Relive Your Favorite Childhood Fairy Tales With Ravel's 'Ma Mère l'Oye'

Folks, it’s spring. Maybe not where you are, but it is where I am, and that’s a thing to be excited for. I have a sunburn, for example, which feels new and exciting and unrelentingly pleasant, as least for now, until my skins falls off. Anyway, speaking of “unrelentingly pleasant,” remember our friend Maurice Ravel? In the mess of all of our moody and Romantic Germans, he was the French composer I spent 1,000 words trying to figure out if he fucks? (More or less: yes, he does.) Well, I want to return to him, and even earlier on in his career, to a piece of music that is tonally the opposite of Bolero. It’s his 1911 suite, Ma Mère l’Oye, or… [drumroll for an English translation] Mother Goose!

Now don’t get riled: I know this is music for children and this is a column for adults, but Ma Mère l’Oye is one of the most enchanting pieces I’ve had the delight of playing. Many of my high school and college playing experiences were vaguely traumatic, for one reason or another, but this is one that brings back only fond memories, which, who knows, maybe it’s just nostalgia talking. Ravel originally composed to the piece for children of his friends to play and enjoy — composers were always doing shit like this, it seems, meeting nice children and being like, “look, I wrote you a nice piece of music about childhood” — and then later adapted it from piano to orchestra to a full ballet. The recording we’re listening to this week is the full ballet by the New York Philharmonic in 1971.

It begins with a light and airy Prélude — equal parts sleepy woodwinds and muted fanfare. Think of it as all of the members of the orchestra waking up slowly, easing themselves into the universe of these nursery rhymes. From there, with a hearty and almost foreboding crescendo, it’s right into the Danse du rout et scène, or the Spinning wheel dance and scene. A dance and a scene? Jackpot, baby. And what a dance this is: bouncing flutes and clarinet, runs on the harp (there’s harp here!), even a little bit of snare drum to keep rhythm in parts. Now I know you’re thinking or asking or typing a rude comment on Medium dot com, “Fran, what the heck nursery rhyme or Mother Goose story is the spinning wheel?” Buddy, get it together: we’re talking, of course, about Sleeping Beauty, and the spinning wheel that she pricked her finger on. It’s the rush of the song that indicates she’s going too fast, not paying attention, all the while allowing herself to fall victim to her curse.

From there, it gets into our more traditional fairy tales and nursery rhymes. Pavane de la belle au bois dormant is, in fact, a pavane — a type of couple’s dance originating around the time of the Renaissance — of Sleeping Beauty. And it begins as such, with a flute solo that’s almost like the sound of trying to wake someone up quietly. The rest of this relatively short movement is meant to feel more abstract and dreamlike. It’s delicate and gentle, like a girl who was cursed to nap forever (I wish same). Halfway through, or, around the 1:32 mark, there’s a brief rest before a piccolo solo collides with the low brass to represent, well, a tumble, if you will, into the dream world of this story.

In Sleeping Beauty’s dream, depicted on stage during the ballet version of Ma Mère l’Oye, she witnesses Les entretiens de la belle et la bête, also known as Beauty and the Beast (very meta) who are “voiced” by the clarinet and the contrabassoon, respectively. This feels a little more reminiscent of our friend Prokofiev’s Romeo & Juliet, which really did have distinct instrumental voices within a ballet. The clarinet is self-assured, determined, relatively high-pitched but also not just wisping along like a flute. And the contrabassoon is, to be fair, a little scary! These two voices, or instruments, like in the movie with Emma Watson and the hot guy from The Guest, bicker back and forth, so much so that the full string section gets involved before finally agreeing to waltz with each other. With two fairy tales as familiar as Sleeping Beauty and Beauty and the Beast, it’s almost jarring not to hear the music we’ve grown so accustomed to backing it. This particular movement is tumultuous for a time, unsettling, as Beauty and the Beast once felt and seemed before the Beast got too hot.

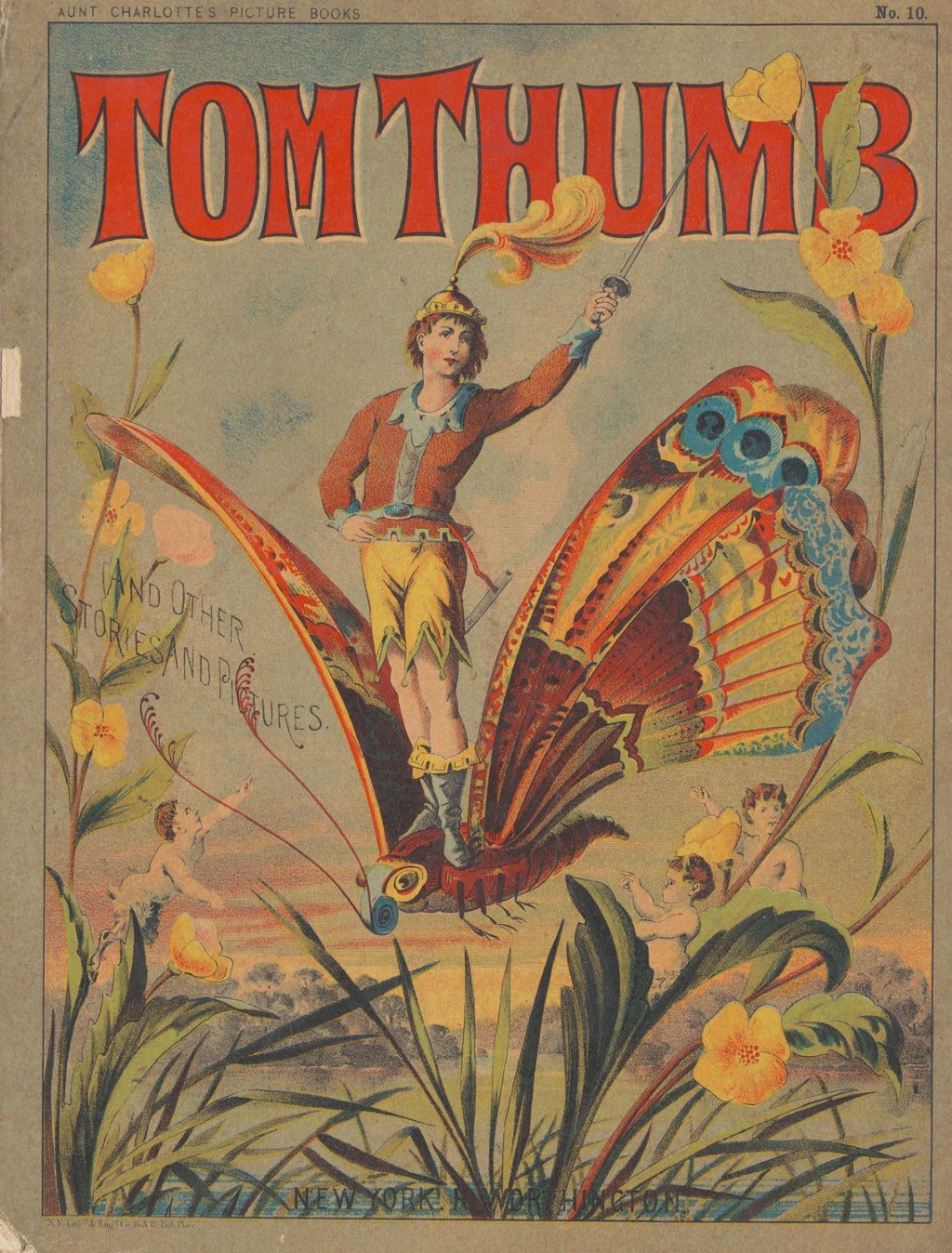

From there it goes into Petit Poucet, also known as Tom Thumb. Remember Tom Thumb? He, like so many men in the world who think they are interesting, is just a guy who so many things happen to. He’s getting swallowed by an animal, he’s fighting a giant, he falls over. In turn, this movement of Ma Mère l’Oye feels kind of meandering and slow. That’s not to outright say “if it’s about a man, I don’t care,” but as pleasant as it is, listening to it is like taking a walk and forgetting where you’re going. The meter’s all over the place and at any given time, we’re hearing from a whole host of instruments. It does, however, end on a note of pure bells: glockenspiel, xylophone, celesta, what have you. And from one percussionist to, well, a whole group of strangers online: that rules.

Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes, or Little ugly girl, Empress of the Pagodas is admittedly my favorite part of this suite, although I feel obligated to acknowledge that it’s not based on anything good or notable. It’s drawn from a fairy tale by Countess d’Aulnoy about “the Orient” at large — never a good thing — but a very common thing, annoyingly, during this time in history. In turn, it has that very canned, stereotypically “Pan Asian” feel to it (it’s suggested Ravel saw a Japanese exhibit at the Paris Exhibition some twenty years prior, but who knows if it stuck enough for him to be culturally responsible). And yet: I can’t help but get a kick out of it. Bright, deeply percussive, easily the most hummable and playful, it seems like Franbait in a lot of ways. I mean, will I ever be strong enough to look past a xylophone feature? Almost certainly not. Perhaps it’s the rich instrumentation of this particular movement that draws me to it. It’s Ravel stepping out of his comfort zone, even, to take his listener somewhere new. This late in the suite, it does feel like a true and genuine departure.

Ma Mère l’Oye concludes with Le jardin féerique — The fairy garden — a soft and somber close. Its opening melody feels borderline tragic, heavy with heartbreak, weighted with sorrow. It’s not that dire, certainly, but still, the fairy tales are over. Ma Mère l’Oye is a ballet, certainly, but beyond that it’s almost just a reprieve. It’s a fresh break in the middle of a long afternoon, a chance to stretch your legs and escape from your surroundings. Its end, complete with bells and whistles, literally, on top of a timpani-backed fanfare, is a triumphant and dazzling celebration of youth and imagination.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.