Prince's Female Mirrors

The Svengali and his muse.

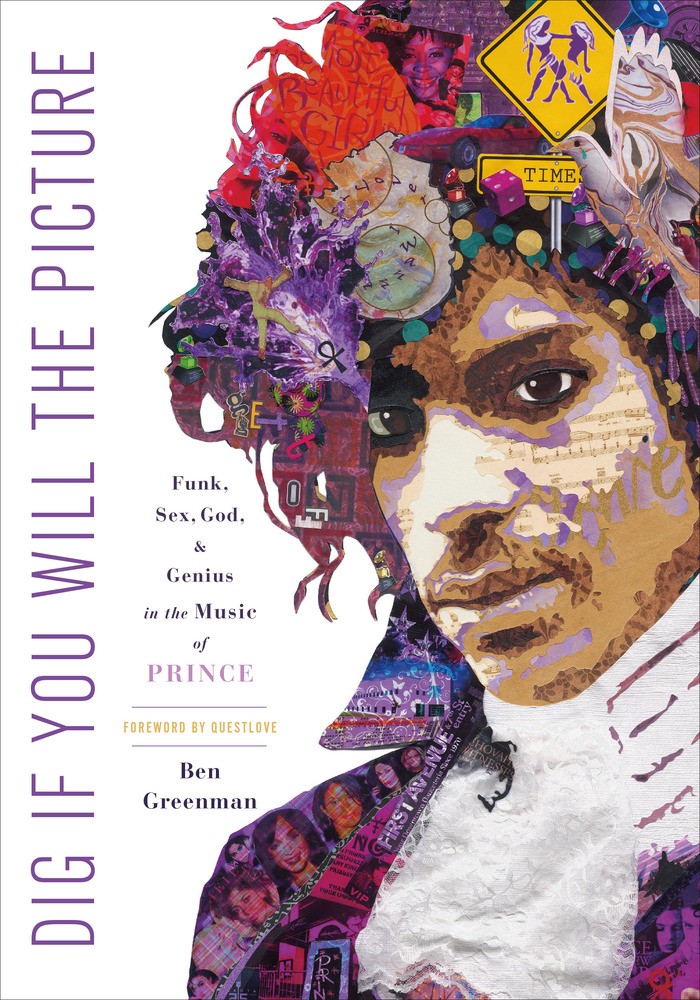

The following is excerpted from Ben Greenman’s forthcoming book-length study of Prince, Dig If You Will The Picture (Henry Holt), set to be published on April 11.

In pop music, female artists are often controlled by male artists — they are given songs to sing, costumes to wear, sometimes even new names to replace their real names. There’s a long tradition of this, or rather, two of them: the Pygmalion tradition on one hand and the Svengali tradition on the other. Pygmalion stories, which began in Ovid and crystallized into their modern formulation in George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 comedy of the same name, usually end with the older male figure falling in love with his protégée. Svengali stories, rooted in George du Maurier’s 1895 novel Trilby, tended to be more exploitative and predatory: du Maurier’s own illustrations depicted the character as a spider in a web, trapping and devouring his prey. Historically, the music industry has lent itself more to the latter model. Rebecca Haithcoat, writing in Vice Media’s Broadly just a few weeks before Prince died, explored the history of the male Svengali in pop music, from Phil Spector to Kim Fowley, with a special emphasis on the economics of the arrangement. Women were permitted to write and perform songs, while men tended to occupy producer roles, in large part because production was needed (and compensated) whether or not songs were released. Similarly, upward mobility was distributed unevenly among the sexes; women had plenty of male mentors (older industry figures who helped them find their way to more work) but not nearly as many male sponsors (older industry figures who taught those younger women how to create work themselves). In these terms, Prince was a Svengali, though his special relationship with female identity ensured that he was just as snared in the web.

Backstage at the American Music Awards, he met a young model and actress named Denise Matthews. Matthews, in her early twenties, had been born on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, the product of an ethnic crazy quilt that included Afro-Canadian, Native American, Hawaiian, Polish, German, and Jewish blood. She had gone to New York to model, but she was too short, and an agent suggested Los Angeles and acting roles instead. She found some, including a small part in Terror Train (a slasher film set aboard a moving train that starred Jamie Lee Curtis) and a larger one in Tanya’s Island (a romantic adventure, of a sort, about a castaway juggling relationships with both her brother and an ape-man). In both films, Matthews was billed as “D. D. Winters.” In neither film was she especially memorable.

But she made an impression on Prince. The two of them began a relationship, and when he returned to Minneapolis, he invited her to come stay with him. Once she arrived, he began to involve her in a new idea he had — a highly sexualized girl group performing songs he would create especially for them. The initial incarnation of the group, called the Hookers, was built around Susan Moonsie, a friend of Prince’s from high school. The Hookers petered out around the time of Controversy, but Prince revisited the concept with Denise, who he felt would be a perfect frontwoman for the band. He tried to convince her to change her name to Vagina. She refused, understandably. They compromised on Vanity.

The name had at least two meanings, both perfect: Prince liked to think of Vanity as his female mirror image, and she was also about to become the center of his first true vanity project (though you could make the argument that Morris Day, with his mirror, was also all about vanity). Vanity, Susan Moonsie, and a third singer, Brenda Bennett, entered the recording studio in March of 1982 to add vocals to a set of tracks that Prince had already prepared. Five months later, Vanity 6 released its debut. “Nasty Girl,” the opening song, established the formula: spare synthpop grooves, mostly friendly, with salacious lyrics and vocals that were more coy than powerful. “Do you think I’m a nasty girl?” Vanity asked, and answered a few lines later: “I need seven inches or more/ Get it up, get it up — I can’t wait anymore.”* Elsewhere on the record, Prince gave the band more outré electronics (“Drive Me Wild,” “Make-Up”), risqué songs (“Bite the Beat,” a celebration of oral sex which could have been handed off to Blondie or the Go-Go’s), and relatively innocent songs with risqué titles (“Wet Dream”). The ballad “3 x 2 = 6” had an attractive melody, but it exposed Vanity’s limitations as a vocalist. The funkiest, funniest moment was the Time-like “If a Girl Answers (Don’t Hang Up),” a skit-song combo in which Vanity tangled with the new girlfriend of an ex (played, hilariously and unconvincingly, by Prince).

Vanity 6 ran its course — or rather, ran off course. Vanity was cast as the romantic lead in Purple Rain but departed before shooting started. Replacement auditions for the film were hastily arranged. The part went to Patricia Kotero, a Mexican-American model and actress who had had appeared in various television shows and a few music videos, including Ray Parker Jr.’s “The Other Woman.” Prince renamed her Apollonia — this time, he only had to look as far as her middle name — and cast her in both the film and a new version of Vanity 6. Apollonia 6 featured mostly Kotero and Brenda Bennett, along with backing vocals by Lisa Coleman and Jill Jones. Though Apollonia was a better singer than Vanity, the music had little of the punkish insistence of its antecedent. The songs were more fully realized, which ironically worked to their disadvantage — mostly they just sounded like less energetic Prince songs, and in fact several tracks demoed by Apollonia 6 and left off the album ultimately entered the Prince canon via other routes: “Manic Monday” (which ended up with the Bangles), “The Glamorous Life” (which found a home with Sheila E.), and “17 Days” (which became the B side of “When Doves Cry”). The two keepers were “Sex Shooter,” a close cousin of “17 Days” that the band performed onscreen in Purple Rain, and “Happy Birthday, Mr. Christian,” which reversed the plot of the Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” and added a deadbeat-dad twist: Mr. Christian, the high school principal, impregnated a student but wouldn’t support her and her child. Apollonia left after the band’s sole album.