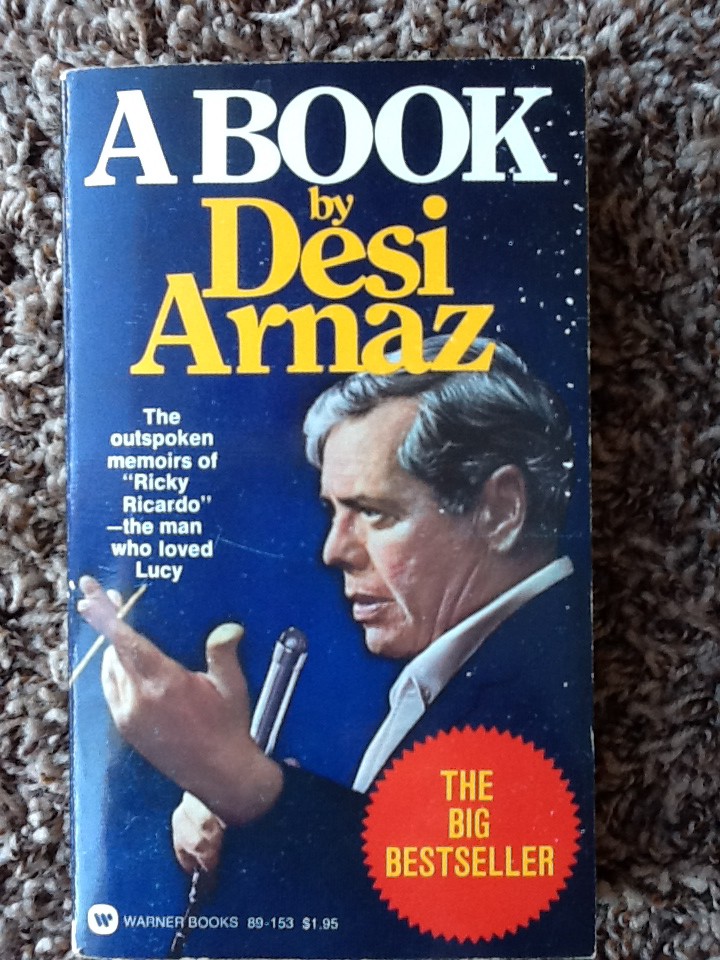

'A Book' by Desi Arnaz (1976)

The “I Love Lucy” star’s best-selling autobiography.

The first thing you notice about “I Love Lucy” after it’s been off your radar for many years is how damn good it is. The second thing you notice, if you can listen past Lucille Ball’s earsplitting tantrums and look past her eye-splitting mugging, is how good Desi Arnaz was.

I completely missed Arnaz the first time around, so I paid attention to him a few years back, when my daughter and I were plowing through the series. What he was doing on-screen was deceptively complicated: holding his own against Lucille Ball, building a sympathetic killjoy character, making you believe he would never divorce his lunatic wife, and keeping a straight face, sometimes while unleashing a logorrheal burst of Spanish. Once the actor had learned not to say “Hello?” before bringing the prop telephone to his ear, he was a consummate television performer.

Arnaz was also a pro when it came to his best-selling autobiography, A Book, which was published in 1976. Two years elapsed between the time Arnaz told his story to a recording device and the time he and his amanuensis completed the rewrites, and the result is a funny, free-flowing narrative that reads like Arnaz shooting the breeze on a talk show (albeit on cable — I counted twenty-odd f-bombs). Beyond its title, A Book has a fabulous meta aspect that gives the reader the persistent sense that there’s no joke Arnaz isn’t in on. When he says “This reminds me of a story about Greer Garson and Jimmie Durant,” you know he knows this is a showbiz cliché.

Nothing about his life was cliché, though. Arnaz was born Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha in 1917, in Santiago de Cuba, where his father was a three-time mayor and later a congressman; his grandfather on his mother’s side was a founder of the Bacardí rum company. That his paternal grandfather was a philanderer Arnaz treats matter-of-factly: “Having two houses and two sets of children was very common among Latin men of means, and Latin women understood this and didn’t make a fuss about it.” Between this attitude and the Bacardí connection, you wish you could have warned Lucy.

When the Batista revolution came to Cuba in 1933 and overthrew the Machado administration (for which Arnaz’s father worked), the family lost everything. Arnaz’s mother hid with relatives while he and his father fled to Miami to try out the fabled American dream. They ended up living in a rat-infested warehouse, where they attempted to get a decorative-tile import business going, but the tiles kept breaking. At one point the younger Arnaz cleaned canary cages to make ends meet. In the midst of poverty, he found pockets of joy: “I’ll never forget those gorgeous nights on the beach, with the moon over Miami. We ate and drank, sang and played, and screwed and screwed.”

Arnaz plinked around with a guitar, an instrument at which Cuban men were encouraged to be proficient for serenading purposes (“You would have a hell of a time carrying a piano,” he wrote). In 1936, he joined a small-potatoes Miami rumba band that played in town. When Spanish rumba king Xavier Cugat offered him a job, Arnaz agreed to join him in New York as soon as he finished high school. He was bedazzled by the wattage at a Cugat show that he was part of in Cleveland: “The stars were Johnny Weissmuller, Eleanor Holm, Buster Crabbe, Cugat, and the Cuban birdcage cleaner.”

After a six-month apprenticeship, Arnaz decided to try fronting a band in Miami, where he put together a rumba group and introduced a signature Cuban dance, the conga line; it became a national dance craze and his calling card. (The gossip columnist Walter Winchell would dub it “the Desi chain.”) But Miami was a small pond, so Arnaz moved back to New York, where the night was his life. He squanders few words on his fling with the leggy pinup gal and movie fixture Betty Grable but spends half a page describing a high-class whorehouse, where he kept company with the madam “and her girls,” who “were my friends, and then some.”

Since this was the American dream that Arnaz was trying out, it was only natural that one day he learned that Rodgers and Hart (“Who?”) wanted to speak with him, as did the legendary theater director George Abbott (“Who’s he?”). Without ever having seen a Broadway show, Arnaz was cast in one: Too Many Girls (“Our whole show was about college kids, football, and screwing”). The first-act finale was rewritten to accommodate his conga line, which was finally taking him somewhere.

In one sense, the fun stops when Lucille Ball shows up about a third of the way into A Book. Arnaz meets her in Hollywood, where they will costar in the film version of Too Many Girls, in which Arnaz was to reprise his theatrical role. From the start, Arnaz and Ball were crazy-jealous and volatile. Arnaz writes, “In later years Lucy would say, ‘Too Many Girls was not only the title of your first show, it is the story of your life.’” When they got hitched in 1940, their friends gave the marriage two weeks.

The couple continued to tread water professionally. Ball reported for B-movie duty (e.g., A Girl, a Guy, and a Gob) and Arnaz did the odd go-nowhere picture (Four Jacks and a Jill), although he was hopeful about the semi-persistent rumblings around town that he was going to be the next Rudolph Valentino. He lost at least one role because of his accent, which three months with an elocution coach could not dismantle. Without much else to do, Arnaz joined the army once his citizenship came through. When he got out two and a half years later, in November of 1945, he reported to MGM, where he was still under contract — rumor had it they needed a Latin lover for an Esther Williams musical. But the role had already been given to the other next Rudolph Valentino: Ricardo Montalbán (more bewilderment from Arnaz: “Ricardo who?”).

Defeated, Arnaz returned to music, which could only mean hitting the road. The geographic distance between Arnaz and Ball fed the already sky-high flames of jealousy: “I would protest that I never fooled around with people I was working with. To which she would answer, ‘Hah!’ But it was true, most of the time, anyway.” Arnaz and Ball seized on the idea of costarring in a television show; they thought being together could save their marriage.

When “I Love Lucy” premiered in October of 1951, the public bought the then-frightful notion of an all-American gal married to a Cuban dude, and scatterbrained Lucy and mush-mouthed Ricky ruled the airwaves for the better part of a decade. Arnaz writes that when the New York Times Magazine asked him to divvy up credit for the show’s success among cast and crew, he said that Ball was ninety percent of it.

I don’t think she was. After “I Love Lucy” ended, Ball spent more than a decade in a couple of unspectacular sitcoms named for her, many episodes of which had the advantage of being penned by “I Love Lucy” writers, and these two shows were worse than “I Love Lucy” by a good half. What was missing was Arnaz. He had had creative control of “I Love Lucy” as executive producer and president of Desilu (Ball was nominally vice-president), and he’d made many clear-eyed decisions. He originated the three-film-camera technique for television shows in order to capture authentic audience reactions, and he insisted on verisimilitude on the set (meaning a real eight-foot loaf of bread came out of Lucy’s oven). But beyond Arnaz’s role as overseer, it’s utterly impossible to imagine that I Love Lucy would be as good a show without his on-screen presence. He added dimension to what might otherwise seem today like a very funny sitcom about a typical (if unusually loud) middle-class American couple at midcentury.

In its last chunk, A Book loses ballast, not unlike Arnaz’s marriage. His recollections of a succession of whiz-bang business maneuvers are what I imagine The Art of the Deal reads like on a good day. During this period, Arnaz was under terrific pressure — playing Ricky Ricardo, producing the show, running Desilu — and his health was suffering. He told his father, “I was happier cleaning birdcages and chasing rats.” He wasn’t seeing much of his kids and was drinking too much: “I guess if I had learned the meaning of moderation and had been able to practice it, the Desilu monster we had created and our marriage might not have been so hard to cope with.”

In 1961, a year after her divorce, Ball married the comedian Gary Morton. Yes, she had moved on, and quickly, but in a Barbara Walters interview from 1977, conducted during Ball’s Phyllis Diller period, she was conspicuously still peeved at Arnaz: “I married a loser before…He was brilliant. But he had to lose…Everything he built, he had to break down. And he still claims he’s the same way.”

Toward the end of his life, Arnaz got sober. Not long afterward, in 1986, the lifelong smoker died of lung cancer, at age sixty-nine; this was one year after he lost his by-all-accounts cherished second wife, Edie. Ultimately, A Book is about nothing less than the American dream and one’s right to thoroughly fuck it up once it’s realized, and then maybe be permitted to get a little glimmer of it back, if only for a short time.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor.