The Hero And The Crocodile

Flawed historical figures and who can claim them.

The real-life inspiration for the character Mick “Crocodile” Dundee, played by Paul Hogan in the Crocodile Dundee series of films, is commonly cited as Rod Ansell, an Australian bush tracker and catcher of wild buffalo made famous as a survivalist when he was stranded in the Outback for two months in 1977. Though repeatedly denied by Hogan, elements of the films seem clearly based on Ansell’s media appearances. When Ansell died in 1999, he was eulogized by the press as “the real Crocodile Dundee.” Yet ask anyone in Latvia, and they’ll tell you that the character was really based on a man nicknamed Crocodile Harry.

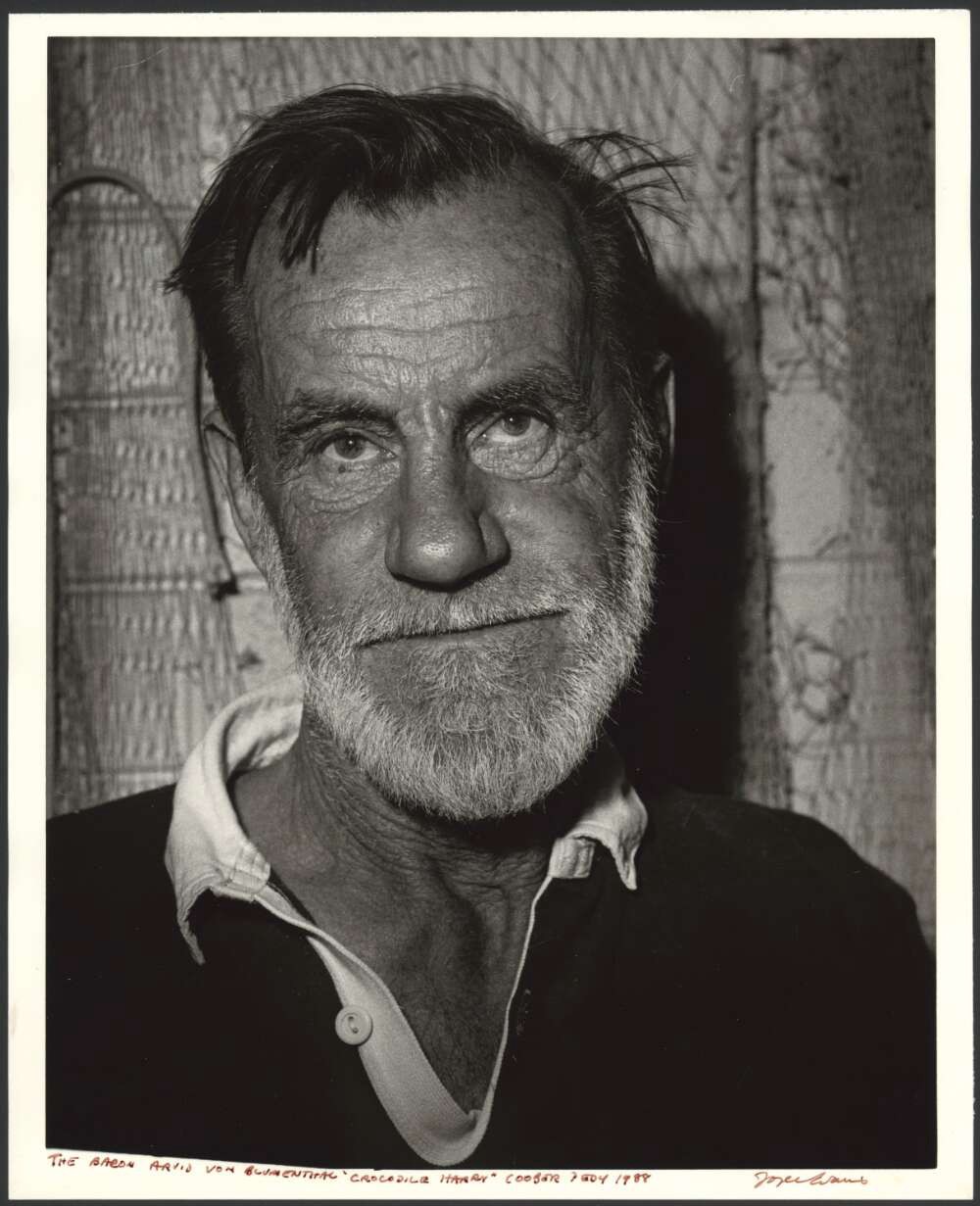

In Queensland and the Northern Territory of Australia, Crocodile Harry hunted and killed a claimed 10,000 crocodiles (in some accounts it was 40,000!) over 13 years in the 1950s and 1960s, until the practice was outlawed. Undaunted by the restrictions, he took up surveying before settling in to the mining town of Coober Pedy, where he made a living as an opal miner. Living in a hillside dugout he called the Crocodile’s Nest — a home so bizarre it was used to film a scene in Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome — Crocodile Harry quickly became a local legend. He charged admission to visit his home and told the Australian press that he was Arvid von Blumenthal, an exiled baron from a noble Baltic German family in Latvia.

A notorious womanizer, Crocodile Harry was also known for keeping bras and panties in the Nest as trophies of his sexual conquests. In his older years, he seems to have settled down a bit, marrying a German singer named Marta and spending his days sculpting. Obituaries announcing his death in 2006 celebrated him as Latvia’s crocodile hunter and the inspiration for Crocodile Dundee; since then, the legend of Crocodile Harry has continued to make the rounds as a bit of trivia in both Latvian and Australian blogs and media outlets.

In reality, the self-styled Baltic baron was a Latvian named Arvīds Blūmentāls, born on a farm near the village of Dundaga in 1925. Having won its independence after World War I, Latvia was an independent country from 1918 to 1940, at which time it was occupied by the Soviet Union; a Nazi German occupation followed in July of 1941. At age 17, Blūmentāls dropped out of school and volunteered for the German auxiliary police, lying to recruiters that he was 18 years old. In Ukraine, he served with the 25th Abava Battalion, known by locals as the “green devils,” for both their tenacity and the color of their uniforms.

In 1943, he was transferred to the Latvian Legion, a regular combat unit in the German Waffen-SS. After a two-year long retreat westward, the remnants of his unit ended up near Berlin, where in April of 1945, he and some comrades tore off their SS insignia and tried to escape. With the help of a Latvian doctor, he removed the Waffen-SS blood group tattoo on his arm and told Allied authorities he had been a forced laborer in Germany, to avoid becoming a prisoner of war. Along with about 200 other Latvian Legion veterans, Blūmentāls joined the French Foreign Legion in 1947 and served for several years before coming to Australia.

Though Blūmentāls joined the auxiliary police too late to have been a Holocaust perpetrator, he almost certainly served with men who were. Some volunteers were ideologues or opportunists, but the evidence points to Blūmentāls as a mercenary adventurer, who sought escape from the drudgery of farm work and country living. Despite this complicated history, he is celebrated in Dundaga as its native son and local hero. A statue of a crocodile has been erected in his honor near the medieval castle at the center of town; inside the castle, visitors can view a permanent exhibition celebrating Blūmentāls’s life and career. Recognized nationwide for his exploits thanks to books, news articles, and a 1995 documentary film, Krokodilu Harijs (as he is known in Latvian) remains a source of pride rather than embarrassment.

Building a pantheon of notable historical figures for a country might seem like a straightforward process. But in the borderlands of Central and Eastern Europe — characterized historically by shifting imperial borders and ethno-religious diversity — questions of ownership arise. Was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart the great German composer or the great Austrian composer? Similarly, Adam Mickiewicz is claimed simultaneously by Poland and Lithuania as their national poet. Mickiewicz opened his epic poem Pan Tadeusz with, “Lithuania! My fatherland! You are like Health! Only he who has lost you knows your true worth,” words that inspire Lithuanian patriots to this day. But it must be remembered that Mickiewicz wrote that line in Polish and did not speak a word of Lithuanian — he was celebrating a very different Lithuania than the modern nation-state that emerged in the twentieth century.

Ambiguous ownership is one thing, but the mixed populations of the borderlands can also mean that one group’s hero is another’s villain. For leading an uprising in 1648 against Poland that established an independent Cossack state, Bohdan Khmelnytsky is considered a national hero in Ukraine and has been honored with place names, statues, and his portrait on Ukrainian banknotes. However, the participants in Khmelnytsky’s Uprising also massacred thousands of Jews, which left a lasting impact on Jewish collective consciousness in Eastern Europe. An annual fasting day was observed for centuries by the Jewish authorities in Poland to commemorate the “calamities” and their martyrs, while prominent Jewish historians like Simon Dubnow referred to the uprising as the “Ukrainian Catastrophe,” an event not matched in his mind until the pogroms and mass murder of the twentieth century.

Latvia, subjected to some form of imperial rule or foreign occupation for 752 out of the last 800 years, is a quintessential country of this borderlands region. It is under these circumstances that Latvians have cast a wide net in searching for figures to represent their nation, reaching as far away as the Australian Outback as well as dredging up some unsavory characters closer to home.

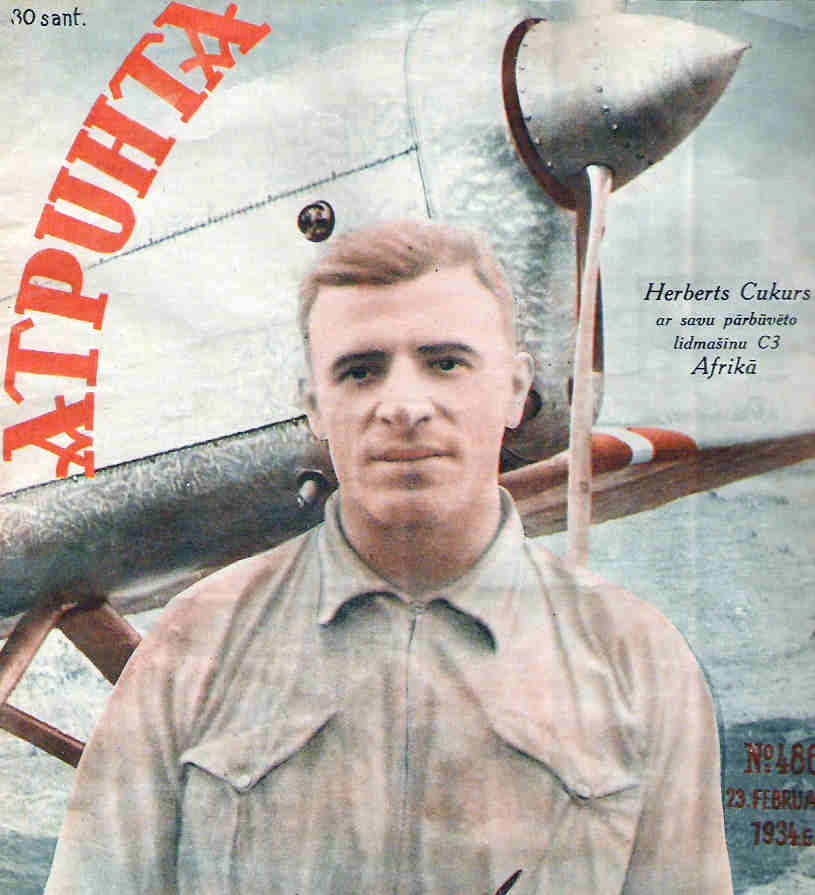

Arvīds Blūmentāls is not alone as a deeply flawed Latvian hero — take Herberts Cukurs, for example. A pioneering aviator in the mold of Charles Lindbergh, Cukurs made record-breaking long-distance flights from Latvia to both the Gambia and Japan. Like Lindbergh, Cukurs’s reputation would later be sullied by his activities in World War II. During the German occupation, Cukurs served as the right-hand man of Viktors Arājs, the leader of an anti-Jewish killing squad responsible for tens of thousands of deaths. As the war ended, Cukurs escaped to Brazil, where he worked as a pilot. But having been one of the most famous people in Latvia, he was recognized and identified by Jewish survivors, and in 1965, he was lured to Uruguay and assassinated by the Israeli intelligence service, Mossad. Yet despite his involvement in the Holocaust, Cukurs remains a relatively beloved, if controversial historical figure. In defiance of his fatal flaws as a hero, artistic works — including a novel, Flesh-Coloured Dominoes by Zigmunds Skujiņš, and a musical, Cukurs, Herbert Cukurs — have presented him as a rescuer, rather than murderer of Jews. This strange and cynical inversion of history is condemned by academics and Jewish organizations across the world, but such objections are inevitably shrugged off by Cukurs’s admirers.

In refusing to categorically repudiate historical figures with ties to the Nazi German occupation and the Holocaust, Latvia is not alone in the borderlands of Europe. In neighboring Lithuania, “not a single Lithuanian sat one day in jail” for atrocities committed in collaboration with Nazi Germany, while nonagenarian former Jewish partisans are still pursued by prosecutors for their alleged war crimes. In Ukraine, the state-sponsored rehabilitation of Ukrainian nationalists who inspired or took part in the massacre of thousands of Jews and Poles during the war has raised tensions with Poland, Russia, and Israel.

But Latvia is perhaps unique for combining endearment for violently nationalist figures with public pride for cosmopolitan members of minority groups who also happened to live in Latvia. Along with some famous Germans who lived temporarily in Riga like the composer Richard Wagner, the Latvian Jewish community has produced some of the most internationally recognized figures with connections to Latvia. Filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein and philosopher Isaiah Berlin were both born in the present-day Latvian capital of Riga, while Mark Rothko was born in the city of Daugavpils, located in eastern Latvia. Today, the Latvian state seeks to claim them as its representatives, with an exhibition, a commemorative day, and a museum dedicated to Eisenstein, Berlin, and Rothko, respectively. But these three men all emigrated relatively early in their lives and none of them felt any particular attachment to Latvia thereafter. Furthermore, as Jews, had these men remained in Latvia, they almost certainly would have died in the Holocaust, most likely killed by someone like Blūmentāls; it feels somewhat absurd to place them all together in lists of “famous Latvians.”

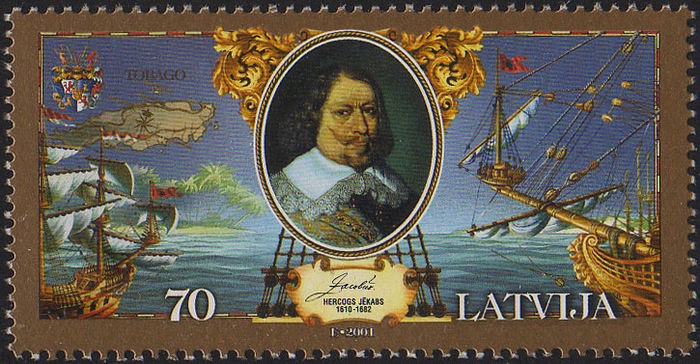

Controversies over World War II in Latvia occupy the most ink and airtime internationally, but “Nazis” (Latvian historians eagerly point out non-Germans couldn’t be Nazi Party members) are not the only bugbears to be found; earlier figures present problems of veneration. Blūmentāls’s hometown of Dundaga was ruled in the seventeenth century by Jakob von Kettler, the Duke of Courland and Semigallia. Duke James — as he was known in English — became the ruler of Europe’s smallest colonial power, when he founded New Courland and its capital city Jamestown (in German, Jacobusstadt) on the Caribbean island of Tobago. He also established a trading post at the mouth of the river Gambia in Africa. In search of a usable past, Latvians tend to venerate the Duke — a Baltic German who likely felt more connected to the royal courts and universities of Germany than the Latvians over which he ruled — as a good ruler and the founder of a “Latvian” colonial empire. But the wealth that flowed from the colonies back to Latvia was predicated on slave labor; the fort and trading post served as a holding pen, where kidnapped Africans were placed in chains to await their shipment to the Americas as slaves.

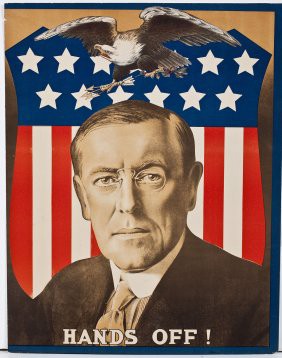

Historically, North Americans and Western Europeans have assumed a (baseless) sense of moral superiority over Eastern Europeans. The American Founding Fathers preached liberty while they owned slaves, and European colonialism was as bloody and brutish as the totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century so universally condemned today. A number of American historical figures have recently been subjected to public reevaluation. After months of obstinacy, Yale University finally decided in February to rename Calhoun College — honoring the intellectual godfather of secessionism and staunch defender of slave power, John C. Calhoun — to commemorate Grace Murray Hopper, a mathematician and pioneering computer programmer who ended her career as a U.S. Navy admiral. At Princeton University, students began a campaign in 2015 to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from campus buildings and the university’s school of public policy. Wilson served as president of both Princeton and the United States, but has faced renewed scrutiny for his racist views and support for segregation.

If the topic of colonialism is not deeply tainted in Latvia, on Tobago itself the colonial encounter was distant and brief enough that Latvian tourists to the island are purely an object of curiosity or bemusement, rather than scorn. In other postcolonial states and the former colonial metropoles in Europe, this is not the case. A movement called “Rhodes Must Fall” has emerged in South Africa that seeks to remove statues and symbols of Cecil Rhodes from universities there. As the architect of British colonialism in Africa, a believer in the racial supremacy of Anglo-Saxons, and perceived as a facilitator of the apartheid system that would emerge after his death, Rhodes is considered an intolerable symbol of colonialism and white supremacy in post-apartheid South Africa. After successfully toppling a statue of Rhodes at the University of Cape Town, Rhodes Must Fall spread to Oxford University, where another statue of Rhodes has become a target, though for now it remains standing. Since some of the South African anti-Rhodes activists responsible for spreading the movement to Oxford are beneficiaries of the eponymous Scholarship, a favorite tactic of their critics has been to accuse protestors of ingratitude or hypocrisy, rather than try to understand the basis of their critique.

Which legacy to emphasize when remembering a historical figure is, of course, a matter of perspective. For his support of national self-determination, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson was a revered figure in Central and Eastern Europe between the World Wars. In The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson, another former president, Herbert Hoover, recalls that the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 was met with elation in the cities of Latvia, with delegations bearing messages of gratitude meant for President Wilson and Latvian musicians playing “Yankee Doodle” as they paraded.

If he is remembered at all today in Latvia, Wilson would be thought of as a hero. But to celebrate Wilson the liberal internationalist and ignore Wilson the white supremacist is no longer viable among Americans who have absorbed developments in historiography and recognize the continuities between Jim Crow a century ago and systemic racism today. In every case, these historical reevaluations will be met with references to babies and bathwater, but they serve as a reminder that history is not an unchanging canon. Emerging from the same universities once attended and patronized by these men, what these parallel movements reflect is current historical scholarship and discourse — not anti-intellectual and immature manifestations of student protest gone wrong, as often painted by their critics.

Despite the obstacles presented by academia and the general public’s attachment to romantic nationalist versions of history in the Baltic States, the impulse to aggressively and publicly challenge prominent historical figures is not entirely absent there. The author Rūta Vanagaitė became interested in coming to terms with the murder of Lithuanian Jews by their gentile neighbors under the German occupation. To do so, she teamed up with the “Nazi hunter” Efraim Zuroff and traveled across Lithuania, producing the book, Our People: Journey With an Enemy. Crucially, Vanagaitė exposed her own grandfather — a man celebrated for his role in the protest movement that eventually restored Lithuanian independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 — as a collaborator who compiled lists of Jews for the Germans to detain and murder.

Against accusations that she is a Russian provocateur or a closeted Jew, Vanagaitė insists instead that “a mature nation must know its history so it is not repeated.” Across the Atlantic, another woman with both Lithuanian and Jewish heritage has come forward with a similar story. In A Guest at the Shooters’ Banquet: My Grandfather’s SS Past, My Jewish Family, A Search for the Truth, Rita Gabis recalls her grandfather as a man respected in the Lithuanian-American community for opposing the Soviet Union as a partisan. But it is later revealed that he had also served as a local chief of the German occupation’s Security Police, with archival documents uncovering his role in arresting Jews and managing the local ghetto. Taking on the cherished notions of nationalist historical narratives is in many ways like being open and honest about complex and distasteful elements of family history — it takes courage, clarity of purpose, careful research, and the ability to connect the particular with the general. As Gabis puts it, with a simplified nationalist narrative populated only by heroic caricatures, “you lose complexity and texture, and the opportunity to be challenged or to grow.”

Next year, Latvia will celebrate the centennial of its declaration of independence; already, Latvians are searching for new or heretofore underappreciated figures to represent their nation. The preoccupations of the generation of Latvian World War II refugees — opposing the Soviet Union and its occupation of Latvia in the context of the Cold War and responding aggressively to any accusations about their own culpability during the war — and the fears during the 1990s of an isolated, vulnerable Latvia seem ever more distant. Tensions with Russia aside, Latvia today is a full member of the European Union and NATO and feels more and more like a cohesive nation-state as many of the children and grandchildren of Russian immigrants reach adulthood with fluency in Latvian and pride in their country. The further we move into the twenty-first century, the more Latvian history will likely look differently to its citizens. And someday soon, celebrating a man like Arvīds Blūmentāls might appear as absurd as hunting for crocodiles in the snows of Latvia.

Harry Merritt is a Ph.D. Candidate in History at Brown University.