The Arc Of The Atlatl

The rise of spear-throwing among hobbyists and modern hunters

In the autumn of 2007, Aaron Swope of East Hempfield, Pennsylvania, killed his first deer at the age of seven. His grandfather, 61-year-old Russell Guthrie, who’d brought the boy out to hunt near Buck, Pennsylvania, that day, caught the kill on video and posted it to a local outdoorsman forum. Almost immediately, the video was drowned in a hail of gushing-to-critical comments from the state’s hunting community. Some were impressed that a boy that young had not just made a kill, but had done it after sneaking up on the deer and striking it from just 15 feet away. Some were judgmental about the fact that the kill happened on a private preserve, where the deer tend to be more docile, less skittish — not a fair hunt. But the vast majority were captivated by what the boy had used to bring down the deer: a six-foot-long dart launched from a shorter strip of wood he held in one hand, a prehistoric hunting tool (not so) commonly known as an atlatl.

Not long ago, few people could identify an atlatl, much less known how to pronounce it. (It’s aht-lah-tuhl, not atl-atl.) Actually even today few in the general populace can. Yet in recent years, a small but growing group of enthusiasts have worked to revive interest in and knowledge of this simple, ancient weapon. In America, it’s caught on especially with certain subgroups of hunters, who proselytize the joys and value of working with atlatls. Some of acolytes of the elegant yet rudimentary device see it as a novel challenge — a fun new test of their physical skills. But for many, especially in the hunting community, the atlatl is a symbol of romantic primitivism through which they can write themselves into thrilling, virile narratives of the hazy, heroic past.

For the uninitiated: atlatls are basically pre-historic ball launchers; their underlying mechanics are similar to those involved in the Basque sport of pelota, or jai alai as it’s known to many in the Americas. A length of wood, bone, or ivory is carved into a board, about two feet long, with a handle at the front and spur at the back, upon which a long dart with a pointed tip sits. A thrower draws the atlatl back in one hand, holding the dart in place with a hooked finger, then hurls the apparatus forward, loosing the dart. There’s some variation depending on the design and the darts used, but many launch their projectiles at up to 100 miles per hour, with accuracy of up to 40 yards, achieving about 200 percent more penetrating power than a dart thrown by hand.

“It takes very little to make either the atlatl or the [dart], and both are immediately usable,” said Elizabeth Horton, a University of Arkansas archaeologist. She’s hosted events for people to try their hand at flinging atlatls, among other prehistoric human skills. “It’s an extremely difficult skill, but one that you can do with a wide range of people and age groups.”

This simplicity and power likely accounts for the wide usage of atlatls throughout many of the world’s ancient societies. Although some believe humans have been using atlatls for 30,000 years, the first evidence of them shows up in European cave paintings from 15,000 B.C.E. Evidence of them has been found everywhere in the world, save (to date) in sub-Saharan Africa. In America, they’re best known through accounts of the Spanish confrontation with the Aztecs, from whom we get the term “atlatl” and who, used the devices, which probably traveled with humans as they first moved to the continent, well into the 16th century C.E. But other groups, from Australia (where some aboriginal peoples called them “woomera”) to the Yukon (where the Yup’ik peoples called them “nuqaq”), likewise used atlatls to hunt and fight into the modern era.

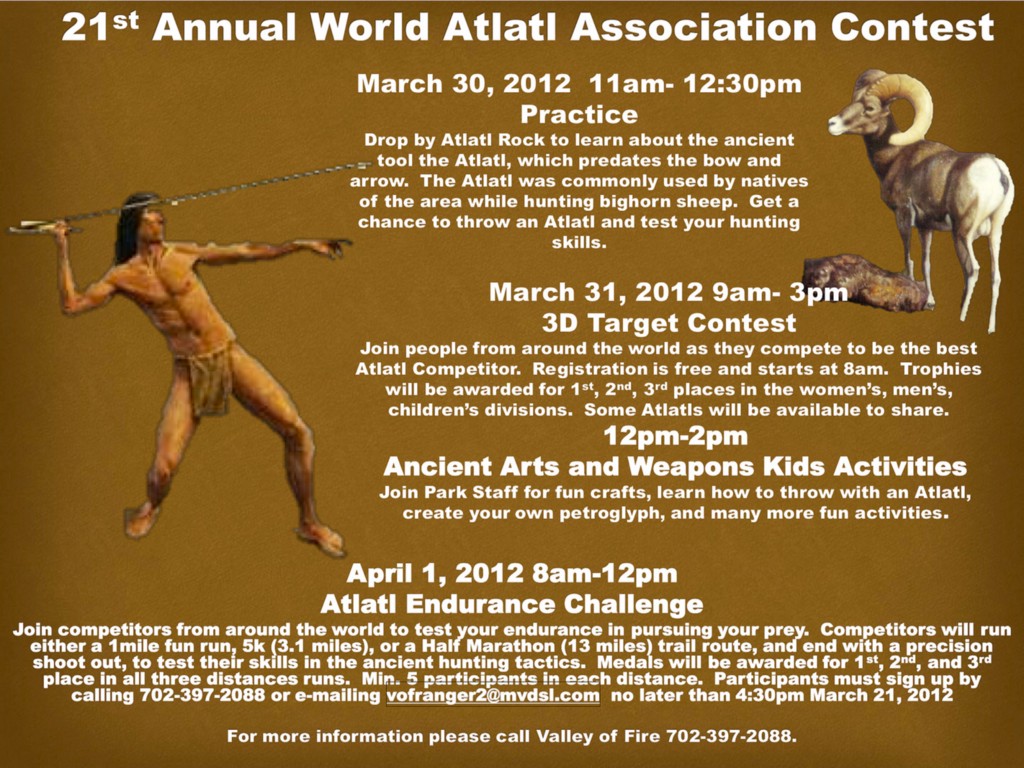

Experimental archaeologists have long played around with reconstructed atlatls, to understand their research subjects and to unwind alike, but at some point their enthusiasm spread to a critical mass of students. In 1987, a group of wonks formed the World Atlatl Association (W.A.A.), which brought enthusiasts together for accuracy competitions, like the International Standard Accuracy Contest. There was enough interest by then that some folks, like William “Atlatl Bob” Perkins, who’d built his first device for a term paper while at Montana State University in the 1970s, were able to launch companies — Perkins’s BPS Engineering out of Manhattan, Montana, is one of the bigger and better known outlets — selling dart throwers of all sort for collection and sport.

“I [throw atlatl darts] to have fun and see my atlatl friends when I make it to events,” said Courtney Birkett, executive director of the WAA and a working archaeologist, of the draw of the devices for her and many academic types. “I’ve sometimes thought it’s like anything else that has a devoted following — like science fiction or other things that have conventions.”

In those early days, only a handful of people were interested in reviving the actual use of atlatls for hunting. Bob Berg of Thunderbird Atlatl in Candor, New York, near the Finger Lakes — another big name in the atlatl world and an advocate of atlatl hunting — said when he got into the community in the late 1980s, there were perhaps half a dozen atlatl hunters in the nation.

Once Berg and his cohort started spreading the gospel of the atlatl in the hunting community, though, it took off in a major way. There are nowhere near as many atlatl hunters as there are bow hunters even (in no small part because it’s hard to find places in which it’s legal to hunt with an atlatl). But while about a quarter century ago you could perhaps count the number of atlatl hunters on your hands, today Berg suspects that of the thousands of atlatls he sells each year, about ten percent go to hunters. The community of atlatl hunters has grown so quickly and enthusiastically that they’ve even formed the Atlatl Hunting and Fishing Association, backed by Berg, to lobby for the legalization of atlatls as hunting tools in regulated zones across America.

Atlatl hunters aren’t a huge lobby, but there’s enough vim and vigor in it that they’ve succeeded in pushing atlatl-hunting legislation in Alabama, Missouri, and Nebraska in recent years, meaning that you can hunt for regulated game with a prehistoric dart thrower in four states now. At least one bill to legalize atlatl hunting has floated around in Montana. (Atlatl hunting was apparently always legal in Alaska, and many others have long allowed the use of any weapon to hunt unregulated animals, or allowed the use of atlatls to spearfish.) They managed to get it provisionally cleared in Pennsylvania a decade ago, but within months the implementation of a hunting season was shelved indefinitely due to concerns about the lethality of the device, especially in the hands of amateurs, and their potential to cause undue animal suffering. (Private preserves, like the one Swope killed his deer in, are free from these restrictions in Pennsylvania and some other states.)

For some hunters, like 50-year-old Paul Gragg, who made Missouri state news last fall when he took down a massive whitetail deer with a seven-foot dart with a twin-bladed broadhead tip in the wild, five years after the state legalized atlatl hunting, the devices are just a new challenge — something to get excited about after years of bow-hunting, for which he holds local records.

“A guy told me no one had ever killed a deer in Missouri with an atlatl, so I though it might be interesting to try,” Gragg told local reporters. (This wasn’t actually true. The first deer was brought down with a modern atlatl in Missouri in 2011.) “I’m not real educated on the history of atlatls — it’s just another opportunity the conservation department offers for hunting.”

But for many others, the atlatl’s appeal is all about connecting them to what they sometimes describe as the “roots of humanity.” Some atlatlists have argued atlatls were the technology that transformed us from scavengers into hunters — and implicitly turned us from passive animals into potent men, stewards of the earth. Others talk about it as a means of traveling back into the past, away from a technologically dominated now.

Many events featuring atlatl trials advertise the dart flingers as a measured, hands-on means of gaining an intimate and physical understanding of and respect for archaic life. Firing an atlatl “is one of the quickest ways to get out students to think about past life in a more personal way,” said Horton. “It immediately dispels any lingering notions of past peoples being ‘primitive.’ Anyone can ‘do it,’ but it takes a lot of skill and knowledge to do it right and well.”

Hunters like Berg attempt to be methodical and academic in their approach to exploring the past through atlatls. He recalled that he recently brought a young man on an atlatl hunt with stone tools with which to butcher a freshly slaughtered deer as part of research for a Masters thesis. For Berg, these pursuits about holding fast to traditional knowledge, or dredging it up from the depths of time as best as possible, to keep a piece of the human narrative from slipping away.

However, some veer into talking about atlatls as a means of better understanding local indigenous cultures in a way that feels worryingly like an unintentional exercise in “playing Indians” in the guise of deep anthropology. A local story on a new atlatl event put on by Arizona City’s Pueblo Grande Museum in the spring of 2014 featured descriptions of organizers hitting cardboard sabre-tooth tigers with atlatl darts and claims about the inherent, marrow-deep human affinity for atlatl-throwing alongside notes on appreciation for local indigenous culture. Another event, this summer’s “18th Annual Bald Eagle Knap-In, Native American Primitive Arts Show & Atlatl Tournament” at Pennsylvania’s Bald Eagle State Park, advertised itself with the following phrase, laid out immediately beneath a banner of clip art stone arrowheads flanking crossed clip art spears: “This exciting two day festival will transport you back to a time of primitive life.”

Atlatls and atlatl hunting show up on survivalist forums and primitivist portals, which promote disengagement from modernity in favor of a simpler, cleaner, and more meaningful past of raw human skill and ingenuity. It’s an old impulse — the same one that’s long led scout troop masters to teach their wards how to do things the old way. It’s am embrace born of despair with the modern world and a deep belief that prehistoric technologies are either essential for a coming apocalypse, or that they are morally superior in their simple elegance.

On the edges of this impulse, or at its core, is an Edenic, Rousseauian view of primitive man and the primitive world. It’s an image of early hunters not as complex peoples in perpetual and dynamic technological and social development, but as stoic and skilled moral agents, possessing an autonomy and power we wish to possess for ourselves again. It’s an image of the past that strokes and stokes what it means to be masculine, to be a provider, to be a capable individual.

Atlatls are amazing. They are incredibly efficient for simple bits of organic matter, drastically increasing man’s natural might through a little skill and knowledge. Their proliferation across human cultures speaks to a common ingenuity and development, one of those rare universal human narratives. They can serve as portals into a rich and diverse past. But especially as they bump up against and spread into communities with their own philosophical readings of the past, they can also transport us into myth. We ought to be keenly aware of where these ancient devices take us, and what baggage we bring into our encounters with them as well.

Mark Hay is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn.