generally bestowed to white men in glasses, with oeuvres of prose behind their names. But in tending to the specifics of his life and where he comes from, Lamar extends an invitation to everyone who listens. So through the vehicle of the album, and through giving us an “in” into his world, Lamar has plowed an entrance into that conversation: which of our storytellers will we allow to represent us? And how far are we willing to allow them to redefine the mainstream?

If “Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City” was his nod towards a day in the life, and “To Pimp a Butterfly” shadowed his ascendance to celebrity, then “DAMN.” feels like Lamar’s attempt to come back down from it all. Or it could be him grasping at everyone floating just underneath him. He tells a lot of stories on this record, from the origins of his label, to the perilousness of a walk around the block, but an overarching theme is the mundanity of our everyday decisions, which just happen to change the course of our lives. And Lamar knows how that sounds. He also knows that we know how it sounds.

Despite his latest turns at innovation, Lamar’s decision to string a narrative across an album is hardly innovative for the genre: since its inception, hip-hop has served as the storyteller’s medium. Whether it’s 3 Stacks, Jay-Z, Ice Cube, or Eminem, rap’s verified demigods traffic in narrative for solidification of their repute. It’s the serious lyricist’s calling card. And Lamar’s attempts master those same methods could be his tickets to entry. However singular a track may appear on its own (“i.” and “HUMBLE.” immediately come to mind), within the context of their whole, they take on an entirely different emotional weight: a major-key, guitar heavy clap-along becomes a strike against crippling depression; a braggadocious anthem is reintroduced as a meditation against excess.

But Lamar’s adherence to plot is also a means of reigning in his own public narrative: since a handful of missteps early in his career, he’s gone out of his way to avoid a certain brand of celebrity. He’s made some blunders, and now, instead of relaying his messages through gatekeepers, he’d prefer to speak for himself. He’ll surface as part of a dual entity every now and then, to usher the conclusion of an icon’s career, or to cosign a label mate’s come-up, but, for the most part, the rapper who said “all my life I want money and power,” he now seems resigned to the ailments that prestige can bring.

If Lamar’s career thus far has been a come-up, “DAMN.” is a gradual descent from the mountain. On “YAH.”, he sounds muted, absolutely monotone, a little sick of the situation at hand and a little resigned to the fruits that it will ultimately cease to bring:

My lastest muse is my niece, she worth livin’

He’s finally gotten the acclaim he wanted, but it’s a fuckton to chew on. He’ll stan for Killer Mike, but he’s “not a politician.” He’ll ride for Chance, but he’s not “about a religion” (although Lamar is, in fact, extremely spiritual in his own way).

As the record progresses, he continues adopting stories from the people around him: on “FEAR.”, he’s a black mother, anxious to instill fear in her child. He’s his father, slipping free biscuits to customers in gang territory. He’s the kids rolling around the streets of Compton, invincible and doomed, liable to the whims of the neighborhood and the nation:

I’ll prolly because I ain’t know Demarcus was snitchin’

I’ll prolly die at these house parties, fuckin’ with bitches

I’ll prolly die from witnesses leavin’ me falsely accused

I’ll prolly die from thinkin’ that me and your head was cool

I’ll prolly die from pressin’ the line, actin’ too extra

Or maybe die because these smokers

Are more than desperate

I’ll prolly die from one of these bats and blue badges

Body slammed on black and white paint, bones snappin’

After years spent building himself towards a come-up, Lamar raps himself back down to the Earth. He crafts his staircase track by track, extending those heights even as he descends. But how do you keep telling the story that needs to be told? How can you tell it in new ways? It is, inevitably, a narrative problem, and in a very good interview with Rick Rubin, Lamar acknowledges his father as the realist force in his life, and his mother’s impulses as a dreamer, before shouting out 2Pac, Biggie, Prince, and “the usual suspects” and noting the power of the narratives they wove:

The stories they were telling, whether it was fiction or not, these ideas that they were putting down made me believe any and everything that they were saying. Because it came from a space, whether being a realist point or imagination or whatever, because their ideas are so strong, and so heavy.

Lamar goes on to say that the characters and stories he inhabits are the voices and people complimenting his DNA; a motif he returns to on his most recent single:

Loyalty, got royalty inside my DNA

Cocaine quarter piece, got war and peace inside my DNA

I got power, poison, pain, and joy inside my DNA

I got hustle though, ambition, flow, inside my DNA

He knows these stories, and he’s lived them. Now he’s just trying to make them real. So he studies soul and rock and pop to inhabit them, cycling through mediums to bring them to life; and in this way, Lamar’s a student of the craft, as much as Roth or Paley or Dylan Thomas or Bob Dylan or Eugenides.

Home is Lamar’s chief preoccupation. So is the experience of leaving it, and the people he’s left behind — the folks whose lives he could’ve led, and the folks his success has entangled him with, and whether those parties can ever coexist. Compton, for Lamar, isn’t a series of statistics or a boon or a gutter or a type: it is a home with stories. It’s a city deserving of different forms and exploration, with people worth examining and prodding and glorifying. Lamar, like every other artist, has his motifs: the shadow of institutionalized oppression hanging over Compton, the tumultuousness of fate and chance, the fear of love, and the fear of failure. He returns to them on “DAMN.” because he needs to, because he knows that now he can tell them better.

When Mitchell S. Jackson, author of The Residue Years, was asked by The Paris Review whether or not he was worried about what he’d write next, he responded that he was, “in a way”:

But I don’t think it’s about having things to say, or waiting for things to happen to you so that you can write about it. It’s more about going back to that one story and telling it in different ways. I was listening to an interview with Jay-Z and he said that he’s only written about five stories in his whole career. He’s only had five things he wanted to say, but he’s said them differently… There are so many stories in a place. And nothing beats writing about home.

Lamar’s form certainly fits the times: over the past few months, a lot of us have felt our origins more vividly than we may have prior. Black-ness and Latino-ness and Asian-ness and other-ness have been magnified in a way that would baffle anyone who hadn’t already felt implicated over the past eight years. And while Lamar alleges that his aim is not political, he still lives in the world, and he has to deal with it.

On “LUST.”, he raps:

We all woke up, tryna tune to the daily news

Lookin’ for confirmation, hopin’ election ain’t true

All of us worried, all of us buried, and our feeling’s deep

None of us married to his proposal, make us feel cheap

He’s creating his own narrative to get by, just like the rest of us. And in a country that could elect a black man, only to immediately turn to an administration intent on erasing every last one of his imprints, variations in form are necessary to capture that history. The record has context, implicitly and explicitly, and that could be why “DAMN.” in West Texas isn’t the same as “DAMN.” in New Orleans, and all of this was intentionally, methodically plotted by Lamar.

An MC’s calling-card is his prominence, and who among his class is The Best, and while Lamar has made it clear that he’s engaged in that conversation, it’s one he takes less seriously than his role as a storyteller. He’s become the best chronicler of his own particular history. Which is, by turns, our history. His greatest gifts will be the stories he has to give. He knows they’re the only things that will last. And so Kung Fu Kenny becomes a muse, and a historian, despite whatever protests against him arise. Would that it were true of every MC.