There and Back Again

Why aren’t there more famous black sci-fi authors?

A few months back, the Fireside Fiction publishing company, released a comprehensive report detailing the lack of black authors being published in speculative fiction. Of the 2,039 stories that American science-fiction and fantasy magazines published in 2015, only 38 were written by black authors. More than half of the publications amenable to speculative fiction (a blanket term encompassing sci-fi, horror, and fantasy works) hadn’t published a black author that year, period. So the numbers pointed to calculated, institutionalized racism (hardly unfamiliar territory for the spec. fiction community), but, as usually happens, it was very important for a couple of days. People were capital-S shocked. Commitments were made. But then the static set in, and the literary world turned to complacency, and as generally happens, everyone forgot.

I grew up with speculative narratives lying all over the house. We were a middle-class black family living in a mostly white southern suburb. The wooden bookshelves sank under the weight of Frank Herbert and Stephen King and Brian K. Vaughan. Whole corners of whole rooms were stuffed with Timothy Zahn’s serializations. Susanna Clarke’s tome, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, occupied our coffee table. Whenever we had acquaintances over, they’d pick it up and flip it around and maybe bop their kids on the legs with it. And when company left, and the dishes were washed, and we were left to ourselves, my father would grab a tome by its spine, and my mother would settle across from him. I imagine the books were a respite from that monotony, and the codification of suburban blackness, and needing to be a certain kind of way: they were a reminder that, against all odds, the universe was ours to take. Whole corners of it had yet to be explored. We could be the ones to do it.

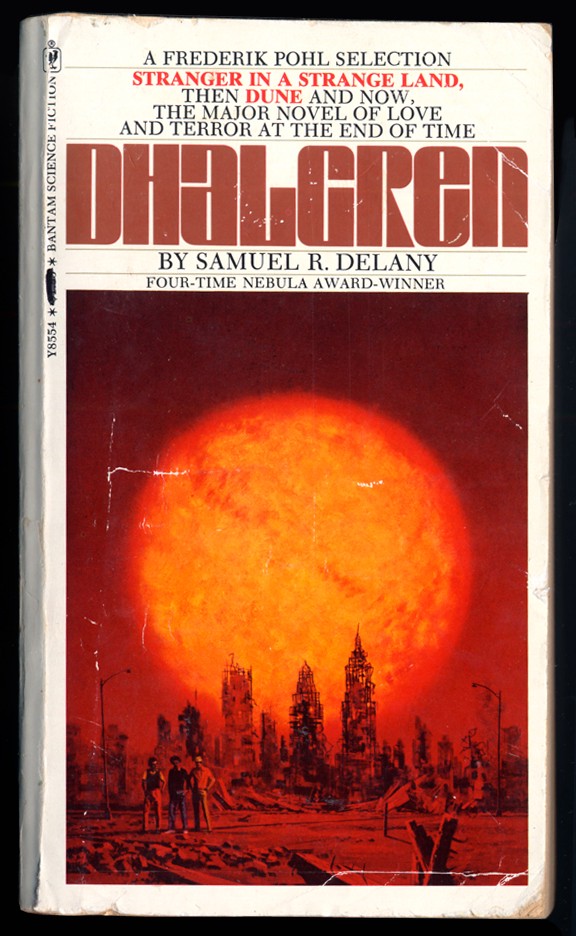

But none — not one — of those speculative authors on our shelves was black. I’d already moved out and left that little town and picked up books and put them down before I stumbled across a novel called Babel-17, in the dim basement of a dank downtown library. A black man wrote that book, his face spanned the entirety of the back of the dust jacket. I was completely flabbergasted. The thought of Samuel R. Delany’s even existing literally scrambled my brain. Delany had written loads of things, and much has been made of his being black while doing so, but I’d never heard of him, and he hadn’t existed to me until I found this interview months later.

Samuel R. Delany, The Art of Fiction No. 210

There’s a passage in the Paris Review piece that sticks with me:

Science fiction isn’t just thinking about the world out there. It’s also thinking about how that world might be — a particularly important exercise for those who are oppressed, because if they’re going to change the world they live in, they — and all of us — have to be able to think about a world that works differently.

I can’t explain how gratifying it felt to read that. I hadn’t seen any black speculative authors, so I didn’t think they were around. But here was this man telling me that not only were they out there, their experiences were a viable part of our universe’s functionality. Reading his words felt like being given permission to do something that hadn’t ever been an option before.

This isn’t to say that my experience with speculative culture had been completely bereft of dark bodies: I’d seen Lieutenant Commander La Forge, and I knew a little bit about Lando, and of course we’re all at least peripherally aware of Storm. I’d seen Blade parade across TNT, and Morpheus monologue in the theatres. I’d fawned over Zack. I’d walked out halfway through Cat-Woman. But it is one thing to see yourself on a leaping and shouting on a screen, and a whole different other to find yourself on the page in front of you. We were hardly in the books, and we certainly weren’t gracing their spines. The case remains largely the same in 2016.

American literary fiction, already an “other” within the business of fiction itself, consistently and predictably demonizes the minority entities within it. This isn’t exactly breaking news — we’ve arguably constructed an entire medium out of those very receipts — but what’s actively distressing is the aggression aimed at anything even skirting the notion of writers of color working within genre. If their narratives aren’t written in a supposedly “exotic vernacular,” reporting live from el barrio, or delivered with the express — but never too tempestuous — intention of conveying “digestible” outrage, minority authors often have a hard time getting a foot in the door; so to pen a piece set on another planet? In another galaxy? Navigating that market is, to put it lightly, a long-shot at best.

In some (most) supposedly literary circles, deeming the work of a supposedly literary author as genre is an assault in itself. There are occasional exceptions: an author already acknowledged as “literary” will be given a pass. Michael Chabon’s The Yiddishmen’s Police Union was one. Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude served as another. In 2014, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven carved a sub-genre were there was none before and Claire Vaye Watkins’ (lovely) Gold Fame Citrus fell into the same boat. But no black authors have been heralded for breaking that barrier yet.

It isn’t that they don’t exist: Nnedi Okarafor, Walter Mosley, Geoffery Thorne, Chris Abani, N.K. Jemisin, Victor Lavalle, and Carl Hancock Rux have been pushing out work for decades. But theirs books aren’t gracing the syllabi, and they aren’t being showcased with primetime reviews, and the press hardly rewards black authors equally in the best of cases, let alone through via speculative narratives. And it shows in the culture.

In an interview with Tor, Okarafor noted that fixing this discrepancy is a work in progress:

I think speculative fiction has fewer unspoken prerequisites than literary fiction for writers of color. I believe this is because 1.) Writers of color have a weaker foundation in speculative fiction. We are gradually creating a foundation. Thus, for now, there are few expectations. I think that will change. 2.) The nature of speculative fiction is to speculate, to imagine, to think outside the box. Speculative fiction is by definition better at doing this than literary fiction.

Daniel José Older, in a conversation with The Rumpus, pointed out that one of the chief causes is America’s reticence at large:

I think it really does connect to the fact that in 2015 we still need a movement to remind Americans that black lives matter. There is a question of relatable characters of color to a white industry, and it’s in the same conversation regarding white carelessness of black lives institutionally, and personally. When you read the tweets and see the video of the cop saying “Fuck your breath,” and all these other things that are happening, they’re all interrelated. They’re all not necessarily the same thing, but they’re interrelated, and it’s about looking at and asking about the empathy gap in whiteness that can’t conceive of the humanity of color. It’s about looking at what’s going on with whiteness there.

Both authors are right. The space for black authors in speculative fiction is continually being built, while the existence of those very spaces is still being challenged by their gatekeepers. And of course we plan to overcome those setbacks, to have a shot at constructing stories that capture the possibilities of everyday life. But these expectations are hardly asking too much as Octavia Butler conceded in a conversation with Charlie Rose: “Do I want to say something central about race except, Hey? We’re Here?”

There’s a moment in this novel, Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, that comes to mind:

Everyone has a time machine. Everyone is a time machine. It’s just that most people’s time machines are broken. The strangest and hardest kind of travel is the unaided kind. People get stuck, people get looped. But we are all time machines.

Because that’s the thing: everyone has the capacity for the fantastic within them. There’s no skin-screening to determine eligibility to make up stories, and it doesn’t matter which rung of our fictitious canon you’re writing from, but this is a statement accepted unanimously and emphatically circles until you emphasize that black people fall under it, too.

That’s when the question turns to qualifications and degrees. It’s when we start getting asked who gave us the right to be different. In his introduction to 1996’s Best American Short Stories, John Edgar Wideman puts that difference on its rightful pedestal:

Stories that don’t acknowledge the mystery at the center of things, don’t challenge the version of reality most consenting adults rely upon day by day, are stories that disappear swiftly into the ever-present buzz of entertainment. Stories that do mount a challenge to our everyday conventions and assumptions stir my blood. Not only because they are exciting formally and philosophically, but because they retain for fiction its special subversive, democratic role.

Reading Babel-17 opened other doors in my head. It was the work that made the existence of other realms even plausible. For some people it could’ve been the most recent Star Wars, and for others it might be this Ava DuVernay adaptation of A Wrinkle In Time that’s on the way, but the fact remains that these adventures still need to make it onto the page.

Because canons are constructed for the emergence of new narratives, and they don’t have to play out on a plantation in Georgia. Or a diamond field in Sierra Leone. Or a dark corner in some unnamed inner city, whose residents actively, notoriously, suffer from every conceivable calamity. And, despite whole industries working against us, we are seeing some progress: we’re watching princesses and presidents and hackers and mathematicians. Whole generations are being re-introduced to the world of Wakanda. We’ve even unearthed Creed. We’re making moves because we have to, because stories are what remind you that you’re really alive.

But there is also room for black voices in parallel universes. There’s room for black voices in the future. The space will be there for as long as we have the people here to fill it. But despite the opposition we’re facing in carving it, or perhaps even because of it, we’re already living in that future.