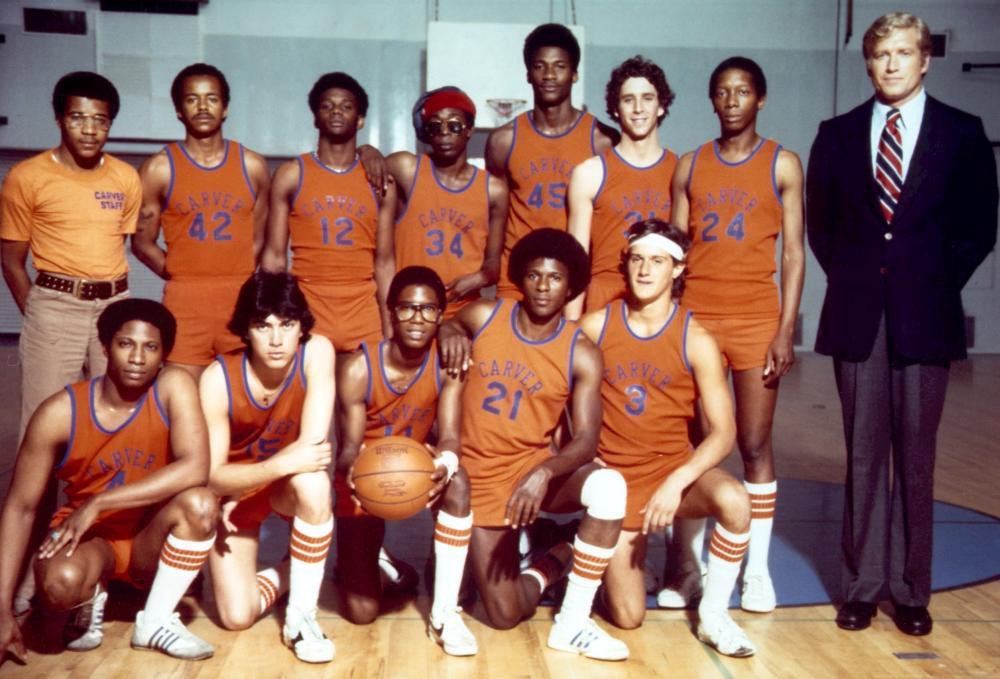

"The White Shadow" (1978-1981)

The TV show that got there first.

I realize it’s tedious for you to read a list of the “real-life” subjects that “The White Shadow” tackled in its fifty-four episodes — racism, alcoholism, drugs and overdosing, wrongful incarceration, gang violence, family violence, student violence against teachers, student sex with teachers, teen pregnancy, teen death, STDs, homosexuality, interracial dating, autism, and so on — but I must list them in order to make this point: “The White Shadow,” which began its prime-time run on CBS in 1978, usually got there first.

“The White Shadow” starred the white actor Ken Howard, then known largely for his stage work (in 1970 he got the best featured actor Tony for Child’s Play) , as Ken Reeves, a former Chicago Bull whose career-squelching injury led him to a job coaching basketball at an inner-city Los Angeles high school. CBS requested that the show skirt topics like sex, drugs, and criminal behavior. Bruce Paltrow, the tough-talking liberal New Yorker who created the show from an idea spun with Howard, threw CBS a bone — an occasional scene of the Carver basketball team’s wholesome, “Glee”-flavored a cappella sings in the locker room shower — and then proceeded to ignore everything the network said.

American television has always tried to keep pace with the direction of film, which by the 1970s had given Technicolor romances the kiss-off in favor of gritty realism courtesy of so-called New Hollywood. It was now time for America to see the inner city without punch lines — we had “Welcome Back, Kotter” for those — by way of television’s first prime-time drama with a predominantly black cast.

Most “White Shadow” episodes revolved around hard choices the kids had to make, and suspense was assured because, as regular viewers knew, the show didn’t tend to deliver an uncomplicatedly happy ending. In timeworn showbiz fashion, some of the teenage characters were played by actors halfway to fifty, but the performances were so convincingly juvenile that you rarely noticed. The censors allowed no obscenities or explicit sexual references, but one kid might tell another that he saw his grandmother naked — that sort of thing — and it got the spirit across.

If something resembling authentic competitive camaraderie comes through in the locker room scenes, that’s because it was really there. Timothy Van Patten, who played the team’s Italian American lunkhead, Salami, and who, incongruously, went on to direct episodes of smart-person shows like “The Wire” and “Boardwalk Empire,” said in the DVD commentary, “We had our own secret language — we really did…Not only that, we would…take every opportunity to beat the shit out of each other.”

The idea, mercifully unarticulated, is that these kids have been sufficiently burned — by school, family, the community, the system — to know that something that looks good should be met with squinty-eyed suspicion. “Listen, what’s your story?” says Hayward, the brain with black pride and crap grades, when he gets stuck sitting next to the coach on an airplane that’s supposed to fly the team to a tournament. “You used to be in the big money. You was a high roller, man. You don’t need this job.”

Well, he does need a job. When Reeves blows into Carver, he isn’t flawed but idealistic like Glenn Ford’s character in 1955’s Blackboard Jungle; Reeves just wants to get by, and maybe laid by the show’s odd romantic interest for him. He doesn’t want to touch the team members’ personal problems. When he reluctantly does, he gives wretched advice — he tells one player to marry his pregnant girlfriend, since this was how it was done in his day — and later hates himself for it.

When Reeves does voluntarily get in the kids’ business, he’s generally motivated by self-interest, as when he tries to talk Coolidge’s mother out of letting the team’s star player leave high school to go pro: “The odds are he won’t make it. Then he’ll be ineligible to play college ball. So then he’s out in the street — nobody and poor. Is that what you want for your son, Mrs. Coolidge?” To which she replies, “He’s already nobody and we’re already poor.” Oopsie. Throughout the first season, Reeves is called out, albeit in 1970s wording, for his white privilege, especially by the school’s black, female vice principal — the show’s reliable feminist voice — and he’s not always deferential. “I’m a little tired of going around here having to apologize for everything,” he tantrums at one point.

But as episodes roll by, Reeves is given moments of clarity. In one episode, Gomez — “the only Mexican in school that’s failing Spanish” — returns to his former street gang because his execrable grades have gotten him kicked off the basketball team. Reeves ends up crashing a faculty meeting (he usually skips them) and explodes, “Gomez isn’t failing Carver; Carver’s failing Gomez.”

Paltrow and Howard were clear-eyed from the start about not making the Coach Reeves character “just another white knight coming here to save the ghetto,” as one team member puts it. This is where Thomas Carter, who played Hayward, pulled a second shift. In the DVD commentary, Howard says of Carter, “I think he was very concerned about how the black players would be shown, and what the show was doing, what it was saying. So we very much included him, Bruce and I, in all of it. Like, you know: ‘Are we bending over backward one way or the other?’”

Watching “The White Shadow” today, it’s impossible not to think of season four of “The Wire,” which centers on Baltimore’s crumbling public schools and a failed white cop’s skittish attempt at a new career as a teacher. It’s also impossible not to sorrowfully marvel that, nearly forty years on, “White Shadow” doesn’t seem dated outside its sneakers and shorty-short gym shorts: we’re still talking about what a wreck inner-city schools are, what a blight to the community drugs are, what a tragedy urban violence is.

Things hadn’t gotten better for the kids by the show’s end, in March of 1981, less than three seasons in, but they had gotten whiter. Timothy Van Patten told the Archive of American Television in 2009 that Paltrow was constantly fighting network pressure to make the show less black. In 2013, Thomas Carter, who directed a few episodes and went on to a successful career directing feature films and TV, told the Archive, “I felt like the network kept pushing the show more into a comedic direction…All of a sudden this show that had all these black kids, the ratio was changing, and so there were more and more white characters. And I thought, well, the show’s losing the flavor of what I thought made it really original.”

In her 2014 book, Eat, Drink, and Remarry: Confessions of a Serial Wife, the writer Margo Howard, who was married to Ken Howard during the show’s run, says that Newton N. Minow of the Federal Communications Commission, who famously called television a “vast wasteland,” loved “The White Shadow,” and that Frank Sinatra did too. So did I, and so did the METCO kids at my school in Newton, Massachusetts. So did at least some of the Emmy people, who gave the show a nomination for best drama series in 1980 and in 1981. But it never had much in the way of ratings. Thomas Carter told the Archive of American Television, “Honestly, I think CBS didn’t know what to do with the show, and I think they sort of ruined the possibilities of the show because they moved it around a lot on the schedule.” “The White Shadow” didn’t survive a third-year scheduling change — it got yanked fifteen episodes into its third season.

I haven’t come across “The White Shadow” on any best-of lists, although Mike Post’s funk-tastic theme song gets its due. The show’s only mention in the fall title TV (the Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time is in a “Best Teachers” sidebar; Coach Reeves is number four. Of course Shadow was name-checked in every obituary for Ken Howard this past March. Bruce Paltrow, who died in 2002, is probably better known for his contributions to the long-running drama “St. Elsewhere,” which succeeded “The White Shadow,” and for his own white shadow, his Waspy-looking actress daughter, Gwyneth.

In one of my favorite scenes, Coolidge and Jackson, who are black, listen as Hayward quizzes Gomez in history; they’re trying to get his grade up. When Coolidge and Jackson each suggest that the correct answer is the president he is named for, Hayward tells them, “That ain’t your real names, anyway.” Coolidge says, “What do you mean, that ain’t my real name?” Hayward tells him, “I mean…you figure it out.” Like every other challenge presented on “The White Shadow,” that was for you too, home viewer: figure it out. Mr. Kotter wasn’t going to ask that much of you. But then again, unlike Ken Reeves, Kotter didn’t get fired in the middle of his third season.

You can watch all three seasons of “The White Shadow” on Hulu.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She has also written for The Awl about Desi Arnaz’s autobiography and the unfairly forgotten film Dear Heart.