The Dildo of Damocles

What happens when you connect sex toys to the internet?

About a year ago, Udo Schneider of the global software security firm Trend Micro plopped a big pink vibrator down in front of a group of journalists at a press conference in Hanover, Germany. With a few simple tips and taps on a nearby computer, those at the event later reported, he then turned it on — remotely and without the use of any app directly tied to the writing implement.

Schneider’s stunt was one of several presentations in recent years that have shown how easy it is to hack the growing field of digitally connected sex toys. Last summer, at the Def Con hacker conference, a talk on the vulnerability of the We-Vibe remote vibrator made it clear that some devices collect user data for analysis — in the case of that device, they did so at least partially without the legal consent of users. A month later, two women filed a lawsuit against We-Vibe’s maker. It was one of the first major cases on data integrity and privacy in sex toys, and the few information security experts who probe this odd niche suspect it will not be the last.

One might have assumed that sex toy developers, often self-avowedly sensitive to user discretion and privacy, would have adopted some of the highest security standards for their high-tech devices from the start. They have at least been responsive to outcry following recent revelations; they may even be incentivized (and able) to build some of the strongest privacy and anti-hacking norms in the world of smart devices. But it’s up to an alliance of hacker activists and consumers to push for those standards, as not every developer will recognize risks or take full responsibility for them on their own. Users need to know the risks inherent in those products, and how best to protect themselves.

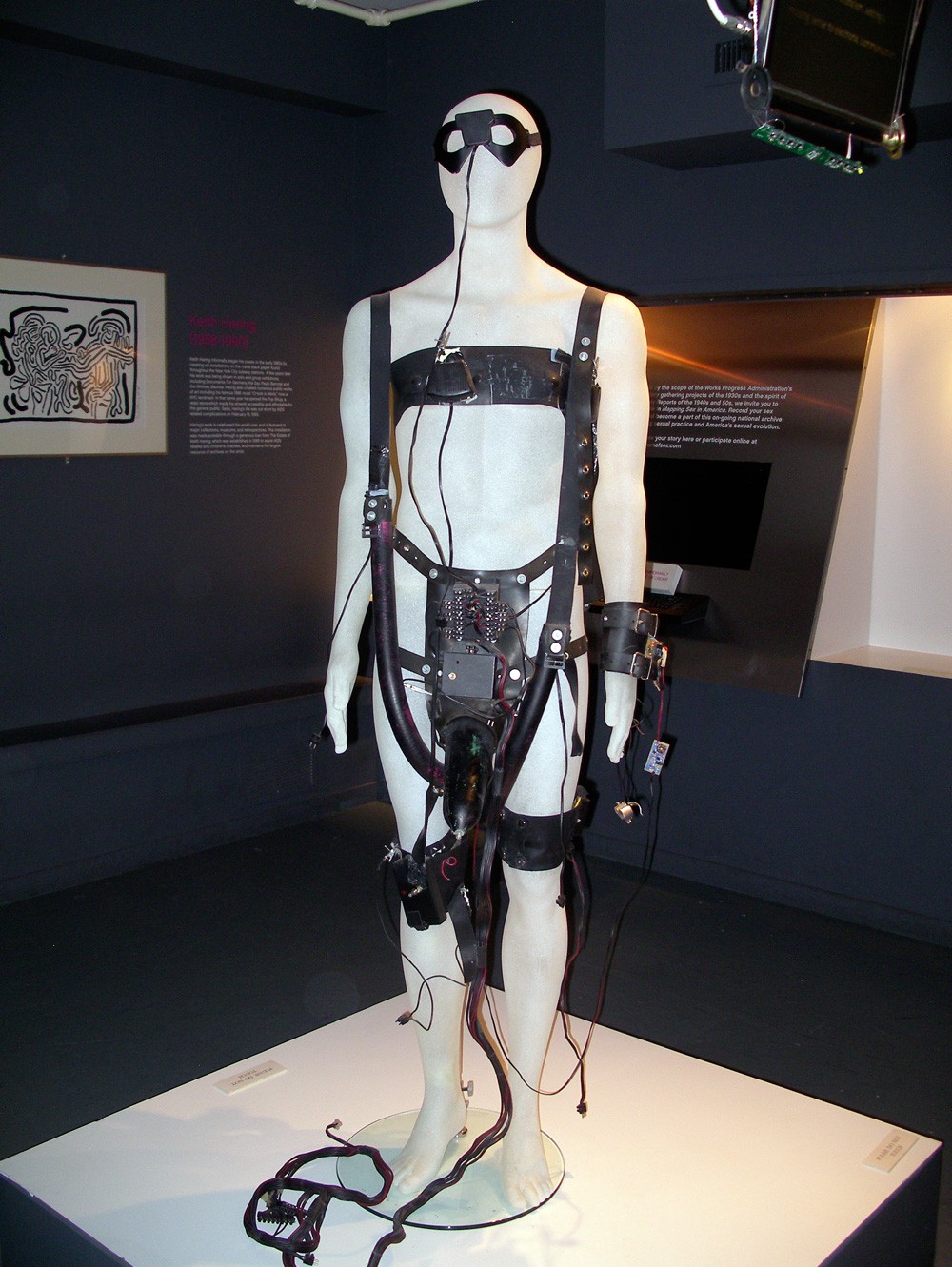

The risks of sex-toy hacking are intuitively dire given how inherently private sexual information is. But even experts can have a hard time pinning down specific vulnerabilities — high-tech sex toys are diverse in function and thus in the information or access they might provide. Demos like those by Trend Micro or the Def Con hackers have focused on a few vibrators, but teledildonics — the industry term for a wide variety of remote sex technologies — currently encompasses dozens of devices. They range from basic vibrators a partner can activate from afar to the high-end Kiiroo’s Onyx and Pearl, a vibrator and masturbation sleeve combo that connect to allow one to experience a distant partner’s actions in real-time. Theoretically, the toys of the future could even allow users to record every physical aspect of a sexual encounter, remote or proximate, and save it for replay or distribution.

As with any smart device, there’s the obvious risk that a company could opaquely collect and sell, or a hacker could illicitly siphon off, metadata on users. Think: the sort of stuff ostensibly gathered for market research, like when devices are being used and how. Last spring, a hacker known as Render Man launched The Internet of Dongs (a play on the industry term for smart device networks, the Internet of Things) to probe and detect security risks in sex toys. He explained how, in the wrong hands, innocuous data could reveal uncomfortable details. “Data about when a device is used,” for example, he said, “may be evidence of infidelity, as is who a user is connected or ‘paired’ with.”

Ken Munro of Pen Test Partners, a British security firm that’s dabbled in protective dildo hacking (yes), said he’s “much more concerned about the audio and video that is linked to these toys.” On April 3, the firm reported on a dildo with a WiFi-connected endoscopic camera that testers characterized as trivial to hack. “Sextortion is a growing problem around holding individuals to ransom over very personal videos,” he said, citing a spate of scams in recent years in which women target lonely men on Skype and get them to masturbate or talk dirty, record the session, and then demand payoffs to hold the content.

But the risk of extortion may be the least of it. Kyle “qDot” Machulis of the teledildonics blog Metafetish is much more concerned about the possible direct physical consequences of toy hacking. First, there’s what Render called “incredible stalking potential.” He and Future of Sex editor Jenna Owsianik both noted that the right security flaws may allow hackers to gather identifying details, like an email address, as well as geolocation data and an IP address. Then there’s the issue of long-distance sexual assault. Owsianik and Render believe there’s a real risk an outside party could activate individuals’ sex toys. If a toy goes off in a sock drawer, that’s one thing; if a hacker takes control of one in use, that’s completely another.

This type of cyber assault is especially concerning given how difficult it could be to prosecute. Provided a victim could even find someone to sue, Alice Vachss — an outspoken sex crimes prosecutor and public commentator — said you could certainly charge them with the unauthorized remote control of a device, which is a crime. However, she added, “sex toys have long been a prompt for victim judging,” meaning it could be difficult to get anyone to take the cases seriously enough to pursue them with force. And in many jurisdictions sex crimes cases, as opposed to lesser harassment charges, require proof of intent, which could be hard to prove with a hacker. Did they know a device was in use? Did they intend, by hacking, to derive sexual stimulation from or to assault the user?

It’s surprising a collective uproar over security issues didn’t come sooner. The concept of teledildonics has been around since 1975, the tech involved could have been realized in early and low-fi forms in the 1980s, and basic cyber-linked sex toys came onto the market in the 1990s. The wider sex toy industry started serious forays into teledildonics over a decade ago. Machulis started covering teledildonics in 2004, and security has been on his radar that entire time; Render started to explore the field a year later.

The wider public has had several years to adjust to the now-popular knowledge that any digitally connected device, like the Cinder grills, Nest thermostats, all-powerful Amazon Echoes, or any other number of products that have started to proliferate in many homes over the decade, can be hacked. Tech outlets were warning of systemic risks throughout smart device networks almost four years ago, and three years ago mainstream outlets started ringing alarm bells about industry reports that nearly three-fourths of all such devices were particularly vulnerable.

Consumers might be aware of general hacking risks, said Machulis, but they rarely remember to think about the sock drawer. Machulis thinks that’s because we’re so used to certain ways of thinking about sex toys — they’re walled off, clandestine, low-tech. The folks he talks to often know about phone sex or sexting, but they think about teledildonics like sex robots: something far off rather than an immediate reality. Even when users do become aware of threats to security through their digital devices, they can be bad about taking precautions. “There are a lot of people who know the problems and are like, ‘fuck it, I want to use it anyway,’” said Machulis.

According to Render, toy developers were until recently entirely hardware vendors, not used to dealing with software. On top of inexperience, the necessity of getting a product to market quickly while keeping development costs low disincentivizes agonizing over security. “They are genuinely and innocently ignorant of the threats they face until it bites them,” Render said.

For a long time, Render claimed, no one in the tech industry would take it upon themselves to investigate and tip producers off to security shortcomings because of the subject matter. “I have no dignity, so I have no problem with it,” he said. “I see a problem and I feel this compulsion to fix the risk.” So he got proactive about testing devices and alerting manufacturers to flaws a little less than a year ago. (For all his claims to dispassionate and analytic motives, Render will admit that it feels odd to “device job satisfaction from helping people masturbate each other safely… making my mother proud.”) But his one-man crusade was long a limited and low-profile venture. He believes that until last September’s We-Vibe lawsuit, most toy developers still had no idea of the risks they ran.

Although sex toys were a tiny and low-rent market for much of their considerable history, they started to gain in social acceptability in the late 1990s (props to “Sex and the City”). Now it’s an over-$15 billion industry, projected to hit $50 billion by 2020, with hundreds of thousands of toys available across the web and even in big-box stores. It’s hard to tell how much of that market is devoted to teledildonics, or how many connected sex toy users there are overall, but We-Vibe alone had two million registered users last fall. The economically ailing adult industry also feels intense pressure to move into and mainstream virtual reality porn and remote sex rigs as fast as possible to restore its profits. Innovators spurred on by the growing market for these devices are developing ever more immersive and thus invasive and risky products.

In recognition of the expanding number of smart toy users potentially at risk, the hackers behind the Def Con We-Vibe presentation launched the Private Play Accord, an initiative to create toy security protocols . Render claimed their hack validated his own probing around and gave him the shot in the arm to really get working on the Internet of Dongs. Since then, Pornhub — arguably the king of modern porn delivery and itself a potential teledildonics player — has signed on as a sponsor. They help Render acquire toys to test and back him as he approaches developers with notes and advice. His idea is for the project to turn into — in true hacker-culture form — a loose alliance of researchers, united in intent and concern, all collaborating to make modern masturbation safer.

The makers of We-Vibe didn’t respond to the Def Con presentation last summer, and responded to the lawsuit with pretty perfunctory statements. Even when they settled the suit for $3 million and agreed to destroy the data they’d collected this March, they admitted no wrongdoing. Munro said making people aware of risks often just leads developers to offload responsibility onto consumers in user agreements and notifications. But Render has been pleasantly surprised by the way the industry as a whole has reacted to his recent work. “Every single person I’ve talked to… has been supportive of [his white-hat hacking] and quickly realizes they need to get their act together,” he said, adding as an afterthought that, at the very least, no one’s sued him yet.

Machulis said he thinks this responsiveness is, at least in part, a manifestation of economic realities: The sex toy market is expanding, but it isn’t quite like big appliance or electronics firms yet. Most tiny, relatively young developers can’t take a huge monetary hit on a scandalous public lawsuit, or suffer terrible PR incidents. Machulis’s dream is that this vulnerability will push producers to hold all their future products to higher security standards. That would realize Render’s dream of security proactive enough that sextortion, stalking, and cyber-assisted rapes are always things we worry about in abstract, but never see in the headlines.

Not everyone in the adult industry takes hacking risks seriously yet. Ariana Rodriguez, who covers devices and innovations for the industry publication xBiz, said she believes “concerns about hacking sex toys are baseless,” because she is convinced the adult industry is built on privacy. But this reaction doesn’t recognize that a commitment to privacy doesn’t always mean you know how to achieve it — and that’s the problem.

In the We-Vibe lawsuit — the biggest public alert regarding toy security to date — Render believes there was no evidence of anything shady. The company essentially got slammed for not disclosing correctly what data it was collecting, but did not appear to be selling or compromising what limited data it did collect. The threat that case highlighted remained abstract to users, which is a problem as efforts like the Internet of Dongs will likely need popular support — i.e. clear indications that consumers will punish developers who fail to adequately address security issues with a firm blow to their bottom line — in order to push past the industry’s worst recalcitrance and ignorance. Hackers’ tips for consumers on how to secure their devices won’t go very far unless users are motivated to listen to or consult them.

Ultimately, security experts believe a high-profile security violation is imminent. Render says he’s waiting for the first divorce case tied to leaked device data or a major extortion scandal within a year or two, and suspects there could be a hacked toy assault case in the news within five years. Machulis “figured [a rape] would have already happened by now, honestly.” How severe the hack is and whether it will galvanize the industry or torpedo consumer confidence in the whole endeavor is entirely up in the air. It’s a strange Dildo of Damocles to have hanging over our heads, as an increasingly sexually explorative and comfortable culture. But at least the level of risk we expose ourselves to in a world of teledildonics is in our own hands.