The Bare "Bones"

Watching every episode of FOX’s corpse-focused crime procedural

On Tuesday, March 28, the television show “Bones” will take its final bow, capping off a historic 12-year run as one of television’s more successful procedural dramas, and a 12-year run as an all-in-one punchline. The show is about a forensic anthropologist who studies skeletons to help the F.B.I. solve murders—crimes that often produce at least one partial or whole skeleton. Thus, bones.

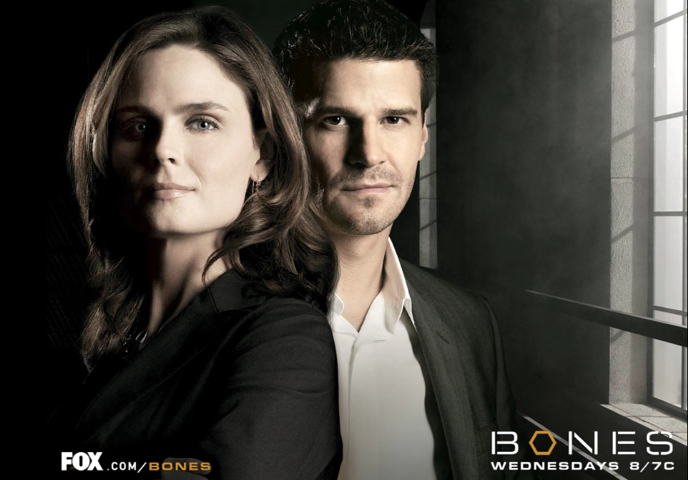

Bones. What a funny word! That’s a funny name for a show! “You watching ‘Bones?’” “Absolutely, love that ‘Bones.’ Got so many ‘Bones’ on the DVR.” The titular “Bones” is not just the skeleton rocks, but the nickname of Dr. Temperance Brennan, the shows central hero who, despite her name is not transplanted from the 1930s. Bones is joined by FBI Special Agent Seeley Booth, which also sounds like a name from the ’30s (he is also, and I am not making this up, a descendant of the same Booth clan as John Wilkes Booth).

Here’s the thing: “Bones” rules. It’s so goddamn good, and it’s a perfect antidote to the often overhyped “Golden Age of Television” (plodding prestige dramas and dramedies that do 10-episode seasons) and a relic of the era before “Peak TV” (too many television programs to choose from).

Bones is a scientific genius who scans as “near-autistic” — unable to understand sarcasm or jokes or actions dictated by emotion over logic. Booth, on the other hand, is a grizzled war veteran with strong religious faith and a more solid understanding of people’s ability to act against their own self-interest. Somehow, these two crazy kids managed to get together and start a family.

They are aided by a cast of characters that Booth refers to as “squints” — lab technicians at the fictional Jeffersonian Institute that help the F.B.I. solve gruesome murders. It is never really established why the F.B.I. has jurisdiction in most of these cases. Also, I forget why he calls them squints. Maybe it was slang 12 years ago.

This includes no-nonsense lab director Cam Saroyan, kinda gross but socially competent weirdo Jack Hodgins, and Angela Montenegro, who is the show’s tech person (the latter two eventually get married). They are joined by a rotating cast of interns—whoever’s personality is most relevant to that episode’s themes.

Here is how every episode of “Bones” goes: a body is discovered in a slapstick, grisly faction, usually decaying the woods or in a bath of liquefied human tissue. The Bones crew is called in to investigation, using the bones to figure out who the victim is, what they look like, and how they died. Booth and Brennan have some sort of spirited debate over that episode’s theme, and the complicated life of their victim, and make up by the end of it. During some episodes, they have to dress up in disguise and do terrible accents (“Bones” absolutely loves putting its leads in disguises. Why a non-government contractor is doing fields ops is never effectively justified). This is all par for the course for a network procedural.

I have a weird fascination with this ubiquitous but often unacknowledged part of the television universe. I can respect someone plotting out a tight 13-episode season, but one could argue it takes even more skill to create a premise and characters that can be stretched like silly putty for years and still retain its general contours. “Bones” has never really changed — neither the premise or its core cast of characters. One thing that I have to believe is that, given how heavily syndicated the show is, all of them are set, money-wise, for a few lifetimes. By this metric, it is possible that Emily Deschanel is more financially secure than her more famous sister, Zooey. (This is speculation, I do not know what the “Bones” cast makes re: syndication rights.)

That the “Bones” cast is made up of, I assume, very wealthy C-list actors is part of my minor obsession with it. These people have been on network TV for 12 years and yet I’d wager that the only household name is David Boreanaz (best known as Angel from “Buffy The Vampire Slayer”), an actor whose very existence as a famous actor became a punchline on “BoJack Horseman.”

Often underrated in “Bones” discussion is the fact that “Bones” is one of most disgusting shows on TV, which is probably its distinguishing feature. Bodies explode or slither, often people that discover the bodies do so by coming into veeerrry close contact with them. Guts and offal fly and spill and wiggle all over the place. The show is no less gory than “The Walking Dead,” the crucial difference being that “Bones” is played for laughs. “Bones” is heavy on the slapstick gore — quippy and cute even as it is crazy bloody.

It’s difficult to explain the appeal of “Bones,” but for me it is a reaction to the way the we laud most TV — the kind that results in 2-month seasons, or television that spends a year and a half off the air before returning for another 8-episode romp. It is easy (for lack of a better word) to be brilliant and dependable in short spurts. It’s a much more difficult tightrope walk to maintain consistency even as cultural zeitgeists change. “True Detective” took the gross murder mystery into meandering, freshman philosophy territory about man’s nature. “Bones” has always asked tougher questions, like “what’s the grossest way for somebody’s guts to spray everywhere?” “Bones,” from the jump, has always been reliably “Bones.”

The television criticism economy tends to look down on shows that stick around for a long time, equating such tenure with overstaying one’s welcome. For many shows, this is true — “Two and a Half Men” lasted for multiple seasons after one of the men (40 percent of the show) dropped out for reason of insanity; “The Simpsons” has coasted on its unrepeatable highs for more than a decade. But “Bones” has adhered to a formula almost out-of-time. Lab tech Angela’s computer models, with facial reconstruction and physics simulations constructed via a few taps on a tablet, were the right level of outlandish police tech in 2006, and now merely rate as slightly implausible.

And yet even as its characters remain in stasis — Bones is still too logical, Booth is still too skeptical — they follow standard arcs. They get married, they have kids, they suffer life-changing injuries that test their resolve, certain secondary characters die in tragic fashion. They move forward even as their central characteristics remain immovable.

This has been standard for as long as television has been around, and arguably since the radio soap operas of the early 20th century, and serialized novels before that. What I mean is that at some point, you watch a show for long enough that its quality becomes irrelevant (I watched all six seasons of Glee and I still can’t say why. Same with Girls). You’ve spent years watching characters progress; so long that the routine feels important, even if the actual storytelling is simplistic, or even falls flat. This is much easier to do with procedural or sitcoms than serialized dramas, but the principle still holds. At some point, they become part of your actual life routine, not just a thing that you occasionally enjoy.

If you need me to put it in prestige terms, “Bones” is one and a half “Mad Mens,” year-wise, and nearly 3 “Mad Mens” by episode count. Twelve years of “Bones” is almost half of my life. In high school, in the winter of 2009, we went on a senior trip to some “resort” in upstate New York. If I recall correctly, while most of my friends were outside smoking in a playground shaped like a pirate ship, I was hanging out with my English teacher talking about the “grave digger” subplot of “Bones.” Since then I’ve gone to college, been through multiple jobs, and the entire way, “Bones” has been on the air, providing serviceable entertainment, with new episodes and in syndication on the laundromat TV.

I watched the “Bones.” We don’t respect that enough.