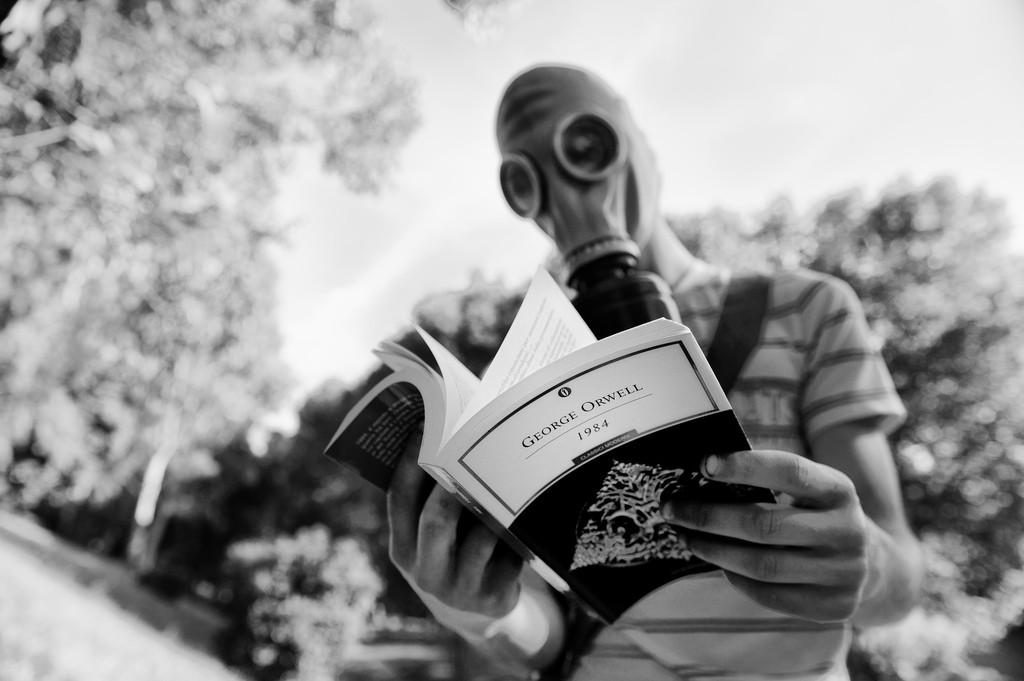

Forget '1984' -- Today, Orwell's Essays Matter More

Forget ‘1984’ — Today, Orwell’s Essays Matter More

You’ll get more from “Why I Write” than from ‘Animal Farm.’

To the surprise of absolutely no one, George Orwell is everywhere these days. His seven-decade-old dystopian classic, 1984, recently made waves by topping a bunch of bestseller lists. Orwell’s earlier (and arguably greater) allegory, Animal Farm, is also getting its due. That both novels are suddenly on the radar of people who probably haven’t given Orwell a second thought in years is hardly surprising at a time when war refugees are painted as national security threats, white nationalists hold positions of power in the White House and an American president is openly involved in an abusive relationship with the English language.

Orwell, the pen name of the Indian-born Eric Arthur Blair, speaks to us in this moment not only because he understood that words have the power both to shackle and to liberate, but also because 1984 inscribed on the literary imagination a vision of what a mass-media-fueled totalitarianism might look like. (He also envisioned what a mass-media-fueled totalitarian victory might look like — a critical aspect of the book’s plot that many people who haven’t read 1984 since high school have probably forgotten. The novel is not a manual of resistance. It is a chronicle of a crushing, obliterating defeat.)

The fact that Orwell was clear-eyed enough, meanwhile, to perceive the brute peril manifest in both Stalinism and in the fascism of a Mussolini or a Hitler provides commentators across the political divide with handy phrases to wield against their ideological foes:

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

Big Brother is watching you.

War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.

If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face — forever.

(Recent events suggest a tasseled loafer stamping on a human face forever might be a more likely scenario.)

Regardless of how prescient Orwell’s novels might seem, his powerful, tightly argued essays remain far more relevant in our current batshit cuckoo political climate. Those readers who pick up his fiction seeking to navigate today’s fraudulent, profoundly cynical rhetoric could well miss out on the best, most concise, most penetrating writings of a man whose constant intent was to interrogate his own beliefs, while holding those in power accountable for theirs. As George Packer, the editor of two excellent editions of Orwell’s essays once put it: “In his best work, Orwell’s arguments are mostly with himself.”

Orwell was an essayist first and last. In his commentaries, columns and criticism — he wrote that the unquiet age in which he lived had forced him to become “a sort of pamphleteer”— he found something original to say about everything from the dehumanizing nature of imperialism (“Shooting an Elephant”) to Leo Tolstoy’s strange, late-in-life attack on Shakespeare (“Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool”) to the beauty and deathless vigor of the natural world (“Some Thoughts on the Common Toad”).

Ultimately, though, many of Orwell’s sharpest, most memorable essays were about the uses and abuses of language. “[O]ne can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality,” he declared. “Good prose is like a windowpane.” With the possible exception of “Write what you know,” that’s as compact a literary credo as one is likely to find. But succinct as it might be, it fails to acknowledge that Orwell’s prose, for all its clarity, was rarely mere glass. At various times, particularly in his essays, language assumes all sorts of roles: scalpel; microscope; mirror; weapon.

Take a passage like this one, from an essay exploring why H.G. Wells (one of Orwell’s boyhood heroes) could never grapple with the true nature of totalitarianism because he “was too sane to understand the modern world”:

Because he belonged to the nineteenth century and to a non-military nation and class … he was, and still is, quite incapable of understanding that nationalism, religious bigotry and feudal loyalty are far more powerful forces than what he himself would describe as sanity. Creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into the present, and if they are ghosts they are at any rate ghosts which need a strong magic to lay them. The people who have shown the best understanding of Fascism are either those who have suffered under it or those who have a Fascist streak in themselves.

That line, “creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into the present,” is still chilling 75 years after it was written — and not only because the modern reader is aware of the scale of the horrors about to be unleashed on Orwell’s world. (The death camps; the Red Army’s rampage of mass rape across a defeated Germany; Hiroshima and Nagasaki; anywhere between 60 and 70 million human beings killed — perhaps more — by the time WWII was over, with civilian men, women and children accounting for at least three-quarters of the dead.)

And yet how many of us have thought, in recent months, that creatures out of the Dark Ages have come marching into our present? Creatures who want women to shut up, stay home, bear children (whether they want them or not) and obey, damn it. Creatures who believe that the diktats of an unhinged leader are not only legitimate, but “will not be questioned” by the hoi polloi.

Consider this passage, from the 1941 essay, “England Your England”:

One cannot see the modern world as it is unless one recognizes the overwhelming strength of patriotism, national loyalty. In certain circumstances it can break down, at certain levels of civilization it does not exist, but as a positive force there is nothing to set beside it. Christianity and international Socialism are as weak as straw in comparison with it. Hitler and Mussolini rose to power in their own countries very largely because they could grasp this fact and their opponents could not.

A love of country — as irrational and unconditional as it might be — is a trait common to people who live in wildly different nations, with wildly different assumptions about everything from how much spice to put in one’s food to how often one should take a nap to how much a country should spend on its military. But it’s precisely because it’s a universal modern impulse that patriotism (or rather its crazy inbred cousin, nationalism) carries such force. In many countries, an intense, xenophobia-fueled patriotism is the only expression of even nominal power available to the poor, the disenfranchised, those left behind. Donald Trump and his advisers grasped this fact; his opponent did not. Or not tightly enough, anyway.

It was in the often-anthologized essay, “Why I Write,” that Orwell came closest to a distillation of his responsibilities as a politically engaged writer:

Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 [i.e., roughly the time when he fought for the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, and got a bullet through the neck for his troubles] has been written, directly or indirectly, AGAINST totalitarianism and FOR democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects.

With that in mind one can read Orwell on Dickens (a man “who fights in the open and is not frightened … a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence”) or the peculiar attitude of the English toward militarism (“English literature, like other literatures, is full of battle-poems, but it is worth noticing that the ones that have won for themselves a kind of popularity [among the English] are always a tale of disaster and retreats”) or virtually any other topic and always come away with a sense of a writer engaged in a long, long struggle to set his own ethics against the savage banalities of his age. (It’s worth noting here that, for all his combativeness, Orwell is far from a puritanical scold. One would be hard pressed, for instance, to read his unsentimental homage to the English pub in the essay “The Moon Under Water,” with its sweet, unanticipated ending, and not respond with something perilously close to “Awww.”)

Orwell never apologized for his politics — specifically, he did not apologize for being a Democratic Socialist in the postwar British vein — but instead bolstered his beliefs by exploring everything, absolutely everything, through a political lens.

So long as I remain alive and well, I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us. —“Why I Write”

Orwell’s essays — more so than his novels — endure as a tonic, and an admonition: Be clear in your arguments. Be curious about the world. Above all, be skeptical of demagogues and of rhetoric grounded not in verifiable facts or demonstrable results, but in hoary appeals to blind nationalism, scapegoating and racial tribalism. “Political language,” he wrote in 1946, “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Right now is as good a time as any — and better than most — to turn from Orwell’s novels to his essays, where language itself is held to account and the only wind the reader encounters is the bracing gale of a fearless mind at work.