White Noise

Donald Glover’s “Atlanta” depicts young black men with humanity.

“Atlanta” is the blackest show on television. (This is not quite the same as saying that it has the greatest number of black people acting in it, or the most black people paying for it, or even the highest ratio of black-to-not-black writers — which, although probably true, isn’t what I’m getting at). The streets are black. The cinematography is black. The exchanges between characters are very, very black.

It is what Zadie Smith has called the “culturally black meaning” of the word soulful: “feeling transformed into something beautiful, creative, and self-renewing, and — as it reaches a pitch — ecstatic.” “Atlanta” is just black, and not simply for the sake of a bit. Its blackness isn’t maximized as a tool to shock its viewership, with warring record labels and absurdist between scene music videos, and it isn’t casually injected as a prop or a set piece, or an oh-by-the-way for polite evening sitcom viewerships, either.

Donald Glover conceived of the show in 2013, but he was busy: he rapped, he joked, he pulled a man off of Mars. He was on the verge of returning for the sixth season of “Community” before opting out to focus on “Atlanta.” When asked about the three-year gap, Glover merely responded, “That’s how long it takes.” And it shows.

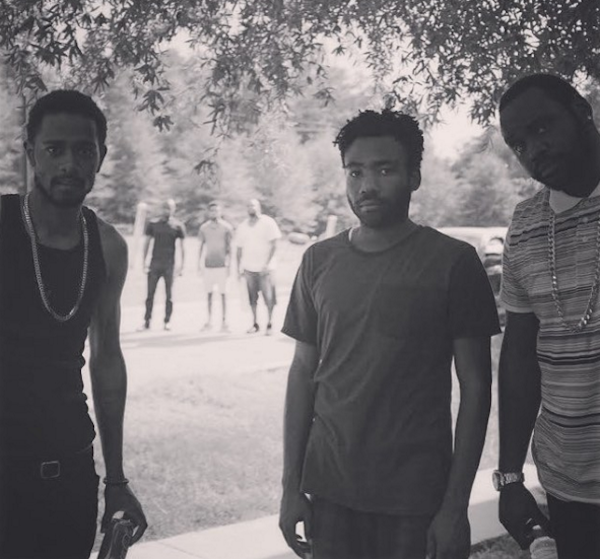

“Atlanta” follows the misadventures of Earn, an accidental music producer, his cousin/client Alfred (aka Paper Boi), and Alfred’s partner, Darius. You could say they’re trying to break into the music business, but that would be lazy. Really, they’re navigating life in the city (although, curiously, I have yet to see a comparison between “Atlanta” and “How to Make It in America,” or even “Girls.”)

They stress over bills. They work shit jobs. They go to jail, and get out, and see themselves on the news. They treat their partners to overpriced dinners and immediately claim credit card theft. They get high on couches, and higher in cars, and highest simply walking from one end of the block to the other. They face vehement and total rejection from their parents, as Earn does in one of the most uncomfortable familial takedowns I’ve seen on television: In a katana-sharp brand of casual contempt black parents have wielded since time immemorial, Earn’s parents dismember relationship status, his joblessness, his lack of education, and digestive habits without even letting him past the porch.

Under Hiro Murai’s direction, all of it is beautiful, but none of it is flashy. There is a lived-in-feeling to each scene, as though these things have happened before, and they will happen again. This commitment to a Lack of Bang is at its most visceral in the first episode: after finagling Alfred’s first major block of radio-play, Earn finds him blasting the track in his car with Darius, both of them bopping deeply to the bass. When the two men finally acknowledge Earn, it’s to extend the joint in Alfred’s fingers and ask Earn if he’d like to partake. Another director may have maximized Earn’s first act of valor with fanfare, or mood music. But here, as in life, Earn thinks before he inhales. He smiles quietly at the invitation.

Critically, the series has done well. Typically unexcitable people are losing their minds. The Economist lauded the series’ “important new voice”, Jezebel deemed it “reliably special,” and the New York Times has called it an “idiosyncratic hangout.” Indie Wire anointed it as “essential viewing.” In the midst of these accolades, the series has just been renewed for a second season.

But it is one thing to account for the series’ reception, and another to try codifying what is actually is. The Daily Beast described “Atlanta” has been described as “primarily a show about hip-hop,” which is both true and not. Mother Jones called it a “take on the African-American experience,” which presupposes that African-Americans are identical, with uniform, indistinguishable experiences, more akin to Cheerios than individual people. But this series, and the entirety of conscientiously plotted network television shows with African-American leads, can be boiled down to this notion: it is the extension of an olive branch into previously uncharted territory. Glover is offering of a joint from a crowded car.

Atlanta may not have been the obvious choice for the setting — surely New Orleans or Philly or Houston could’ve pulled it off — but it is where Glover came up. The show’s specificity is evidence of his affection. It certainly isn’t Tyler Perry’s Atlanta, or TI’s Atlanta, or the Atlanta combusted by the city’s Real Housewives, but Glover’s city alludes to the fact that it contains all of those things, even if it isn’t any one of them in particular. Locals seem to agree with his depiction. But even if the city is cosmopolitan and multifaceted and capable of containing these multitudes, even that seems to be changing rapidly. Its blocks are becoming homogenized. And, as Glover claims, when justifying one character’s use of a highly localized patois, “that dude won’t be around in seven years”.

When black people are on television, it’s either very bad news (they’ve been executed for holding a book, or playing in the park, or reaching for identification) or very good news (they’ve won the presidency or some sort of championship). They are seldom extended the empathy that presupposes them as human beings just living their lives, as elementary school teachers, or dentists, or couples, or violinists, or firemen, or even detectives (with a few notable exceptions). This could largely be the result of a lack of imagination in our writers’ rooms. And that is largely the result of a lack of diversity in those same corners. In a discussion between Ava DuVernay and Q-Tip at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival (another thing lacking: two black people simply talking to each other onstage), DuVernay attributed the absence to a void in entertainment culture: “To say you’re a fan of black filmmakers is to say you’re a fan of two or three films…We don’t have a Woody Allen, or a Mike Nichols.

In a 2015 Rolling Stone interview, Chris Rock touched on the same impossibility:

If someone was going to hand me something like Top Five, I’d be more than happy to act in it…I’d rather work with Wes Anderson, but I don’t look like Owen Wilson. I’d love to work with Alexander Payne and Richard Linklater. But they don’t really do those movies with black people that much. So you gotta make your own. And the black movies of substance tend to be civil rights.

Recounting the production of her 2000 film, Love and Basketball, Gina Prince-Bythewood recalled her own struggle producing a film about black romance with two black people at the helm:

Every single studio turned it down. It was devastating. I remember I had a list on my fridge of all the studios and every day crossing another one off. And I kept getting the feedback that it was “too soft,” which I just didn’t know what that meant, how is it soft? But I think part of it was also it was a film with two people of color in the lead in a love story. It wasn’t a comedy. At that time, obviously there was the success of “Boyz in the Hood” and “Menace II Society” and this was something definitely different. But again, it was what I wanted to see and what I felt we hadn’t had an opportunity to see.

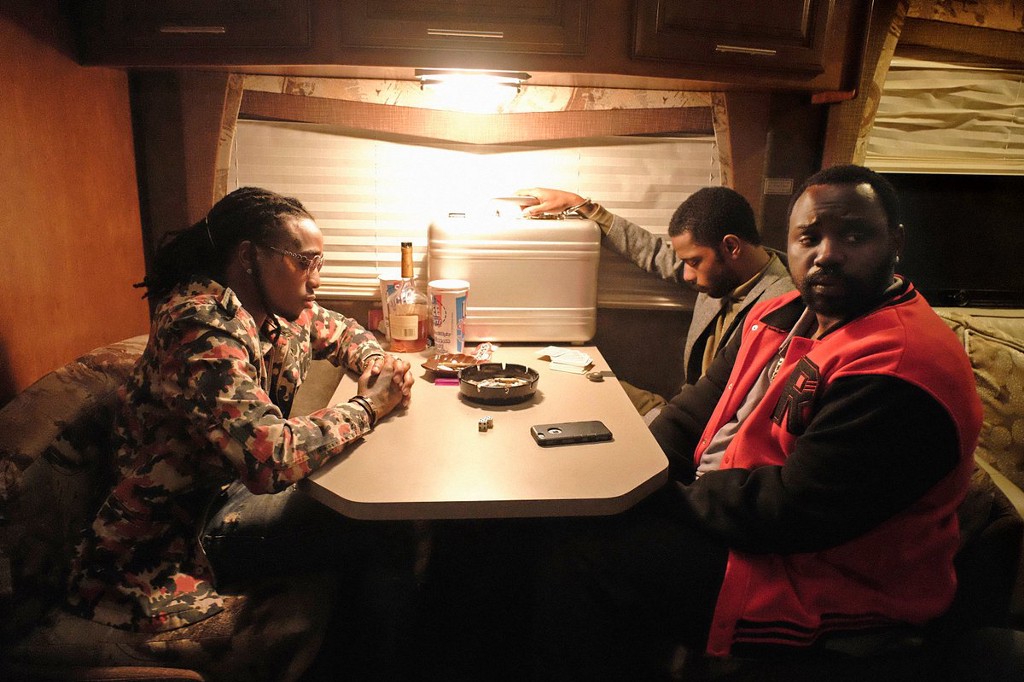

Unless they were cracking a joke or firing a gun, black people on film weren’t identifiable. They were invisible. But if there really is anything unheralded about “Atlanta,” it’s the series’ defiance of that notion — it depicts young black men with humanity. An already rocky date is tipped bassackwards by an overeager waiter, and a pair of young men is blessed at the local hot-wing diner by the jubilance of unexpected lemon-pepper flavored joints with the sauce. They experience the shame and awe when you’ve forgotten the key to your suitcase (filled with drug money) at the apartment, and the consequent relief when your supplier comes up with the workaround (cutting out the money, leaving you with the suitcase).

You could argue that these are too far outside the experience of most viewers to hit home. But they cannot be as far as the conquest of seven kingdoms by dragon-fire, or a subpar execution of the tango in a room of celebrities, or even the day-to-day interactions in an office beside a forever-present laugh-cam. It boils down to a simple, disturbing question: who on television gets to be human?

Glover hints at an answer in a recent interview with Vulture:

I just remember Chappelle’s Show, reading interviews, him being like, ‘We just wanted to make this personal.’ So just let me try and make this show as personal and possible, and not just all the nice and fun stuff of being black all the time.

He isn’t far off from Ralph Ellison, who wrote in an essay entitled “Twentieth-Century Fiction and the Black Mask of Humanity”:

Thus when the white American, holding up most twentieth-century fiction, says “This is American reality”, the Negro tends to answer (not at all concerned that Americans tend generally to fight against any but the most flattering depictions of their lives), “Perhaps, but you’ve left out this, and this, and this. And most of all, what you’d have the world accept as me isn’t even human.”

The first time I ever went to Atlanta, I was eleven or twelve, having been driven up for my cousin’s graduation. Her younger brother was charged with babysitting me, and he took the job gratefully, which is to say: he was paid, and I don’t remember him bitching or sneering or scheming to drop me off in a swamp.

I hadn’t really hung out with black males of a certain age before then; there weren’t just many in my pocket of suburbia. But my cousin was kind and accommodating, and he asked if I was hungry. After stopping for gas, he met a friend, and they exchanged a handshake unlike any I’d ever seen. His buddy joined us, slurring a “What’s good, bruh,” and proceeded to roll a crusting spliff. They passed it between them in the parking lot. An older white woman walked by. She frowned at the car, at us, at in our general vicinity. A young black dude cruised around shortly afterwards. He clapped his hands with my cousin. A gas station attendant, and an elderly black woman, and a gaggle of Latino kids pointed and laughed at the smoke, but whether this was amusing or alarming to my cousin was lost on me because by then they were deliciously above the clouds

They drove me through hilly Atlanta, from the nicer parts of Buckhead to what looked like less nice parts. Then they drove back. My cousin’s friend asked me if I enjoyed playing video games, and when I answered in the affirmative he nodded solemnly, admitting he had no console system. But he’d like to have one someday. Eventually, he’d have the money. We made it to the graduation ceremony a little late, and then we sat in the back.

I had never spent a day like this, did not know it was how people could act. For all of the Culture I’d consumed by that point, I’d have been more comfortable assisting Spiderman down a skyscraper, or diffusing a bomb on a crowded bus. Television and suburbia hadn’t prepared me, and it’d be minute before I had another just like it. “Atlanta” will, if nothing else, make these experiences less of an anomaly. Whether or not people agree to spend more time with Earn and Alfred and Darius is their own business — that’s their call. But maybe they’ll look at the black people in parked cars and across the sidewalk and in waiting booths and in parks just a little deeper. Maybe they’ll allow them a little interiority.