High Spirits

The Nevada City Shochu Diaries

In November, I went to Japan on a sponsored trip designed to introduce beverage writers and other beverage professionals to a Japanese spirit called shochu. Shochu is delicious and interesting and mostly distilled from barley or sweet potatoes, though sometimes from other things. It has roughly half the alcohol content of things like vodka or whiskey, so does not really have the fiery burning instant buzz situation of those liquor traditions. That said, a British businessman I met at the Shinjuku Station Starbucks who decided to become sober immediately after such an experience assured me you can get epically wasted out of vending machine shochu cocktails.

Drinking shochu is a good way to drink spirits AND taste your food. After my trip, I went to the Brooklyn restaurant Karasu with my friend Frank, who works there, and we had steak. Because I am a completely garbage person, I was drinking whiskey — I was in the mood for it — but then Frank suggested I have some shochu with my steak. The steak was already out of this world, but it instantly became 10,000 times better, and you can trust me, because I am not an annoying “pairings” jerk.

Also, shochu is not to be confused with soju — the stuff people without liquor licenses put in your Bloody Mary. Also, this has all been a long aside. The story starts now.

The shochu trip itself was going to be six days, and on Japan’s southern island, Kyushu. But it seemed if I was going to go all the way to Japan, I should spend some time seeing more of the country. So I arranged to spend three days in Tokyo on either end of the Kyushu trip. On the front end of my trip, I decided to take a side trip to eat at a newish restaurant called Izakaya High Spirits, in a town near Mount Fuji called Fujikawaguchiko. The owner, Tsuyoshi Natori, is a friend of a Facebook friend. I know that doesn’t seem like a terribly tight connection, but Natori also lived in Nevada City (where I live) for several years, and worked as a chef at a really good Japanese restaurant here called Sushi in the Raw.

Since the shochu portion of my trip was going to be guided and fairly regimented (which was absolutely fine with me—traveling in Japan is challenging for a non-Japanese speaker) this Mount Fuji mini-jaunt was to be my one adventure. I had seen Facebook posts that suggested eating and drinking at Izakaya High Spirits was sort of like hanging out with a bunch of good friends that you just met while also eating good food and drinking good booze. I was a little worried about the sociability of it, because maybe I was too old for that sort of thing, but I figured I would give it a try.

After two days in Tokyo with a college friend (an endlessly entertaining and generous host who took me for steak at the Park Hyatt and sushi at the Ritz-Carlton) I boarded a train, in Tokyo Station, winningly called “The Romance Car.” As the beige Tokyo suburbs gave way to a more wooded, mist-filled landscape, I bought a cup of green tea from the woman walking up the aisle serving snacks and drinks and felt rather pleased with myself.

A hour and a half later, we pulled into a station. A light, almost frozen rain was falling. I had that helpless childlike feeling of having no idea what to do next, which always feels so weird next to the adult, adventurous feeling of traveling alone in a faraway country. I recall the train station as having a ski lodge-like feeling, but I could be totally wrong about this; I took horrible notes in Japan because I was always just trying to figure out what was going on. Anyway, there was a glassed-in information booth and I handed the woman inside it a piece of paper with the address of my hotel written on it.

“This is Hakone,” she said. She did not smile.

I told her I understood that, but wasn’t Fujikawaguchiko just a short taxi ride away?

It was not. It was about three hours away, and not three hours away on another beautiful train. It was three hours and three buses away.

I began arguing with her.

This did not make her any less correct nor draw any closer the town of Fujikawaguchiko.

How had this happened? Well, imagine if you were in New York City on vacation and you didn’t know shit about it or the surrounding area. Imagine also that not only did you not speak any English, you spoke a language comprising totally unfamiliar symbols altogether so that everything in your range of hearing and line of vision was both confusing and fatiguing. Then imagine you had a plan to make a side trip, the details of which you hadn’t yet attended to, because you weren’t the sort of person who always attends to things.

Then let’s say, finally trying to attend to things, you told one New York City resident, “I’m going to Upstate New York! (Which you thought of as ONE PLACE) How should I get there?” And, for some reason, this person said with total certainty, “Oh, you’re going to take Metro North to Cold Spring!” Then imagine the exact same conversation took place with a totally different New York City resident a few hours later, and you thought you had the right information, because why would two people tell you the same thing if it weren’t true?

And then imagine that you took Metro North to Cold Spring, when in fact you were supposed to take the Greyhound to Kerhonkson which is neither spiritually nor geographically anywhere near Cold Spring.

In short: two separate people who did not know each other, on two distinct occasions, upon hearing me say I was going to Mount Fuji, exclaimed, “Oh, you want to take the Romance Car to Hakone!” And it didn’t occur to me that they might both be wrong.

Outside, there was a long queue for a bus to take me deeper and deeper into Japan. The rain intensified. I had not eaten anything all day. The green tea had, as it often does, briefly staved off my hunger, but then pitched me into depths of a desire for nourishment so mercenary and unchecked that I found myself staring at a nice Brazilian couple’s bag of cookies. “Here,” the woman said, handing some over, because who says “Would you care for any?” to a wolf?

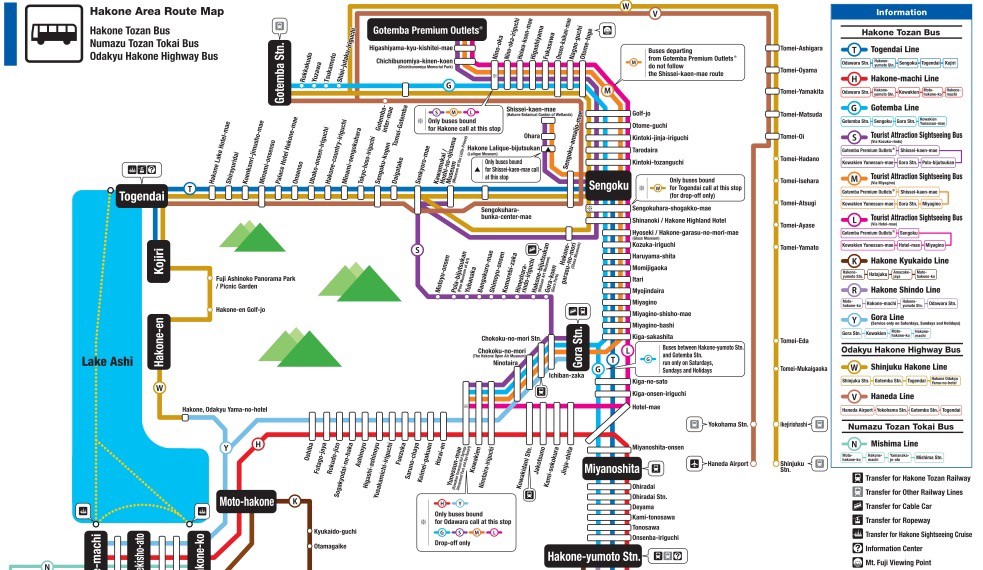

Also, I had no cell phone. I didn’t trust AT&T not to just fuck me with a three billion-dollar bill (“No, your international plan doesn’t actually work THERE!”) so I had signed up for NO PLAN and was going through Japan like it was 1980, no map function, no Google. The information booth lady had given me a map, which showed the first two buses and the first two destinations. The third bus route, and the third destination, did not exist on any map she had in her possession. No, after some place called Gotemba Station (not to be confused with Gotemba Premium Outlets?) it seemed I would be heading off into nothingness.

From Hakone, which was old and “authentic” but touristy, we climbed a narrow winding mountain road. There was a lot of thick foliage and mist. It was beautiful, but it was hard to relax because I was not at all confident of my next move. Everyone on the bus except for the Brazilian Cookie Samaritans was elderly and Japanese. A red digital sign at the front of the bus let you know which stops were coming up, but a lot of them sounded very similar. There were four stops in a row that began with “Miya.” And I was getting off at some place called Sengoku, but there were two other stops — Sengokushara and Sengokushara-bunka-something. A constant stream of automated Japanese coming out of the bus’s loudspeaker successfully prohibited any kind of thought.

I was overwhelmed.

I stood up as we approached what I was pretty sure was plain old Sengoku. “No, no,” chorused the Brazilians, “This isn’t your stop, it’s the next one!” I felt bad defying them because they’d given me a cookie, but I also felt strongly that they were wrong. I got off.

A sign read Sengoku but I did not find this terribly reassuring. I wasn’t exactly in the middle of nowhere; I was in a small town clutching a mountainside, and there were buildings and stuff—proof of civilization. But there was no one around. I thought wistfully of the shitty but attractive black Naf Naf raincoat I bought in Paris, from a salesgirl who said proudly as I tried it on, “This is the biggest one in the whole store.” It was hanging in my friend’s closet in Oakland. I’d actually taken it out of my bag and left it there at the last minute, to save space, and because someone (not either of the people who’d told me to go to Hakone, no, some other wrong person entirely) had told me it didn’t rain in Japan at this time of year. By now it was pouring, great buckets of famously sweet Japanese water falling unremittingly from the Japanese sky.

I stood on a corner under my $11 umbrella, glad it wasn’t a $5 umbrella. I laughed out loud. What else could I do? After about five minutes, a teenage girl emerged from the mist. She was wearing headphones and a surgical mask. Surgical masks are very popular in Japan. They are supposed to be all about protecting yourself and other people from disease, but they’re also worn to indicate a lack of sociability, with which I theoretically sympathize but at this particular moment found inconvenient. No fool, the girl started to cross the street before she reached me, and I shouted “Excuse me, excuse me” and then even ran after her. She did not break stride. She did not even move her eyes.

If you have utterly humiliated yourself but no one is around to witness your humiliation, is it possible it has indeed not taken place? Asking for a friend.

I picked a direction and walked. I was lucky enough to come upon a tiny fish market, where a woman of about sixty and a man about half her age who I imagined to be her son—because who besides someone’s son would agree to spend his life with a woman twice his age running a fish market in a nearly empty town clinging to the side of the mountain—were hard at work. No actual words were exchanged, but somehow, the “son,” in a white, blood-splattered apron, walked me back to a spot slightly up the block from whence I had come, a small parking lot outside what was possibly a municipal building and where no person would have ever guessed, not in ten thousand years, buses picked people up and dropped them off. As we approached, he waved to a girl standing on the sidewalk near the parking lot, and called something out, and she called something back, and beckoned. As I joined her she bowed and smiled, and, when I held out my sodden map and pointed to my destination, she nodded and said “Hai.” I smiled at her, willing myself not to burst into tears of gratitude.

We stood there silently as the sky unburdened itself of a mere fraction of the 1,668 millimeters of water that fall yearly on this beautiful island nation.

The bus arrived within ten minutes. I indicated to the bus driver that I needed to sit down to get my wallet out of my bag but he indicated no such shenanigans would be taking place.

(May I voice an aside about Japan? You can’t just be like “Oh, gee, what if I engage in this tiny deviation from the way things are usually done because everything will all turn out O.K. in the end anyway?” In my extremely limited experience, I would say that the Japanese do not give a fucking shit about how things turn out in the end. What I’m trying to say here is, when you get on a bus in Japan, have exact change in your hand ready to go.)

After fishing in my bag and stumbling around and clutching at railings for God knows how long, I collapsed, sweating, into a seat. I listened to a Barbara Vine audiobook and napped. We climbed and climbed and climbed and the rain kept coming, harder and faster. I began to feel like I was in a cozy, sweet, adventure story rather than a dark, dangerous one. The Japanese girl smiled at me encouragingly, as if to say, “You’re doing a really good job sitting on a bus.”

These feelings of security disappeared when I arrived at second to last stop, a parking lot with no discernible place to get another bus. My encouraging young buddy was gone. I wanted to get off the bus quickly and figure out my next bus, because it was quite possible it was the last one of the night. But when I tried to disembark, a man was standing at the bus exit. He was talking to the driver, who glowered at me. His eyes said, “I remember you, hapless female American change fumbler!” I bowed a little and smiled. The man blocking me made eye contact but didn’t move. This went on for a while, until I walked down the bus stairs, thinking, “Surely he will get out of my way” at which point he did not. I literally shoved past past him, muttering, in English, naturally, “Get the fuck out of my way, you fucking asshole.”

(There are those who would call me an obnoxious American. I say, if you’re traveling alone as a woman, there are moments where men are going to try to teach you a lesson. It’s up to you to let them know that indeed, no lesson has been learned.)

Nearby, there was a little cottage-type thing that looked like a place where you might buy bus tickets. And it was. But not for my bus! No, my bus and bus ticket awaited in a brutalist era horror show on the other side of the parking lot. Once there, I trotted up some sad concrete stairs to one ticket window only to discover that my ticket window was down the stairs and out the door and on the other side of the building.

My ticket was really expensive. I didn’t mind paying—I really wanted to go to this restaurant — but I was worried by how the expense suggested I was not as close to my destination as I might have wished.

This town looked like any not nice, unremarkable city near open space. There were lots of puddles and young men splashing though them on mopeds. There was a drugstore, and some ugly bars. It reminded me of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, or Lancaster, California, or Ibagué, Colombia, but I was only standing in one corner of it, so what do I know.

This bus itself was not a touring bus but a municipal bus, and I shared its chilly utilitarian emptiness with five teenagers — four girls and one boy, all in school uniforms. They sat in a row. One boy snuggled with one of the girls, and they were sharing one black knit hat like a cigarette. All five of them dozed intermittently and I waited until a moment when they were all awake to ask if any of them spoke English. The made self-deprecating faces and muttered “a little.” Then they all pointed to the boy, who leaned forward and said, “I am the best.”

He was handsome and had acne. “Am I actually headed toward,” I read it syllable by syllable — “Fu-ji-ka-wa-gu-chi-ko?” They all laughed.

“Do you guys take this bus back and forth to school every day?” I asked. We had been climbing the steep side of a mountain for at least an hour. He said yes. I said, “Holy shit.”

“Why you on this bus?” he asked, and I said, “Because I am an idiot.” Everyone thought this was very funny. I was happy to be of service. (To be fair, I am not the first American to get on this particular bus. It was full of advice for backpackers, in English. Still, it is a very stupid way to get from Tokyo to Fujikawaguchiko.)

I was very relieved when we pulled into a small but proper bus station. In keeping with its reassuring theme as a universally recognizable place where buses pick people up and drop them off, several taxis were waiting. Sadly, none of their drivers had the slightest idea of where my restaurant or hotel was, and none of them spoke English. This presented a challenge. There was nothing I could do other than show them the address over and over again and hope for the best. I suppose I could have just crawled into the bushes and died, but instead, I just sat in the back of a taxi and waited until the guy asked literally every single person at the bus station where to go. Finally, someone knew. The guy hated me, but he could get in line.

Ten minutes and ten dollars later (a total of six hours and $140 dollars later) I arrived at Izakaya High Spirits.

I opened the door to a room about the size of a suburban bedroom. The lighting was like a doctor’s office. There was room for maybe twenty people, literally. An Italian couple sat on the floor at a low bar, and behind it was Tsuyoshi, or Go, as people call him. He was in his thirties and tall and it was not easy to make him laugh but when he did laugh he laughed heartily.

I am Sarah, I said. After what I had just gone though, I kind of expected a fucking marching band to come out of the kitchen. I had managed to turn my phone on for a minute and tell him I was indeed coming, but he hadn’t gotten the message.

He just nodded. “I didn’t think you were coming,” he said.

“I’m here,” I said again.

“Yeah, I know,” he said. I wanted him to be more excited that I was there, but I saw that I could not force this. There were liquor bottles gleaming on the bar and raw fish glistening behind the glass. I wanted it all.

I saw that they didn’t take cards. So out into the rain I went again. Go told me the bank machine was about seven minutes away, which might have been true if I were a gazelle. There were two possible choices and I of course picked the one that did not take my card first. But I finally emerged with $200 in cash and ran back to the restaurant.

The first thing I had was a barley shochu, Bakuretu, from Yamanashi prefecture. Go gave it to me on the rocks. He advised me against starting off with a sweet potato (imo) one, which is probably a reasonable way of proceeding, since those have flavors many Americans have not tasted or tasted a lot, and which, two months later, I still don’t quite get. But anyway, this barley (mugi) shochu was fragrant and slightly floral smelling, and had a liquor’s warm satisfying richness but was smooth, and didn’t overpower the plate of sashimi I had. I have no idea what sort of sashimi I had, because I was just starving and ate it like it was oatmeal, but it was fresh and delicious and served with a soy ginger sauce.

A young guy who worked in finance in New York showed up and sat next to me and we drank more of the barley shochu and both ordered some sliced beef with salt on it. I love beef. This was perfect beef—rare, high-quality, marbled, cold. There is nothing to me like plain good beef with salt and a drink that goes with it. “Meat is the bomb,” said the finance guy, and I said it sucked that we weren’t supposed to eat it anymore. “What are you talking about?” he said, and I said, “How do you not know that?” and he said “I don’t know, I just don’t.” He was a well-educated, successful person who was naïve as a ten-year old. I kept laughing at him and he both liked and did not like this.

Then I ordered a sweet potato with miso butter, a really simple thing that is very delicious.

Meanwhile, the Italian couple started explaining to us the ways in which Italy sucked and then I started explaining to them the ways in which America sucked, and they said I did not have to explain this because they had already lived there. Then the young guy said he thought of Europe as this wonderful place where everything was chill, and the Italians laughed very hard, and I laughed along with them, and Go laughed too. “Wow, you’re mean,” the young guy said, not really bothered, and then we ordered sweet potato shochu, also on the rocks, and agreed it tasted unusual but that we wanted to keep drinking it, to figure out why. We didn’t. It definitely doesn’t taste like sweet potato-flavored alcohol though.

Around 9:30 p.m., deep into the Italians explaining to us what a Berlusconi presidency had been like, twelve guys from Thailand showed up. Go told them he didn’t have a lot of food left, but that he had drinks and snacks. They got bottles of sake and encouraged us to share. They tried our shochu. The finance guy asked me what I was doing in Japan, and I said I was there to drink shochu. “For a whole week?” he said. “More or less,” I said. He looked mystified. “Is that like, a job?” he said. I explained to him that I had an adventurous life that was also hard, but he didn’t believe the second part. I told him I lived in a trailer behind a jail. “Shut the fuck up,” he said. It’s true, I said. It’s a really nice trailer and a really nice jail, but would you want to live in a trailer? He didn’t answer. I ordered squid. I love squid, the way it gives under your teeth, and this stuff was good, smelling just faintly of sea air and not much else. “What are you guys doing here?” I asked the Thai guys, because they seemed like they must be on some kind of sports team, but no, they were all just here on vacation. “Same as you!” Go said, and everyone laughed at me and everyone drank more. Everything was just as Facebook promised.

It was just a short walk back to the hotel. It was rainy but warm. The town was modest and, after the city, fairly empty. I was only about ninety minutes from Tokyo, but because I traveled so extensively I felt like I was at the end of the earth. I dragged my suitcase over puddles and brushed my hand over wet Japanese weeds. I wonder where Mt. Fuji is, I thought to myself, before I went to sleep, too bad I won’t get to see it. In the morning, I walked out of the hotel and it was right there, looming over me, white, as big as the sun.