Copland's 'Rodeo' Is An All-American Treat

Classical Music Hour with Fran

I, like presumably everyone else in the world, am in the midst of a rewatch of all of the Fast & Furious movies. This past Friday, I rewatched the 2011 classic Fast Five (the best in the franchise), and I was struck by a line said by Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. Some random operative in the military is talking to The Rock’s character, and he says the classic movie line of, “Good news, bad news.”

Without missing a beat, The Rock goes, “You know I like my dessert first.” And once the good news has been delivered, The Rock demands, “Gimme the damn veggies.” All of these lines might sound like a wild non sequitur for this column and/or a shameless plug to watch or rewatch Fast Five (you should), but they also made me realize that going a month on Brahms-related material was truly like a month of veggies. A month of damn veggies. That’s not to say Brahms and the Schumanns and Wagner aren’t all enjoyable — they are! — but like roasted cauliflower, you kinda gotta know what you’re working with. And even though I actually have not yet managed to finish my book, to quote what I’m sure is said in some other movie, “It’s time to move on.”

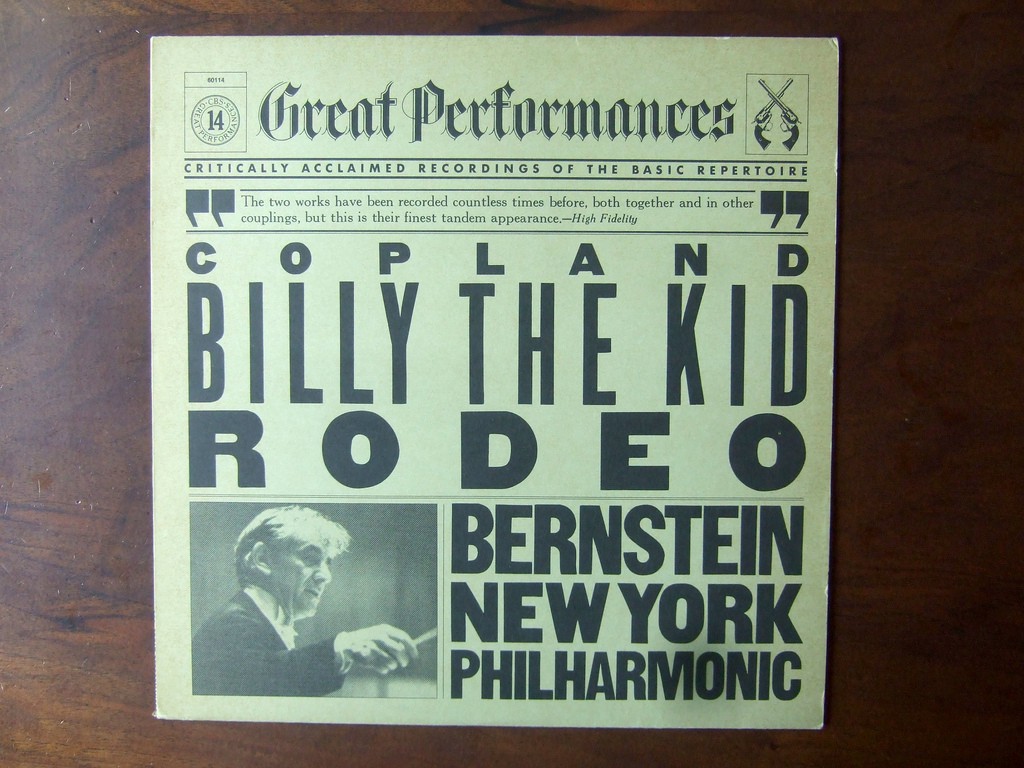

So this week I’m writing about full dessert. This is, like, some brownie sundae shit, I kid you not. This week, I want to bring you Aaron Copland’s 1942 Rodeo ballet (a 2013 recording by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra directed by Slatkin; I know it’s not Bernstein, I know). Aaron Copland, as his name may suggest, was a 20th-century American composer. While it’s Dvořák whom we credit, perhaps, with the invention of an “American sound,” Copland perfected it. Anything you think of as being purely American — cowboys, big wide plains, imperialism, you name it — Copland has a tune for it. While our German pals from the last month were busy fighting each other about the future and meaning of music — what made it good, what made it pure — Copland was a little more focused on bringing music to people. He was a populist. His work is easy to listen to on purpose.

So: Rodeo. This is pure Americana. I don’t care who you are or where you’re from; Rodeo is going to rile you up. It’s going to make you feel good. The 1942 ballet doesn’t sound particularly like any of the ballets we’ve previously looked at, and that’s okay. It does have a fairly standard ballet plot, if you will: a female lead known as The Cowgirl is forced to compete against other girls for the love of the Champion Roper. If this doesn’t sound like what every day in America is like, then you and I have different lives, my friend.

The opening movement is called Buckaroo Holiday and it rules. I mean, crash of the cymbals, fanfare, all that jazz. It pulls you directly in. All of the movements in Rodeo have a distinct southwestern American sound to them, clearly drawing on folk music from the American west. This movement also has one of my hands-down favorite sections of any classical piece I’ve ever heard. It’s borderline funny. Even if you listen to nothing else, cue up Buckaroo Holiday and go right to that 3:18 mark. You’re going to hear a back and forth between the cellos and basses, and the bassoon. It’s almost as if the bassoon is trying to coax something forward and then: at 3:32, we got one of the most de-fucking-lightful trombone solos in the history of music. I mean listen to that crescendo at 3:39. It’s SO GREAT. I laugh every time. Finally… it is the trombone’s time to shine.

The second movement is the Corral Nocturne, a sweet and quiet piece only about 4 minutes long. (Even the longest of the movements, Buckaroo Holiday is only about 8 minutes; there are no 20-minute-long movements here because this is music for the people, remember? It was World War II. No one had 20 minutes.) This nocturne is a very string-heavy tone poem. It’s hard to key into any particular part of it; it’s such a fully complete ballad. It hems and haws, like an August night out on someone’s porch, which is very effective after the maniacal energy of Buckaroo Holiday.

Now, the reason I went with the Detroit recording versus a more established one (e.g. Bernstein conducting in the 1960s, a CD I actually purchased in high school) is that it includes the third movement, often left out of symphonic renditions of Rodeo. That third movement is called Ranch House Party — I’m not kidding — and after the calming conclusion to Corral Nocturne, this piano introduction comes in like a shot. This is some full-on ragtime shit. This is the sound of a house party if I’ve ever heard it. This is like the music they play before movies at old movie theaters. We don’t even hear another instrument before the 50-second mark, and then we have a wistful solo on the clarinet, representative of the Cowgirl protagonist in the ballet. The end of Ranch House Party recalls the theme of the Corral Nocturne as the Cowgirl is once again on her own.

The fourth movement, Saturday Night Waltz, is my favorite of the suite. While I’m often tempted by the playful nature of Buckaroo Holiday or the pure insanity that is the fifth and final movement (we’ll get there), Saturday Night Waltz has always represented, to me, what is so great about Copland’s music. It begins with wide, heavy introduction, fully beckoning you in. Then about 31 seconds in, the main melody kicks in and it’s gorgeous. It’s simultaneously folksy, but colorful and rich and emotive as anything any of the old Germans could have produced. It’s romantic without laying its whole heart out. It’s a ballet romance, after all, so it feels performative — almost too crafted, too sincere, but still. What a good performance it is.

And then: Hoe Down. If you’ve heard anything from Rodeo before now, it’s likely you know Hoe Down. A high-octane joyride of a 5-minute piece that honestly feels as if it’s only 30 seconds long. It bursts open at the start before the strings and horns fade into the background for a little dance between the low strings and the woodblock. The woodblock!! Have you ever heard so prominent a “clack”? It’s magical, I swear to you. When the chorus returns, there’s xylophone added in for good measure. This is an iconic percussion piece with enough parts for everyone to have their fair share. Triangle, snare, crash cymbals, woodblock!!! You name it! There’s also a wonderful solo section midway through, beginning with the trumpet at the 1:43 mark and going into the clarinet soon after then the violin. This Copland also thinks he’s got a false ending in him, bringing it all together at around the 2:30 mark before… it’s very clearly not. Nice try, populism. But our woodblock is back in the spotlight. 🙂 In fact, Copland gives us another false ending after that around the 3:55 mark before… BOOM, it’s our finale. It’s one last recapitulation of the main melody and you’re like, “this is insane now.” Which is fair. Hoe Down is wild and free and strange and funny, which is just about all you can say about American music.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.