Brahms Bangs

This past weekend, I was lucky enough to go see a classical music performance live. You might be thinking, reading this column and knowing I live in Chicago, that I see the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in concert all the dang time and thus that’s an uninteresting way to start this column. You could not, however, be more wrong: it was my first time back at the Symphony Center since 2009! It’s expensive, and I tend to more quickly spend money on things like food and new shirts, especially when I have Spotify. (Spotify… please sponsor me… thank you.)

On the program this past weekend was a performance of Brahms’ Piano Concerto №1 and Shostakovich’s Symphony №5 by the St. Petersburg Symphony Orchestra. I’ve written at length before about this particular Shostakovich symphony, so I’ll spare you most of my fawning. That said, this was the first time I had seen Symphony №5 performed versus performing in it, and woof, it was really something. It’s sweeping and funny and majestic and tragic, and to see it live is really such a rejuvenating and profound experience. I know I already blew my load (sorry) saying that Symphony From The New World is the best symphony of all time (nearly six months and I’m sticking to this bold and potentially incorrect take), but allow me to also add: Shostakovich’s Symphony №5 is the best piece of music in the entire 20th century. Sorry to, uh, The Beatles.

I’ve yet to write, however, about Brahms’ music yet, although I am still reading my giant fucking Brahms book. I promise with my whole heart that this isn’t about to become a piano concerto column, but this particular Brahms piano concerto was one of the pieces I set out to write about before I even got my giant fucking Brahms book. This was a piece that had been stuck in my head for years — among a handful of other Brahms’ pieces — and I felt like I needed to know more about Brahms the person before I could ever begin to wrap my head around what the hell is going on in this concerto.

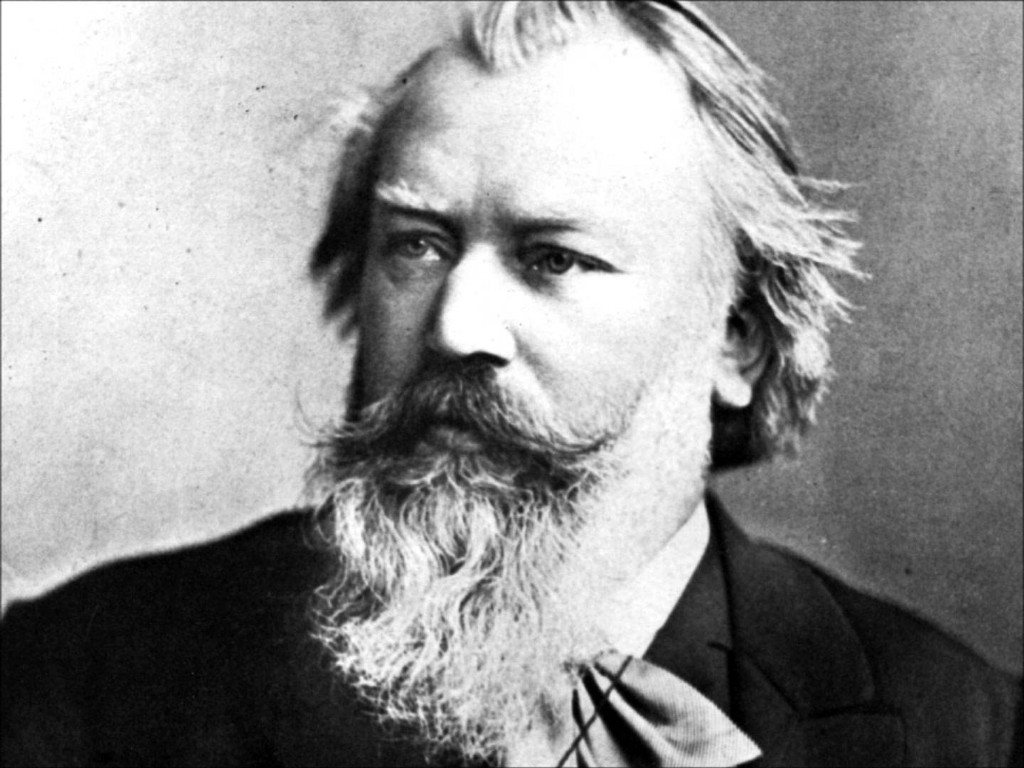

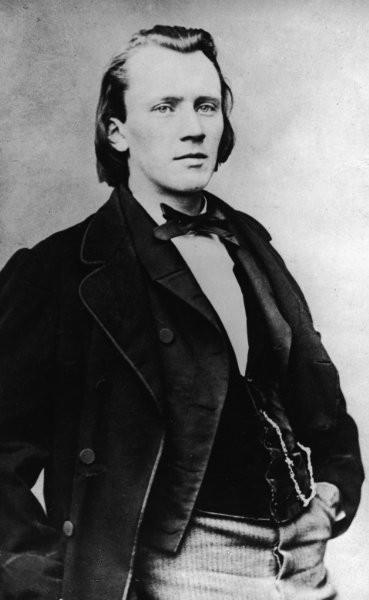

As I mentioned last week, Brahms spent a significant portion of his early 20s staying with the Schumanns in Düsseldorf. There, he wrote and toured and performed around Germany with them in tow as well as his violinist friend, Joseph Joachim. It was during this wayward, romantic period of this time, the 1850s, to be precise, that he composed this first concerto of his. This is really the first major Brahms piece. Brahms loved to destroy his compositions for a while. Much of what existed from his teens — folk songs, little sonatas, what have you — are gone. Today, he would be one of those people who has a plug-in delete all of his tweets after a week. Which is fine! I mean, I don’t care, it’s your account, it’s your legacy as a composer, etc. The deal with Brahms, generally, is that no one really knew what the deal with Brahms was. He wasn’t isolated and obsessive with his craft, nor was he a big social butterfly. He seemed intense and focused, introverted with a lot bubbling beneath the surface in that classic German way, and also, for what it’s worth, pretty hot. Amidst all that, we’re left with a statement of a first big piece.

I actually only want to focus on the first movement of this concerto because there’s enough there to really dig into. Brahms’ Piano Concerto №1 in D minor (New Philharmonic Orchestra from 1998 with Daniel Barenboim as the soloist) starts with a big, deep fanfare — timpani, low brass, you get the drill — before the strings come piling in. It’s not an easy beginning. It’s not an easy piece, period! It’s 23 minutes long! It’s harsh and complicated, almost pushing you away from the music inside of it. Brahms wants you to work for it, which, once again, given what he looked like at the time, sure.

The piano doesn’t even enter until nearly four minutes into the piece, and while its opening refrain is soft and seductive, it quickly escalates once again. It’s a piece of contradictions: equal parts delicate and flowing as well as loud and almost, I don’t know, banging. Not like “this bangs,” but like, “wow, he really is banging on the piano.”

There is a little part in this first movement in particular that I think is one of my favorite piano melodies of all time. Some context within the movement: start at the 13:25 mark and listen to this crescendo between both the piano and the orchestra. It’s disorienting and almost jumbled. Your brain is going to recognize that it’s building to something… significant, of course, but it’s not clear yet. There are two big staccato chords at the 13:41 and 13:42 second marks. And then there it is. This cascading, light melody descending down the keyboard that then jumps back up. And it only really lasts about 20 seconds before the piece moves on melodically. It’s almost comedic. Truly, as I listened to this part live this past weekend, I nearly burst out laughing. It’s so unexpectedly beautiful. The wonderful thing about being able to hear it on a streaming service is you can play that little section over and over again, which, honestly, you really should do. It’s just delightful.

Like I said: that conflict-free section is short-lived because Brahms manages to work his way back up to a restatement of the opening theme, this time on the piano. It’s as if the soloist has overtaken the orchestra, reframing the music on its own terms. Not unlike the Beethoven piano concerto, there’s a real representation of the piano as a deeply powerful instrument in this concerto in particular. The piano is to reckoned with. Maybe it’s a protagonist in the face of adversity. Maybe I’m projecting. Who’s to say? After almost ten years of knowing this piece — and this movement in particular — I don’t feel any closer to it than when I started. The more I learn about Brahms, the more unsettling it becomes. It’s a Rubik’s cube of a piece. And yet, that final minute always gets me. Every time. The pianist: both hands, jumping up and down the keyboard, striking down hard on the downbeats of the melody. It feels chaotic — that humorous part from earlier in the piece coming back, this time in a minor key, like the evil version of itself, all building to a swift, clean climax. In the event that you feel any resolution whatsoever at the end of the movement, don’t get too comfortable. It’s only just begun.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.