Rather Be The Detective

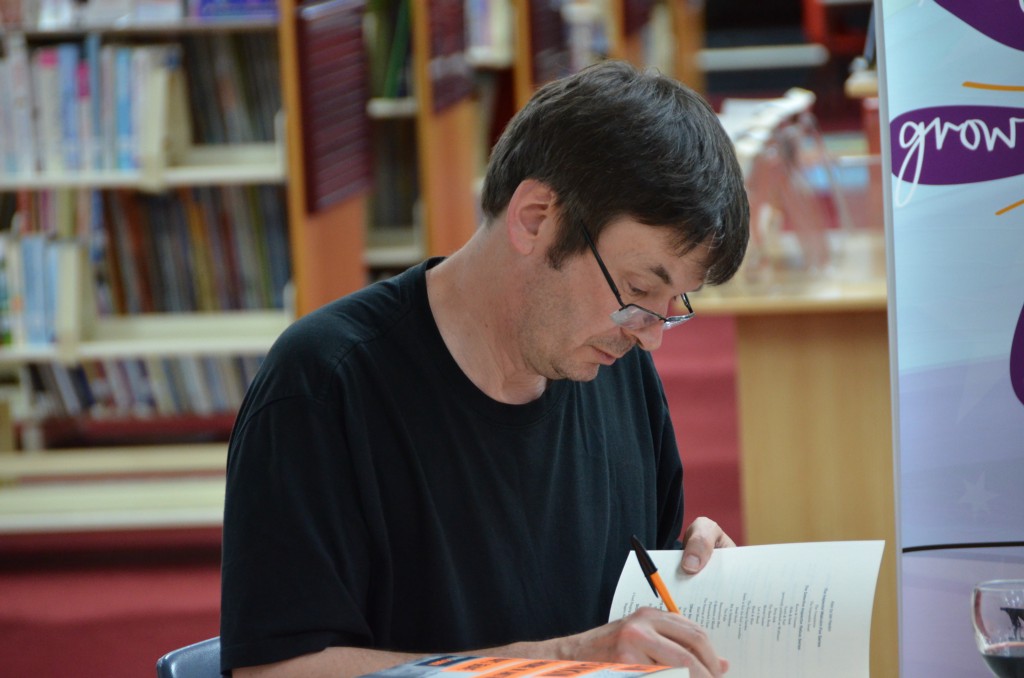

The Scottish crime novelist Ian Rankin and his alter ego, a hard-boiled investigator.

The “Oxford” Bar — inverted commas their own — is synonymous with crime writer Ian Rankin, though his fans are warned by papers and travel guides that they are unlikely to run into the author himself there. The place is a draw for pilgrims familiar with Rankin and John Rebus, his hard-boiled detective of the present day who drinks there when not uncovering the crimes of a hidden Edinburgh. But on a mild and grey January afternoon, the author was in residence. The woman behind the bar, who asked me for ID, which I didn’t have as I was just ordering a coke, relaxed about my presence when he came in.

“It’s a traditional old-fashioned pub, which is why my detective drinks here. No TV, no jukebox, doesn’t do food, just a place for alcohol and conversation,” said Rankin as we sat down in the back room. He arrived one minute after me at exactly three o’clock, and bought my coke as well as his own. He had a hangover: Friend’s birthday last night, a late one — but he seemed O.K.

Rankin was writing a Ph.D. thesis on Edinburgh author Muriel Spark when he started visiting the “Oxford” bar, and became an author himself, taking an interest in the stories from the cops who drank there in the evenings. “I mean, The Great Edinburgh Novel was Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark, which was set in the 1930s,” he said. “And until Trainspotting came along, there was never much written about Edinburgh since then. There was a lot of writing happening in Glasgow in the ’80s when I started. There seemed to be lots of contemporary novels for Glasgow, but nobody doing the same for Edinburgh.”

Films, and novels where people visit the city from London often reference the grand fanfare of streets with regal names, or romanticize the small wynds and closes (BrE for narrow lanes and alleys, respectively) of the old town. Rankin’s novels go into the unbeautiful estates which Edinburgh natives know, and visitors to the town seldom see. He writes about poverty about injustice, and the marginalisation of crimes committed against asylum seekers (Scotland’s Asylum seekers still face appalling abuse.)

Like Rebus, Rankin is a champion of the vulnerable members of society; the victims whose voices are not heard. He is angry at the treatment of people in Dungavel, an immigration Removal Center fifty miles out of the city, and wrote about the centre — thinly veiled — in Fleshmarket Close.

“The reason I wrote about it was that I discovered that a lot of children were being kept there, and they weren’t getting a proper education. There’d be one teacher for all of the kids, so you know if you were ten-year-sold, five, sixteen, you’d all be in the same classroom at the same time with the same teacher. I just thought it was a terrible thing to do to any kind of immigrants, illegal or otherwise, locking them up in a place like that and then not giving them a proper education.”

However, beyond this innate decency and a fascination in human nature, the two have little in common. At fifty-six, Rankin is ten-years younger than his detective, but they have a similar sense of disgust with injustice, similar taste in music (popular rock songs segue into one another in the books to represent a change in mood — in Devil Over The Hill by John Martyn plays, triggering Rebus’ realisation that he isn’t there quite yet), and a similar taste in bars. But Rebus is older.

“I think it’s a long time before I become a grandparent,” he said. Rankin is married with two sons, while Rebus’s obsession with his work led to the breakdown of his marriage, though he does have one daughter. “He is a generation older than me, so I’ve always got to make sure that it’s him not me that’s thinking you know? How would a guy in his mid sixties think? And I don’t smoke, so I think would he be reaching for a cigarette right now? Probably. Would he be having a drink? Probably. What music would he be listening to?”

At times, Rebus has been his punching bag. “Anything that’s going wrong in my life I can just channel it to him. So, when my younger son was born disabled, I put Rebus’s daughter in a wheelchair for a couple of books, and that was just a way of dealing with it, so he’s saved me a fortune in psychoanalyst bills really and any big questions I have about the world, I just dump them on Rebus.”

Readers of Rebus novels look to the stories for comfort. While there is no formula, there is an element of ease in the knowledge that ambiguous good will trounce evil, however much is lost along the way. And that which is lost adds an element of bittersweetness to the novels. Would Rankin’s readers not feel betrayed if he were to stop writing about Rebus?

“Yeah. But it’s happened before. Agatha Christie stopped writing about Poirot, Colin Dexter stopped writing his novels about Inspector Morse… I can’t keep writing the books because I can’t keep finding things for him to do.” I told him I liked the idea of Rebus solving crimes in an old folks’ home. “Maybe that could be the final book then,” he laughed, “well actually, there is someone, I think it’s Michael Dibdin [in his novel End Game], who wrote something about people in an old people’s home investigating mysterious deaths of people in the old people’s home, and you were never sure if they were being bumped off or were just dying of natural causes.” So, you could have a Harold Shipman character, I suggested, referring to the U.K. doctor who was also the country’s most prolific serial killer. Rankin laughed. “That would be very jolly,” he said.

Rankin was recently named a Fellow of The Royal Society of Literature. “it’s kind of recognition, I suppose, that crime fiction is literature,” he said. “I think some people, when they think crime fiction they immediately think the Agatha Christie style of story, which is a puzzle, and it’s a puzzle you have to solve, and that’s the main pleasure, is actually solving the puzzle, but these days, contemporary crime fiction isn’t so much about the puzzle, it’s more critiques of society.”

He said he gets a lot of the ideas for his books from newspapers, and writes to make sense of them: “I sometimes have to write a story, just to kind of give it some closure.” He has also gleaned stories from locals cops. “I mean there was a gangster through in Glasgow whose nickname was The Licensee, the reason they called him the Licensee being that the police had given him a license to continue to operate as a gangster, because he was giving them so much information that was useful to them.” He also pronounced Big Ger (Morris Gerald Cafferty, a gangster and Rebus’s nemesis) as Big Jer instead of Bigger. I’ve been pronouncing it wrong all along.

“It’s all right” Rankin said, “a lot of people call him ‘Bigger,’ and nobody knows how to pronounce Rebus either. Is it REBB-us, RAY-bus, REE-bus? I say it Ree-bus, but but the only ever time I met a guy who’s name was Rebus he pronounced it REBB-us. And it’s a Polish surname. It’s also a picture puzzle, and the reason Rebus is called that is because in the first book he’s getting sent picture puzzles, so it’s sort of, a little in-joke”

“And then, a year or two ago I was in a bar in Edinburgh and guy introduced himself to me, and his name was Joe Rebus, and he said ‘oh, I thought you got the name out of the phonebook,’ you know — the phone directory, and I said ‘No, it’s a picture puzzle’ and he said ‘it’s also a Polish surname’ and so we got the telephone directory from the barman to look him up, and there he is Rebus, J for Joe and, his address is Rankin Drive. How weird is that?”

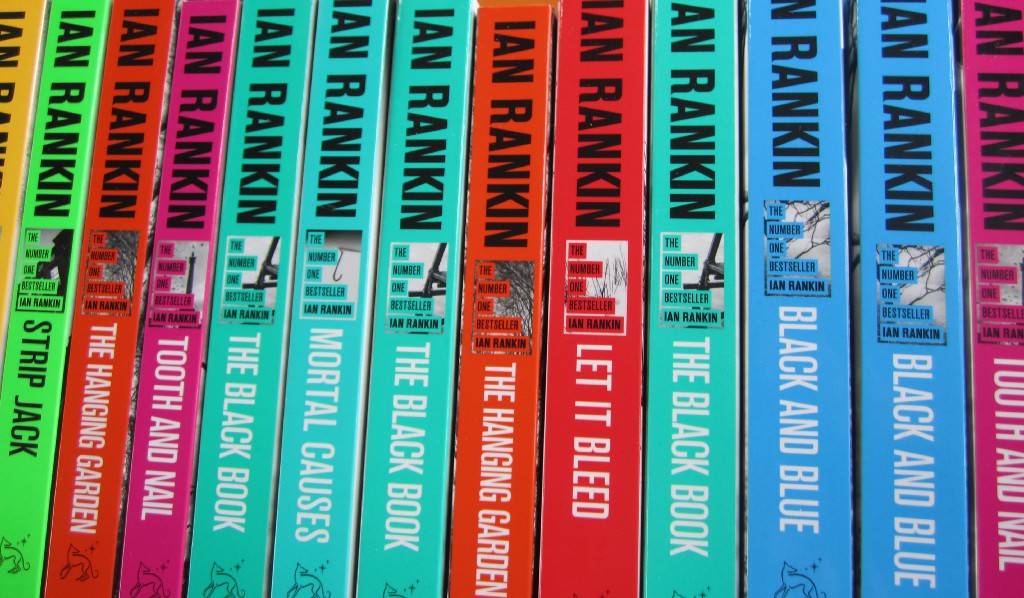

Rankin’s novels are often described as Tartan Noir. In several of the public libraries where I’ve worked in Edinburgh, Scottish crime is categorised separately from crime writing, it’s supposed difference marked by a square of red tartan stuck to the spine of books. What, I asked Rankin, is Tartan Noir? And how are these books different from say Scandinavian noir, English noir and American noir?

“Well, it’s, it’s a lazy shorthand way of talking about Scottish crime fiction. But in fact the word noir would suggest that Scottish crime fiction is very dark, you know? Very Scandinavian. But in fact it isn’t necessarily. It’s a very broad church, the Scottish crime-writing community, so you’ve got someone Alexander McCall Smith writing about Mma Ramotswe and those aren’t noir, they’re still crime fiction but they’re not noir.

“You’ve got books set in Shetland, you’ve got books that are set in rural communities, remote communities, you’ve got books that are set in big urban cities, you’ve got books that have satire and comedy in them. You’ve got books that are very gritty and hard hitting, you know? So there’s a Scottish crime writer out there somewhere writing the kind of book you want to read. So if you want it light and frothy I can give you a Scottish Crime writer to read, if you want it dark and gritty I can give you a Scottish Crime writer to read.”

Rankin coined the term himself, while getting James Ellroy to sign a book for him in about 1995. “I said to him,’ I’m a crime writer as well. I write what you could call Tartan Noir’ and so he wrote in the book ‘To Ian Rankin, you are real Tartan Noir’ or something, so then I pretended that he’d invented it.” It was just the kind of thing I could imagine myself doing — attributing a clever quote to someone else to give it a credibility I feel it wouldn’t have coming from me.

After our interview, Rankin went to speak with some fans. Then we both walked down the narrow cobbled road, as far as Princes Street. He told me the The “Oxford” bar used to have a ‘boat race’ with its neighboring bar, The Cambridge Bar — people would run to and fro drinking pints between the pubs. At the end of Princes Street, he turned East to go into Waterstones — a UK chain of bookstores where he bought Philip K Dick’s dystopian novel, The Man in the High Castle. I turned west, towards the Union Canal, back home through the city of John Rebus, a city which is very different to a cynical but decent fictional cop, and a girl who writes and works in libraries. As I passed Haymarket, a police car sped past, sirens screaming.