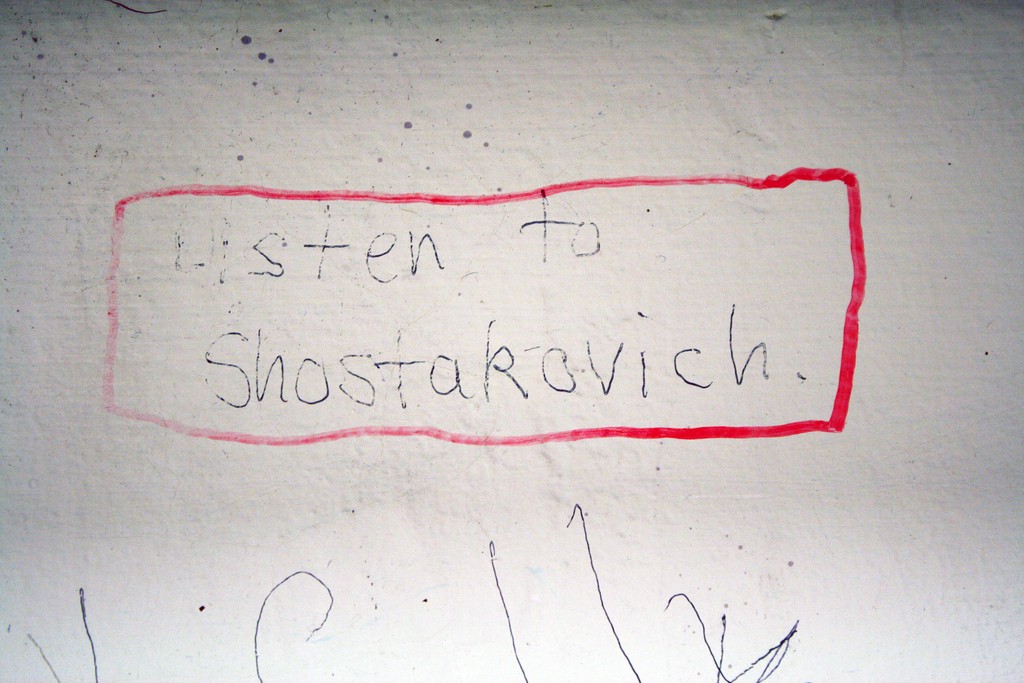

Protect Shostakovich's 'Festive Overture' At All Costs

Classical Music Hour with Fran

Dmitri Shostakovich is very much my boy. The way that some Tumblr girls feel about Marvel characters or CW characters, who caption their .gif sets with “protect so-and-so at all costs”? That’s me and Shostakovich. He’s just my nervous little guy. I feel so bad for him. All he wanted to do was compose his music all the while being upstaged, essentially, by Joseph Stalin and the rise of Communism. Did anyone else write a paper on a historical figure when they were approximately nineteen years old and now feel a fierce maternal affection for them? Please chime in.

Shostakovich’s history is immense and troubled and very necessary to understand, I believe, to get a full grasp on any of his pieces. I first played Festive Overture when I was in high school and thought it was a blast. It’s like a rip-roaring, 6-minute little adventure. It was tough in high school to be a timpanist if only because a lot of being a timpanist (or a concert percussionist, generally speaking) involves sitting and counting rests until you play once every, say, 4–15 minutes. I don’t care how good your attention span is as a fifteen-year-old, that shit is impossible. So you have Festive Overture, which is not only relatively short, but has a full, bouncing percussion section complete with an essential snare drum feature at the 2:34 mark. The whole thing just moves. By the time you hit the final fanfare at the 4:50 mark, it’s kind of like, “Oh man, it’s almost over? It just started.”

For this week’s recording, I’ve chosen the London Symphony Orchestra in 2011. You should start listening to it now and then read the rest of this. Okay? Okay.

Shostakovich is perhaps one of the least approachable composers I’ve wanted to write about so far, in part because his work is something of a chameleon. Festive Overture is the easiest entry point, I’d imagine, for someone who’s not familiar with the Russian composer’s work. Shostakovich is also the most modern of the composers I’ve written about so far, born in 1906 and having died in 1975. This puts him right smack in the middle of Every Important Thing To Happen In The 20th Century Minus Disco.

The reason I feel so tenderly for Shostakovich is that to be an artist of any kind during the reign of Stalin was to live in a constant state of terror. I mean, basically anyone living under Stalin lived under a constant state of terror, but you get where I’m going. For the first near decade of his life, 1927, when he graduated, to 1936, Shostakovich was able to compose at will. In 1936, however, Stalin attended Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth opera, which was later panned in Pravda, the official newspaper of the Communist party for being “coarse, primitive and vulgar.” Ay yi yi. From there, Shostakovich withdrew from society for nearly a year, focusing on his family and taking a break from writing. In the meantime, he saw the execution or disappearance of many of those close to him, including his patron Marshal Tukhachevsky, his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks, his friend Nikolai Zhilyayev (a musicologist), his mother-in-law, his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova, and his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky.

Shostakovich eventually returned to the scene in 1937 — taking a full year off as a professional composer was a fairly big deal, this wasn’t like now when you can just cash in on miles and go to Bali for a year and everyone is like, “this is fine.” In 1937, he launched something of a rebranded self with his Fifth Symphony (we’ll get there eventually, I promise) who was Very Into Communism And Stalin And The State, which, obviously, of course, he wasn’t, but it needed to be done in order to secure both his and his family’s survival. From there, Shostakovich became something of a crown jewel of the Soviet Union during the Second World War, his music seemingly nationalistic to the powers that be.

So let’s go back to Festive Overture, the fun little jaunt that my high school self loved to play. Festive Overture was composed in 1954 at a concert at the Bolshoi Theatre to commemorate the 37th anniversary of the October Revolution. Why is 37 a significant number of commemorate? Uh??? I don’t know. What is wild, however, is that Shostakovich wrote Festive Overture in three days. Knowing that and listening to it, it does feel a little, “Ah, shit, I gotta get this done.”

There’s that level of it, the general sort of rushed “I need to get my overture turned in on time or everyone will be mad” aspect to the tone of it, and then here’s this: the 37th anniversary of the October Revolution was, in fact, very significant because it was a year after Stalin’s death. And while this overture is in no way connected to that — that piece, in fact, would be Shostakovich’s 10th symphony, which, you know, I’ll get to eventually — it does have this nervous, almost relieved energy to it? If you know to look for it, that is. This is also the first and only piece that Shostakovich conducted himself. I can’t help but picture him, this poor anxious guy, terrorized by the state for twenty years, stepping up on stage to conduct this piece. It’s very cute? I mean, obviously it’s not cute at all, but there’s something darkly funny about it.

So now start the piece over. It’s short, you can listen to it twice, it’ll be fine. You don’t have that much to do for 12 minutes of your life. It’s still triumphant and fun, no doubt, but now you’ll be able to sense the tension, the uneasiness of it. It feels like someone who might be on the run from a lot of different things, all the while forced to shout back “No, no, I’m not running from you at all!!!” Like I said, protect Shostakovich at all costs.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.