Dvořák's 'Slavonic Dances' Are Like A Musical Mood Ring

Classical Music Hour with Fran

When I started this column a couple of months ago, I introduced you to Antonín Dvořák, a Czech romantic composer who I argued wrote the best symphony of all time. I stand by that claim, if only because I’ll be @’d to death if I ever back down from it, but I wanted to return to Dvořák this week to introduce you to a different piece. The Dvořák from Symphony From The New World is older, more experienced, “has been to New York City and by extension, Brooklyn, and maybe by further extension, the Williamsburg Whole Foods.”

Antonín Dvořák’s ‘Symphony From The New World’ Is The Best, Bar None

The Dvořák from this week is not that guy. He hasn’t even left the Czech Republic yet (or Czechoslovakia, lest we forget that 150 years ago, Europe was very different). Between 1878 and 1886, Dvořák wrote 16 Slavonic dances, known as, uh, the Slavonic Dances. They came in two sets of eight: Opus 46 and Opus 72. Personally, I’m mostly familiar with Opus 46, the first eight Slavonic Dances, which I’d like to introduce you to. These were my initial introduction to Dvořák, who again, is a much different figure than the one we met trying to capture the spirit of “American classical music.” This Dvořák was trying to capture the spirit of Czech music — or do anything, really, to get his name on the map.

In the mid-1870s, Dvořák met Brahms through an Austrian composition contest (“Why haven’t you written about Brahms yet?” you’re asking me, and the answer is because I have a 600-page biography of him on my nightstand that I haven’t gotten around to yet), and Brahms introduced Dvořák to his publisher. His publisher commissioned the dances from Dvořák who, again, was something of an unknown. And unknown was kind of Dvořák’s plan when he sat down to write these Slavonic Dances. So he modeled them, of course, of Brahms’s Hungarian Dances. You think you don’t know any of Brahms’s Hungarian Dances, which is hilarious, because you definitely do.

And so: we get these eight Slavonic Dances, significantly more upbeat and fun and strange and full of zest. Are the Czech people a more upbeat people than the Hungarians? I am literally not at liberty to say.

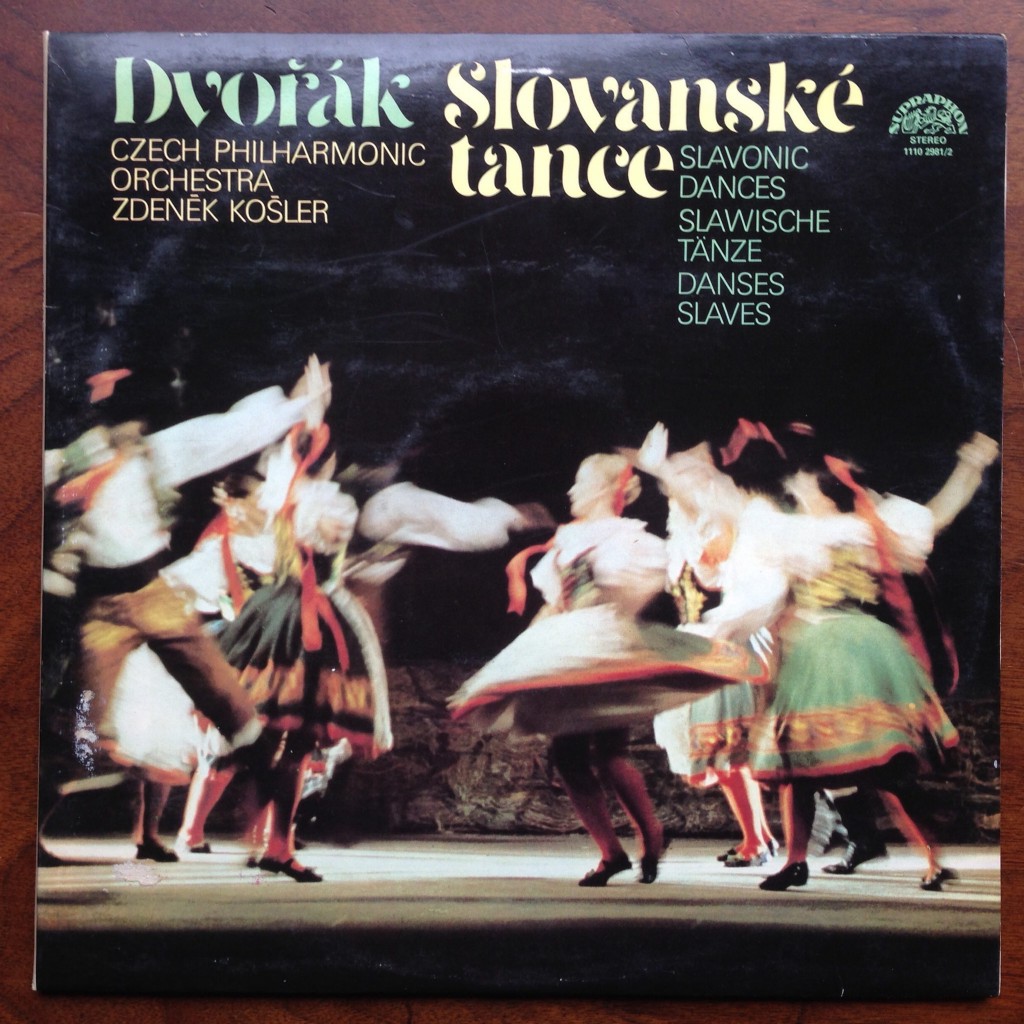

I am going off of a rare 2016 recording of these dances this week, done by the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra themselves. Feels just like the right way to do this, you know?

The Slavonic Dances are something of a mood ring, if that makes sense to you. Depending on who you are and where you are and what you’re feeling, I genuinely think one or two of these is going to speak more to you than others. Which is fine! Not all of the Slavonic Dances are “for me,” but I’ll do my best to walk you through the mood and tone of them.

Right out the gate, you’ve got #1: the Presto. This one is, uh, not usually for me. It starts with a fanfare — triumphant and boisterous. The strings are perhaps a little too high and forceful off the bat for me, but maybe you’re the kind of person who can’t enter a room quietly. This is a set of dances after all, and you need something (or someone) to really kick things off. I start to warm up to it a little at the 1:22 mark; there’s this cute little melody in the woodwinds that plays over the cellos playing about as high as they can. It’s very elegant at its heart.

With #2, the Allegretto scherzando (“quick and playful”) starts with a very coy woodwind melody. This one is seductive: not quite a slow dance but not too upbeat (especially as some of these get more wild). It feels a little more broad and sweeping in its core melody, and then goes into this quicker drum and cymbal part. That’s where the playful comes in, I imagine.

Now then, the #3, Poco allegro, is extremely my shit. This is one of my two favorite movements in the whole set. I could hum this melody for days on end. It starts smooth and in control. Again: we get these really gorgeous high long notes holding on the cellos. The sound is so rich and wonderful. Cellos are just maybe the best instrument in any orchestra. And then, at right at the 0:47 mark, what the heck! It speeds up. It catches you off-guard with a little chorus before falling right back into its core melody. The middle section of the piece also boasts this wonderful little horn feature. I don’t even care about horns but suddenly it’s like, all I care about are horns. Dvořák, you dog!!!

I played these for a coworker sometime last week when I was reacquainting myself with the Slavonic Dances, and she mentioned to me that #4, the Minuet, sounded like someone entering a ball for the first time. This one feels very royal, no doubt, like presenting oneself to society. It runs a little longer than some of the other dances — just over seven minutes, rather than four or five. This one is rich, too, with a couple of different themes through. It just never really pulls that bait and switch of suddenly getting all upbeat and cymbal-heavy like some of the others. That’s okay. This one gives you a break.

Molto vivace, the fifth dance, is nuts!! It’s quick! It’s cymbals! It’s snare! It’s loud and fast and short and keeps itself going and going! It’s one of the least memorable ones in the set to me, not because it’s bad, but because it almost moves along too quickly for me to get ahold of the melody. Who knows: maybe you operate at this speed. Maybe you let yourself have more coffee than me. I don’t know you or your life.

Now then, #6 is yet another Allegretto scherzando like the second dance. When I think back to my experience of playing Dvořák and specifically the Slavonic Dances, this is the one I remember most even though I do not think it is extremely my shit. I remember being told to constantly play this one more delicately. Which: fair, I suppose. It does feel lightweight, like if you held it in your hands, you’d be afraid to drop it on the ground. It’s perhaps ultimately too precious to me — the little string melody at 1:13 is like the music equivalent of getting your cheeks pinched by an old aunt.

We get back into my type of thing around the seventh dance, the Allegro assai. I love this oboe solo up top: it sets such an interesting and curious mood. Oboe is a naturally curious instrument to me, always just like, “Hm? Me? I’m here?” rather than other instruments that are just like, “I’M HERE.” But regardless, my favorite thing happens right at the 0:34 mark. Once again, we get this quick little woodwind melody over cellos playing on the high end of their register. I GO NUTS FOR THIS AND I WISH I WERE KIDDING. The Allegro assai is also a great example of what a good “variation on theme” can look and feel like. This piece is really just the same two melodies over and over again, back and forth, but they’re layered differently and somehow, Dvořák (MY GUY) keeps layering them in new and interesting ways that build tension.

Last but not least, we get #8 which, just like the first one, is a Presto. There’s a particularly finite feel to this one. It’s almost angry! Dvořák… no… it’s just dancing… don’t get angry. The back and forth between a lighter and more jaunty melody and the really heavy stuff is almost like Dvořák convincing the listener that his particular sound is here to stay. It’s not just fun, he’s explaining, it’s also meant to be taken seriously. (Dvořák, we get it.) I’m not sure the eighth dance is anyone’s favorite, but again: if you can find something, good for you.

I’m not telling you to pick and choose between the Slavonic Dances. No, no, hell no. I’m saying, set aside about forty minutes to listen all the way through. Some of them are going to blend into your emails and your g-chats and your reports (I don’t know what any of you do for a living), but some of the others will pop out. It’ll let you escape what you’re doing for just a bit (again, these aren’t very long) and yes, you have to tell me which one it is that gets you to do that.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.