Nice Chops If You Can Get It

How one of the last segregation-era businesses in Chattanooga, Tennessee struggles to survive urban development

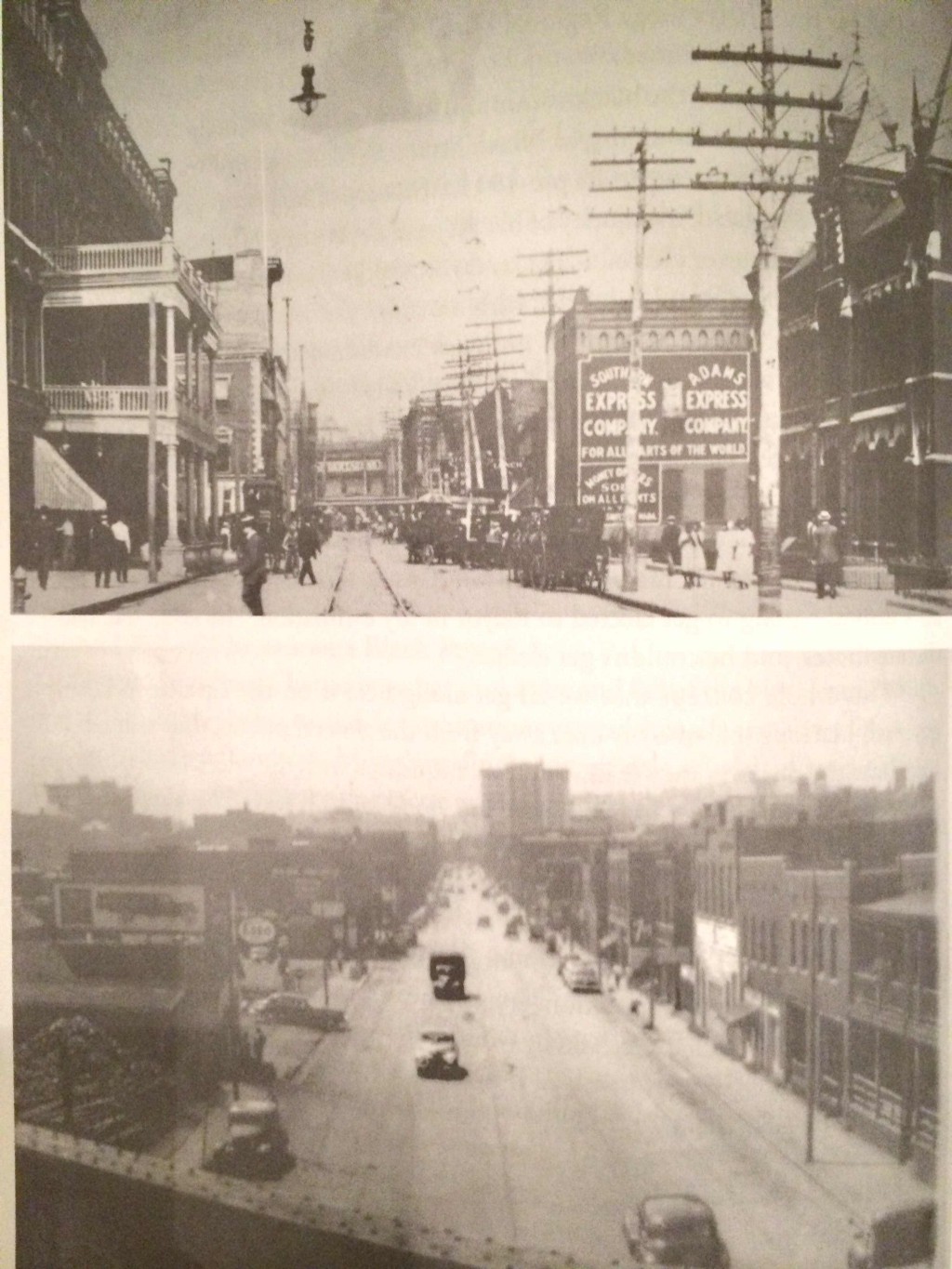

Along the eastern block of Chattanooga’s M. L. King Boulevard, an array of large, colorful murals distracts the eye from a smattering of old, crumbling, graffiti-infested, two-story buildings that desperately cling to a former, much grander life. Before the street’s name was changed in 1982 to honor the slain civil rights leader, it was called Ninth Street, or “The Big Nine,” and it was the epicenter of Chattanooga’s black community.

As a result of segregation, Ninth Street thrived with black-owned movie theaters, grocery stores, night clubs, and countless other businesses for most of the twentieth century. It was also a hotbed for the music scene: Bessie Smith sang on the street corners of the Big Nine as a little a girl; Fred Cash and Sam Gooden played on Ninth Street before forming The Impressions with Curtis Mayfield; same with Jimmy Blanton before Duke Ellington, and Clyde Stubblefield before James Brown. These musicians catapulted the Big Nine to a fame comparable with New Orleans’s Bourbon Street and Memphis’s Beale Street, and even New York’s Harlem; but it was the local musicians who played in clubs and juke joints that elevated the area to its regional fame.

Everyone from Cab Calloway to Jimi Hendrix came to town to play Memorial Auditorium, where until the 1960s blacks were forced to sit in the balconies while the white patrons sat in the better seats on floor level. After their shows, the performers and their bands headed down to Ninth Street to jam with local musicians and house bands who frequented the other venues. After the clubs closed at 3 a.m., everyone would go to down to Memo’s to get their chopped wiener fix. A chopped wiener plate, or “chops” consists of chopped hot dogs covered in a special, secret-recipe chili sauce, served with slaw, a roll and a side of mustard sauce.

Memo’s, a family-owned restaurant open since 1966, is owned and operated by Vic Williams, Jr. and his sister Mona Hammonds, along with their children and grandchildren. Business is steady, with most customers trickling in to get take-out, but it’s far from what it used to be in the heyday of Chattanooga’s music scene. Moses Freeman, a Chattanooga City Councilman, has known the Williams family since 1952 and has been coming to Memo’s for fifty years. Before there was a Memo’s, there was a place called Pit Casaloma’s, Freeman said. When Richard, Vic’s father, bought it, it became a gathering place for those heading out to or coming back from the clubs. “There was a time when Memo’s was hopping, along with the rest of Ninth Street,” he remembered.

Vic Williams, Jr. remembers his father’s first business, an ice-cream store called Frozen Joy. “My dad started working there when he was fourteen. I think by the time he was fifteen, he was manager. So, by the time he finished high school, he got a loan and bought the business.” He then bought another ice-cream shop called Eskimo Joe’s, before finally getting into the chopped wiener business.

Al Hammonds, who married into the Williams family and now works at Memo’s, told me Richard’s wife created the chili sauce for the wieners, and it took off. “She took it to another level. The only thing I can think of is that you can’t get this chili sauce recipe they developed anywhere else.” Hammonds wife and Vic’s sister, Mona, chimed in. “And lots of people try to emulate it, but it’s not the same.” Al was a Memo’s fan well before he married Mona, He was raised on chopped wieners, he said. “Now I can’t get enough. And I work here and still can’t get enough,” he said.

Before it was The Big Nine, it was just Ninth Street. In 1870, John Lovell, the son of a white father and a black mother, set up his business on the street under a tent and sold whiskey and ran a prostitution ring. He eventually earned enough money to build Mahogany Hall, home to Chattanooga’s largest bar and dance club. Another early African-American businessman, E.O. Tade, is regarded as the father of the Ninth Street community, helping to establish a prominent district for blacks to work and socialize in without fear of retribution.

By the turn of the twentieth century, juke joints and bars abounded. Old Crow Place was among the most popular, a place that promoted wrestling matches with a grizzly bear kept in a sawdust pit in the back. But Ninth Street bustled with more than just bars and clubs. Just a few blocks away, Lincoln Park had the first lighted softball field for blacks, and the South’s largest blacks-only swimming pool, thanks to the Works Progress Administration. A teenaged Willie Mays played baseball there as part of the Negro League. Ninth Street was the center of the business district. “It was hustling and bustling,” Councilman Freeman recalled. “We had taxi cabs who ran routes — what we call jitneys — who all brought people here to do business; to buy clothes, to pay rent, to get their hairs fixed, barber shops to get their haircuts, shoe shine parlors.”

“The nightlife was totally something different,” He said. “They operated two and three shifts, day and night because at that time, Chattanooga was a manufacturing town. When one shift got off, they came to Ninth Street. So you have beer vendors open early in the morning to sell breakfast and beer… people would start on one end of the Ninth Street and walk their way to the other end making a lot of bar-hopping, club-popping, and you had a variety of music.”

But starting in the 1950s and continuing for the next two decades, the Westside Renewal Project (or as it was later known, the Golden Gateway Project) dismantled the neighborhood. A product of the Housing Act of 1949, which provided federal funds for cities to buy distressed properties and spawn massive urban renewal projects, it rerouted the new interstate highway routes through Chattanooga. The project forced many of the black-owned businesses of Ninth Street to relocate, and destroyed more than a thousand buildings.

More than sixteen hundred families had to move, forcing the local housing authority to create public housing in other parts of the city. Jeff Pfitzer, program officer for The Benwood Foundation, a non-profit working on revitalization efforts on M. L. King Boulevard, said, ”The wholesale removal of so much — and granted, it was poor-condition housing stock — but the wholesale removal of that much housing stock in an urban environment represented a big displacement of the local population.”

Douglas Turner Day is a folklorist who was commissioned by the Chattanooga’s Allied Arts, the Tennessee Arts Commission, and the National Endowment for the Arts to do a research project to preserve the history of the Big Nine back in the early 1990s. He attributed the loss of businesses and homes of Ninth Street, but the culture as well, to urban renewal, or as he referred to it — borrowing James Baldwin’s line — negro removal. “Those doing the planning and implementation may have had good intentions, but the end result was institutional racism. It may have not been anybody’s intention to try to drive black business people out of doing it but that’s what happened.”

In 1955, the City of Chattanooga authorized changing Ninth Street from a two-way to a one-way road, which meant less traffic running through the area. Williams remembers what this did to Memo’s. “When they made it one way, it almost killed his business because customers were leaving, they weren’t stopping anymore when they were leaving town… And see back then, they just did it. They didn’t have a public forum.” Residents and business owners weren’t included in the city’s decision-making plans.

“The flight of the whites to the suburbs in the past thirty years, followed by the African-American population moving further out killed the downtown,” said Kristy Hunley, Benwood’s program and financial officer. “It happened everywhere, not just M.L.K. The black-owned businesses moved with the population that supported their services. Our downtown department stores moved to the malls.” By the early eighties, the few remaining shops and clubs on Ninth Street had barely enough customers to stay open, but Memo’s survived.

In 1981, many of the city’s black residents wanted to change the name the name of Ninth Street to M. L. King Boulevard, hoping it would spark revitalization efforts in the area. A few white business owners were against the idea, feeling it would be bad for business, but on Jan. 15, 1982, the name change was enacted. In 1986, the Bessie Smith Strut — a free street festival featuring live blues music — began as part of the city’s Riverbend music festival in an effort to drive more traffic to the area. For a while, it worked. Throngs of crowds, black and white, would jam pack on the boulevard, dancing in the street. But in the last few years, crowds have been thinning. The Bessie Smith Hall and Chattanooga African-American Museum opened in the area in 1997 with the promise of other businesses following; they didn’t. The former Big Nine continued to rot.

Between 2002 and 2005, a local organization called M.L.K. Tomorrow incentivized residents and potential home buyers to invest in the neighborhood surrounding M. L. King Boulevard. by helping to fund the construction of new houses and the renovation of old ones. Eventually, a few new businesses sprung up, hoping to take advantage of the expanding student population at the nearby University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, which meant the construction of more dorms creeping closer to the boulevard.

In 2012, local arts organizations began commissioning local artists to paint murals on the buildings on M.L.K. Blvd., acknowledging the area’s vibrant past, something that had been buried for years as the area sank into despair. Among the murals adorned on historic buildings dotted up and down MLK Blvd.. When the AT&T building, formerly the South Central Bell building, was built on Ninth Street in 1973, it looked like a bunker of sorts (To be fair, though, it was built that way in case of catastrophe, so that the city’s phone lines would stay intact). Now, it’s covered in a huge, colorful mural inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Public Art Chattanooga, together with the Benwood and Lyndhurst foundations, commissioned Philadelphia-based muralist Meg Saligman to paint the mural, working with the community to create something that reflected what the Big Nine represents to Chattanooga.

During one of my many visits to Memo’s, Vic told me more about Richard, who died in January, 2016. He told me his father was a strict disciplinarian but he still liked to have fun. He said once, back in the seventies, someone stole several boxes of hot dogs from the restaurant. “The police called and told me that we got your merchandise… that we recovered and we could come down and pick them up. Okay, easy delighted you know? So, when we got down there it was less than what the person said that they had.” His dad didn’t argue and he and Vic took the boxes back to the store. “But the next day we opened, there was a line of police cars lined up, coming in buying hot dogs,” Vic said with a laugh. “I thought that was pretty good.”

A report called “The Unfinished Agenda” was released a couple of years ago by Ken Chilton, a professor at Tennessee State University’s Department of Public Administration. It detailed some alarming statistics about race in Chattanooga. The report says that in the mostly-black neighborhoods of the city, unemployment is staggering, with the average poverty rate at 63.5 percent. It also points out that though urban renewal is a different process now than it was back in the fifties and sixties, the effects are often still the same, with black families being displaced, forced to move to lower income neighborhoods or even public housing, because they often can’t afford the higher property rates.

Back on MLK Blvd., two new breweries have opened up, and another restaurant is in the works. The Camp House, a local coffee shop, moved from it’s location on the Southside to MLK Blvd. to help encourage businesses to move to the district. Student apartments have also been built nearby, a block over from the boulevard. This time, it looks like efforts to revitalize are going to stick. And that’s good economically. But as disappointing as it was to drive through the area when it was neglected, whatever history that was here pertaining to Chattanooga’s African-American community, it looks like is, like everywhere else, slowly being washed away. And as new life is breathed into the Big Nine, Memo’s continues to hang on. But business isn’t what it used to be. In an effort to bring business and music back to the boulevard, Memo’s will begin showcasing live music on the weekends.

As Memo’s celebrates it’s 50th anniversary this month, the Williams family hopes to be a part of the renaissance that seems to be happening all around them. But if the music fails to bring more customers into their restaurant, one of the last of the Big Nine establishments may not be able to survive.

Charles Moss is a writer from Chattanooga, Tennessee. He’s written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post, Slate, and other publications.