The Lady Chablis, After Midnight

At the memorial service for Savannah’s breakout transgender star

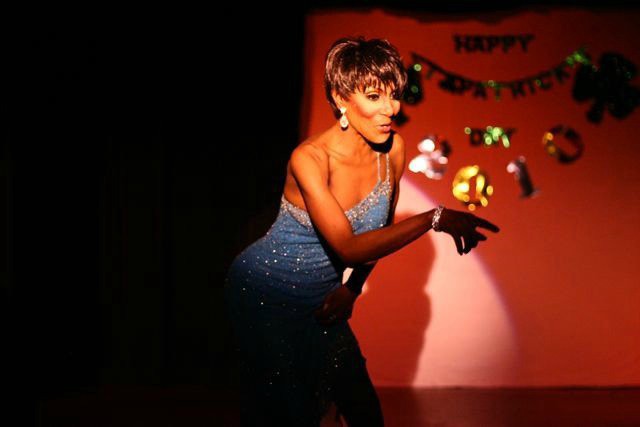

Befitting the Grand Empress of Savannah, the Lady Chablis memorial service lasted from before dusk until well past midnight. Family and friends and fans filed into the historic Lucas Theatre in downtown Savannah on November 5th to honor the transgender performer and breakout star of the book and movie, The Midnight in the Garden of the Good and Evil. She died of pneumonia in September, at the age of fifty-nine. In the lobby, a red urn containing her ashes was flanked by four of her sequined gowns. Inside the theatre, photos and videos of her looped on the widescreen, and more than a dozen speakers told stories of a diva, a generous friend, an electric entertainer. Afterwards, Club One, the gay nightspot that was her artistic home, hosted two tribute cabarets. “From the grave, she is making me put on this last big show,” said her longtime friend Cale Hall, a co-owner of the club. “That’s fitting for her.”

Before there was “Transparent” or Laverne Cox or “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” there was the Lady Chablis. She was a black transgender performer for decades before it was accepted as it is now, which is still not nearly enough. Famed drag queen Lady Bunny, who had flown in from New York, recalled the first time she saw Chablis. It was at a gay club in Chattanooga in 1977. “I had never done drag before,” she said, her signature big blonde hair coiffed in a black mourning veil. But when she saw Chablis and another entertainer, she said, “I knew that whatever they were, that’s what I wanted to be.”

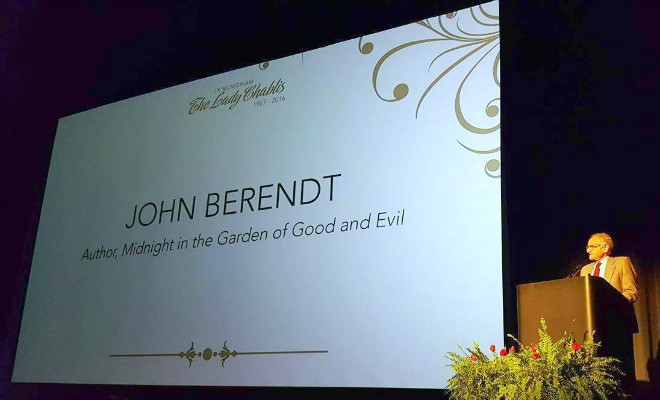

“Chablis was at the forefront,” John Berendt, author of Midnight, told the attendees. He recounted the day thirty years prior when he met Chablis in Savannah, after she invited herself into his car for a ride home. He wrote her into his runaway bestseller, which made her a star well beyond the club circuit. “She was one of the first transgender performers to win acceptance by a general audience,” he said. Afterwards, everyone had a Chablis story. People devoured the book, or they watched her steal scenes from John Cusack, or they saw her on “Oprah.” Tourists and suburbanites and bachelorette parties poured into tiny clubs to see her.

I knew Chablis because she was my childhood neighbor. My father was her landlord for nearly twenty years. He and Chablis lived in a row of aging, one-story brick houses on a block in West Columbia, South Carolina. My dad moved there after my parents’ divorce, back into the house he grew up in, where I would spend weekends and summers. Our family had long rented out the house on the corner as an income property. Throughout the 1980s, the lease had been passed down through word of mouth among a circle of lesbian couples (whom the neighbors called “roommates”) and who were mostly artists and performers at a local comedy club. Through them, the rental eventually found its way to Chablis, who lived there longer than anyone else.

My father looked like an unlikely ally: a ruddy-faced welder and pipefitter who rarely dressed in anything but blue coveralls, whereas Chablis, even in casual clothing, exuded elegance. My first clear memory of her — I was likely ten or eleven — came when I tagged along as my father fixed the plumbing under her sink. Racks of clothes filled the kitchen, stuffed with ball gowns and cat suits, full of sparkle, leopard, and faux fur. She was likely getting ready for a show, and packing up what she needed. This was right around the time the book came out, and though we knew she was a performer, we had no idea she was becoming famous. We wouldn’t know until sometime later, when Dad caught a glimpse of her on the “Today” show.

Chablis had a wicked sense of humor. She took great joy in her ability to rib my father, and most anyone, with bawdy jokes. In recent years her constant companion was a fluffy white dog — a maltipoo — who was hyper and ill-behaved and adorable. She named him Cracker. It tickled her to no end to let him run loose in her yard, and call out after him — “Cracker! Cracker!” — repeating at a loud decibel for her mostly white, grey-haired neighbors to hear. “She could defuse racial or trans tensions just by being herself, just with her humor,” Lady Bunny said at the memorial.

Her monthly cabaret shows at Club One, where she had been performing since 1988, were full of camp and glamour and wigs. But at home, I most often saw her in no make-up, with pixie-cut hair, and her corset-sized figure draped in a t-shirt. There, she was simply Brenda Dale Knox, as her friends would say, and not the stage presence of the Doll, the Empress, the Lady Chablis. When she found out I wanted to be a writer, she said I should write a book about her and call it, A Black Boy in the South Who Likes to Wear Dresses. I told her that title might be a little long. She ended up writing her own memoir, suggestively called, Hiding My Candy. But for all her gender-bending talk, she lived as a woman — a point too often missed during her media heyday.

Chablis hated labels. She defied gender essentialism, even as many reporters tried to make it an issue, labeling her derisively, and sometimes for comic effect, in headlines and copy as a “he/she.” Now it seems almost standard for the media to talk about gender non-conformity, but back then the public’s insistence on boundaries only made Chablis more apt to break them. She came to loathe the label of drag queen. “The word ‘drag’ offends me,” she once said in a newspaper interview, adding, “I live as a female.” She ultimately preferred one label, and that was her legal name: The Lady Chablis.

Movie stardom did not protect Chablis from a certain kind of peril. Then as now, renewed attention to the trans community brought with it greater awareness and understanding, but also the threat of the wrong kind of attention. “I couldn’t go to Big Lots or anywhere,” she once told a Savannah reporter. “That person behind me might be a fan but it could also be some redneck following me. Not everyone is into the Lady Chablis.” After years of living in Georgia, she moved to South Carolina, and commuted back for gigs, partly because her new city offered the anonymity that Savannah did not. “I picked West Columbia because it’s the last place anybody would expect to find me,” she quipped to our local newspaper after the book hit the bestseller list. She often talked about the movie outing her: After, strangers knew her as a “transvestite,” not as a woman they passed on the street. It made her a target.

Her health deteriorated. There are few paid sick days for club performers, and there is a notorious lack of steady work for trans people. Money came and went. For years, she paid her rent in wads of cash from her tips, until my dad drove her to the bank to open a checking account.

It would be wrong to overstate my relationship with Chablis. At its root, she and my father had a business relationship, which I inherited. She was my neighbor, and I knew her when I was a child. And when I was no longer a child, I still reverted to a shy state of awe around her. Like many others, I was lucky to have known even glimpses of her. My father died in 2012; there were medical bills and debts to pay, and his home was in foreclosure. I had to sell the little house on the corner. Chablis didn’t want to leave, and I didn’t want her to go. For a long time, my father had wanted her to buy the place, but she couldn’t, and so by the end of the following year, she moved out. When I drive past now, there are tricycles and a trampoline outside. Someday, I think I will stop and knock and tell them about the people who used to live on their block, in their houses. I will tell them about The Lady Chablis.

I took for granted that there would be more time, and that I could always find her at one of her shows. I imagined a road trip to Savannah, a reunion after midnight, at the club. There would be time to tell her again how sorry I was she couldn’t stay in the corner house, how I regret how it all ended. That is, in part, how I found myself in the basement of Club One on a Saturday at the reception, where guests ordered drinks and served themselves jambalaya from the bar. Nearby sat Chablis’s sister Cynthia Ponder, the spitting image of her. At the memorial, Ponder said she believed God had a plan for her sister, that she was to give to the world something, even through the struggles. I asked her what it was like growing up in Quincy, a rural community in the Florida panhandle. “We were from a very small southern town,” she said, “but you can’t hold someone like her back from being their true self. I’ll put it like that.”

Chablis was stubbornly, exuberantly herself. There’s a magnetism about that kind of confidence, about seeing someone with such an unabashed sense of self, no matter who is watching. And watch they did. The movie and the book are still everywhere in Savannah, in hotel brochures and on the tongues of tour guides. Tourism skyrocketed for the city, and locals have John Berendt to thank. But they also owe gratitude to the cast of gay and transgender characters at the book’s center, a point that conveniently does not make its way into many official tourism talking points.

“She put Savannah on the map,” Destiny Myklz (pronounced “Michaels”) told the crowd at the Lady Chablis tribute show. Myklz emceed the Club One cabaret, which included lip synch performances from the club’s regular line-up, many of whom worked for years alongside Chablis. There was a country number to a Sugarland song, and a dance number to a Beyoncé medley. There were mile-high wigs and contour make-up. There were sequins and gowns and teensy underwear and knee-high boots. The show, as Chablis might have said of her own, “was not a Disney production.” At the end of the set, Myklz thanked the audience for helping them honor the Lady. She lifted her arm in the air and pointed her hand to the sky, saying, “This one’s for you, Doll.”

Tiffany Stanley is a writer in Washington, D.C.