Death, Sex, and Dinner Parties

Salvador Dalí’s Surrealist Cookbook

A six-year-old Salvador Dalí dreamed of being a cook. We are told this in the introduction to his cookbook, Les Diners de Gala, a collection of recipes unlike any other. His love of food continued throughout his life, and he liked to throw extravagant dinners, where the weirdness of the food matched the crazy, beautiful, messed-up paintings the artist created. I was only able find a record of one of these meals: In 1941, Dalí threw a dinner party in the Hotel del Monte, California, to raise money for European artists fleeing the Nazis. He served live frogs to Bob Hope, and gave him fish in a stiletto heel, while his wife Gala fed Babou, his Ocelot, something resembling vodka. While there are no live frogs in Les Diners de Gala (there is a very dead frog on the front cover and frog pasties later in the text) the book throbs with deliberate oddity.

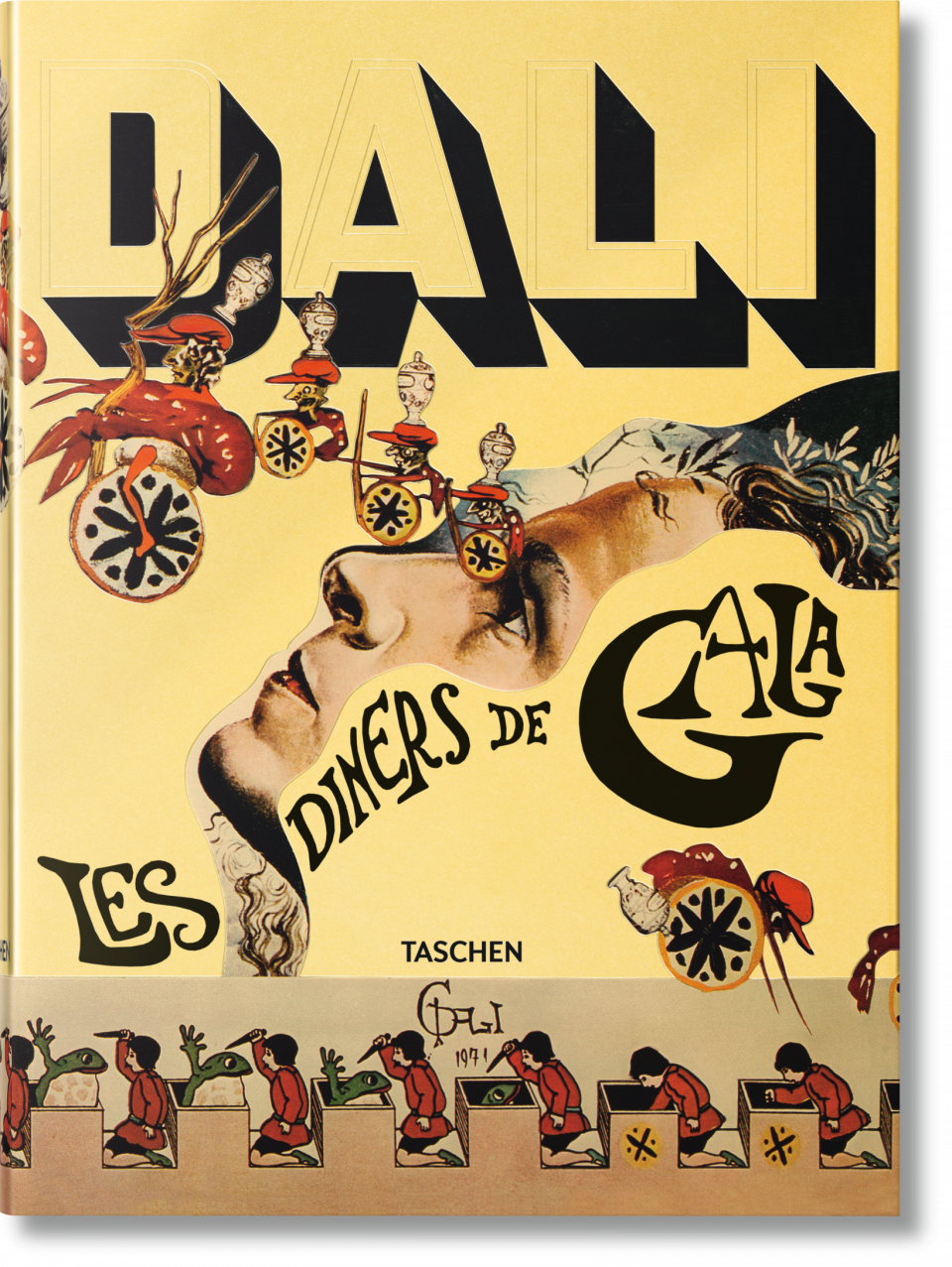

When I was a young child I wet myself on one of Salvador Dalí’s iconic lip sofas in the Espace Dalí, Montmartre. How I was able to get onto the sofa, I don’t know. Last weekend, Dalí had his revenge. I attempted a dinner party following some of the recipes in Les Diners de Gala, recently reissued by Taschen. Published in the 1970s the elaborately illustrated book shows Dalí in full showman mode, as he serves fearful but polite guests elaborate feasts from his home in Cadaqués in northern Spain. These could have been created for a photoshoot, but the food looks real enough, as do the guest’s expressions of meek panic.

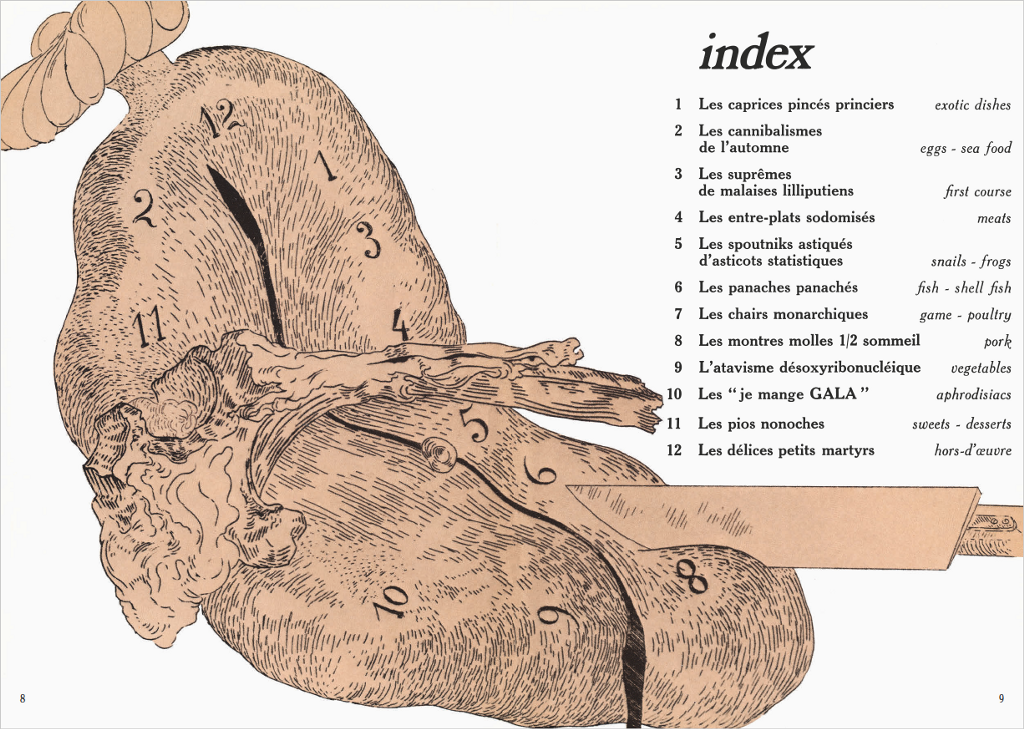

While the book does not tell us the stories of Dalí’s own dinners (the images are left to speak for themselves) we learn much about his attitudes toward food (odd and very tied up with sex, unsurprisingly) and the restaurants he admired. He was a huge fan of Parisienne restaurant Maxim’s, whose menu he faithfully recreated with Salade Alexandre Dumas — containing, according to Dumas ‘great imagination, composite order, slices of beet, half moons of celery, minced truffles, rampion with its leaves and boiled potatoes’ as one of the courses, a meta nod to a French author of The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, who like Dalí, wrote a cookbook. I wondered if Dalí envisioned his own creations one day appearing on some menu — Mexican Baby Turkeys a la Dalí, or Aphrodite’s Puree. There was something weird and wonderful about such a book, so I requested a review copy and set a date for a dinner party.

Dalí’s brand of surrealism about fun, but there was also something darker at play. As a child, he pushed a friend off a bridge with a five-meter drop, then sat calmly eating cherries. As an adult he spoke about this, alongside his obsession with throwing himself downstairs. He was first attracted to Gala whose full name was Helena Deluvina Diakonoff, who was married at the time to his friend author Paul Eluard, when she said ‘I want you to kill me,’ He would go on to marry her. He once asked the art critic Brian Sewell to masturbate in fetal position in front of a statue of Christ.

“He liked to cretinise people,” surrealist painter Genia Chef told me in a phone interview, ‘if you approach [Les diners de Gala] too seriously, you become the victim of a bad joke. It is like his paintings, a sort of art performance. It is truth, but it is a special surrealist truth. It was a joke, but not a joke, you know? Like with his painting, Dalí never made fakes.’

I thought Dalí’s book would be the perfect antidote to the glut of aspirational cookbooks churned out in the last decade — their authors were beautiful and the food sumptuous, but there are only so many ways a model can cook quinoa. There’s just something so affected about the whole thing. Dalí, of course, was the personification of affectedness, but in a different way. I’m reminded of Joe Bell’s assessment of Holly Golightly in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. “You’re wrong. She is a phony. But on the other hand you’re right. She isn’t a phony because she’s a real phony. She believes all this crap she believes. You can’t talk her out of it.”

The cover of Les Diners de Gala is a triumph of gothic bling, adorned in the gold I associate with pharaohs’ tombs, and illustrated with half a face that has gremlin unicyclists riding from the eye sockets toward a grumpy-looking prawn. A comic strip around the bottom shows a child stabbing a frog as it emerges from a box, only for it to pop up, unmaimed and affable a moment later.

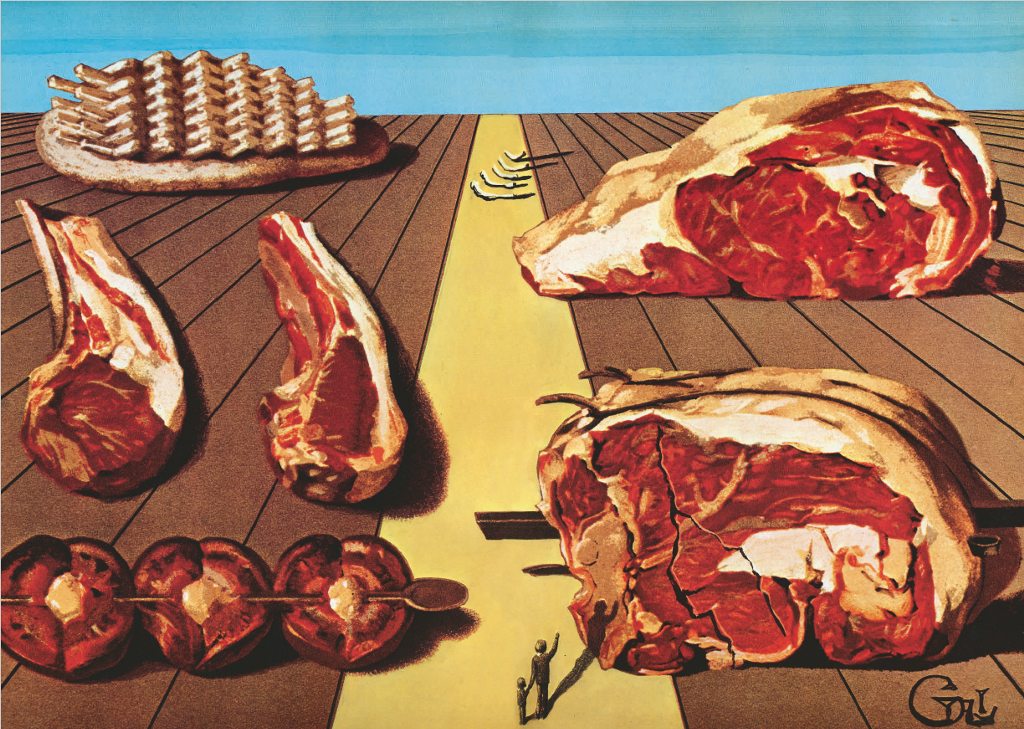

Besides food, Dalí was obsessed with, death, sex, and Catholicism. When introducing the meatiest section of the book, Dalí wrote, “The specter of death creates supreme delights, salivary expectations, and this is why the greatest of gastronomical refinements consists in eating ‘cooked and living beings.’” For Dalí, the connection between food and death was a beautiful thing; he saw the deaths of the animals he ate as a stage in the journey to his own. He cites a sixteenth-century apothecary — Theofastus Bombastus Paraclus, who was reportedly the inspiration for Faust — who said that “digestion was a combustion leading to death.”

But did Dalí really believe this? On a visit to Britain he visited a diving shop to be fitted for a suit, and when asked by the shopkeeper where he intended to dive, he told the man he wished for a suit to allow him to delve into the depths of the human subconscious, bringing a troll-like literalness to the theories of Freud and Jung. So was he a charlatan, a mad man, or in the words of Joe Bell, a real phony? In explaining the presentation of one dish he makes a passing aesthetic reference to a fifteenth-century child-murderer:

The Crayfish of Paracelsus has to be served along with the heads, or torsos, of small hot-bloodied martyrs as a homage to Gilles de Rais whose most delightful ejaculations were brought about by gazing at the dying faces of his smooth-cheeked and innocent beheaded little ones, the virginal purity of whom could only have been compared to that of his former comrade at arms, The Maid of Orleans [Joan of Arc]

Even as a joke, or deliberate provocation, there is something frightening about this casual reference to infanticide. Had it been presented with more fanfare, as opposed to as a throwaway aside, it might have been less weird. But stumbling across it in the introduction to a chapter felt like tripping over a fake but lifelike corpse at a party — not really funny, and sick enough to make you regard your host with caution.

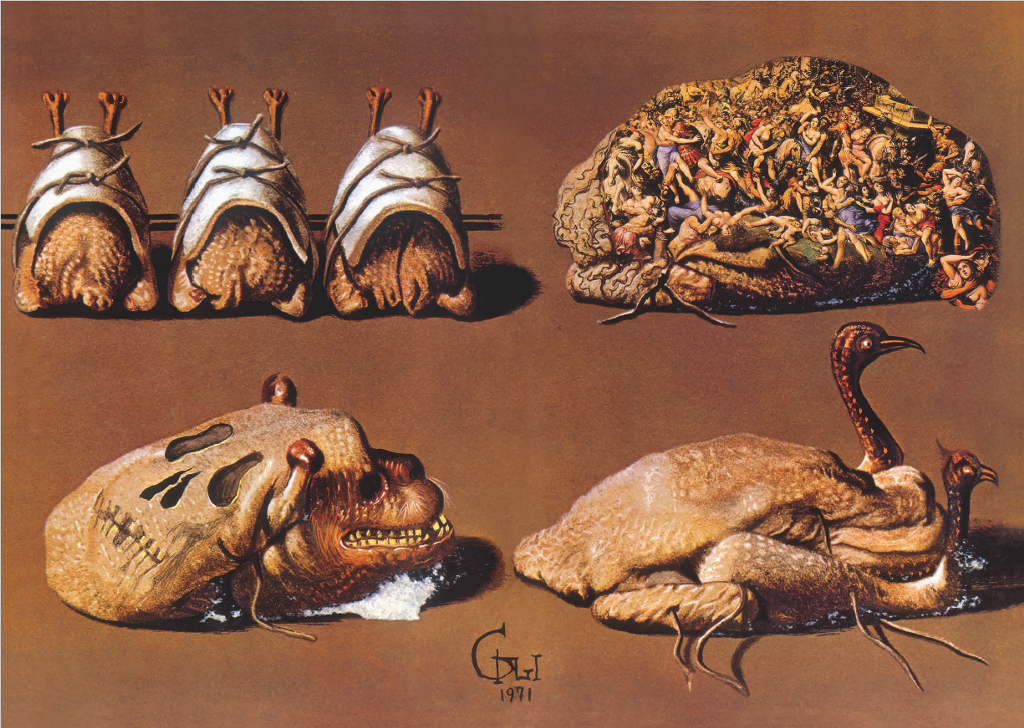

Les diners de Gala is maddening — at one point I felt overwhelmed by the task of feeding my friends from it, as though I was being trolled by a madman who likes to make food difficult to eat (and even more difficult to prepare) for the fun of knowing that someplace, one day someone will try these recipes and freak out. But there is a grim genius to it, complemented by Dalí’s weird illustrations: a chicken with teeth at the front and a ghoulish face in its skin, a pelican-like bird served to be eaten with the mouth and teeth of a gorgeous starlet, a melting clock reimagined as a chopping board.

The book is filled with recipes that call for offal — lungs, heads, brains and tongue of various beasts make an appearance. As a few grim diseases put an end to a consumption of brains, I decided not to hazard these — though a friend suggested I bribe a local butcher. One recipe in the index reminded me of the aspirational cookbooks I came to regret shunning Avocado Toast. The familiarity of it filled me with relief. Then I discovered it called one raw lamb’s brain.

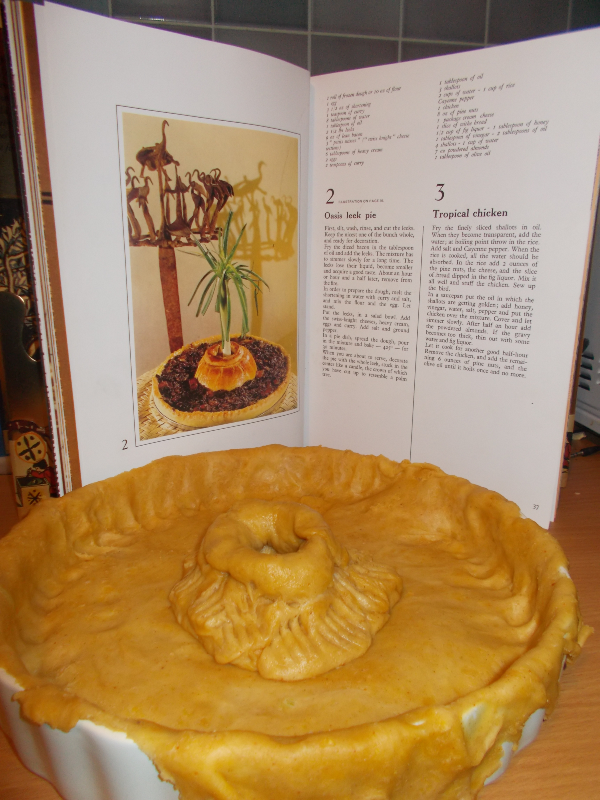

Another recipe, Leg of lamb shot with Madeira sounded okay. “Shot with” often means “with a shot of”; however, this recipe literally asks you to inject the leg of lamb with a veterinarian-gauge syringe. I only received a hard copy of the book on the same day I was to cook, so a syringe was not easily obtainable despite my being in Edinburgh, the city featured in Trainspotting. I felt it was unlikely that any of the shops would sell me one without deep questioning. I chose instead to cook Oasis Leek Pie, Tropical Chicken and Exploding Mussels.

The Oasis Leek Pie looked easy enough: a quiche with a leek exploding like a firework from its center. The leek, cream and bacon filling would have probably been nice, had it not included curry powder, which tastes really odd when mixed with bacon. The amount of cream (6 tablespoons) and cheese (three petite knight cheeses) and was mildly terrifying. Dalí does warn the reader, “Les Diners de Gala is uniquely devoted to the pleasures of taste — if you are one of those calories counters who turns the joy of eating into a form of punishment, close this book at once.” He also rails against spinach: “If I hate that detestable, degrading vegetable spinach, it is only because it is shapeless like liberty. I attribute capital esthetic and moral values to food in general, and to spinach in particular.” (Here I feel confident that he is being genuine. Dalí did not seem like a man who would have believed in low-calorie diets. Similarly, it is likely that he did attribute moral values to food in the same way that modern food-writers talk about free-range, paleo or vegan diets.)

The relatively sane Oasis Leek Pie turned out to be difficult. The pastry bit in the middle designed to hold the leek looked really weird kind of like the crater of a volcano you’d make from plasticine in primary school, however and I wasn’t sure how to make it. My flatmate Vicky, who is more dexterous than I, ended up taking over the crafting of the ‘leek holder.’

“Do you think it’s meant to look like a vagina or?” she asked. I thought it looked more like a rectum. I opened the discussion up to our guests, who on balance, thought it had something vulvate about it. I was pleased that this was the first time I had made successful pastry dough — Dalí’s recipe, with shortening rather than butter, works excellently — but annoyed that I had to fill it with the curried leeks, cream and bacon. As far as how the pie tasted, one friend went as far as saying it was “actually almost nice,” while another compared it to, “coronation chicken, but with bacon instead.”

The tropical chicken filled with rice, shallots, pine nuts and cayenne pepper was also okay, though I used figs as opposed to fig liquor as I was unable to source it. It would have probably been nicer with this addition, but the chicken was extremely edible, and nothing like the ghoulish chickens featured in the book. This was real food, with nothing surreal about it; if anything my guests were disappointed that it wasn’t any weirder.

Dalí’s paintings hold extreme beauty, even if no one can figure out what they actually mean — he rejected hifalutin analysis when asked whether his melting clocks were a response to Einstein’s theory of relativity, replying no, they were melting Camembert cheeses. Some of the recipes in Les diners de Gala are sumptuous and beautiful, designed to give pleasure to the senses, as opposed to just confusing the hell out of you. The Mussels Surprise is designed to astonish, rather than horrify. “Your guests will be flabbergasted to see the mussels opening up spontaneously,” wrote Dalí.

Prying open thirty six mussels and tying them with string however is far from easy, and I had my doubts as to whether they would be cooked properly. In most recipes a mussel opening or not opening is the means by which you tell it’s safe to eat. I beseeched my chef friend, David Bakermault, to help prepare them so as not to poison any of my guests, though by this stage I thought Dalí would applaud if I did, perhaps writing something long-winded about the little-known merits of vomit by way of congratulations.

We presented the mussels in a bowl with jelly lip sweets; a homage to Mae West and the sofa I peed on when I was four. They looked beautiful. My friends too, looked gorgeous in their surrealist costumes. Rik was delighted to have reason to wear his red velvet suit jacket, while Johanna dressed as the October day, half wet, half dry — on one side her hair dripped, on the other it was blown as though by the wind, though as the night progressed she had to run to the bathroom to dampen her ‘wet side’ several times. As we sat down to eat, and to drink absinthe, my panic dissipated, and I thought maybe the book was okay. Unlike Babou, who was seemingly fed alcohol in the footage of Dalí’s 1941 party, our cat—our stand-in ocelot—was not given any booze.

I even considered holding another party and thought about where to buy a veterinarian-sized syringe. Ultimately, Dalí was, like Golightly, a real phony. He believed much of what he said, and the things he said to horrify, to get a rise out of people, to drive you insane as you pry mussels open with a knife, these too were real insofar as he wanted to provoke, not in a phony way, but to make people think. What did he want us to think though? I’m still not sure. The cat dragged off the remaining chicken carcass, necessitating a thorough search the next day until we located it in the boiler cupboard. I got the feeling that Dalí would have approved of this, as he would of my own accidental prank in Montmatre.