What Does It Mean To "Live Like An Artist" In New York?

On the history of loft living, and its changing definition.

When my twenty-two-year-old artist father moved into his raw loft space in SoHo in 1975, he had to pay an extra $1,000 to get basic plumbing risers installed. The floor was stained with machine grease from the bookbindery that had operated there; there were no walls or partitions, and he slept on a mattress in the corner on the floor. Trash collection was seldom, and basic groceries were a half-mile away.

For the first couple of years, a printing press still operated upstairs, shaking his entire building during business hours.“This is not an apartment!” his family cried. Yet, he never had to take a roommate to make rent. He had the entire space to himself, where he could set up his creative life: print his etchings and work on oil paintings and illustration projects. Sometimes, on breaks, he would pretend he was a baseball player, running around the 1200-square-foot space and sliding into an imaginary third base.

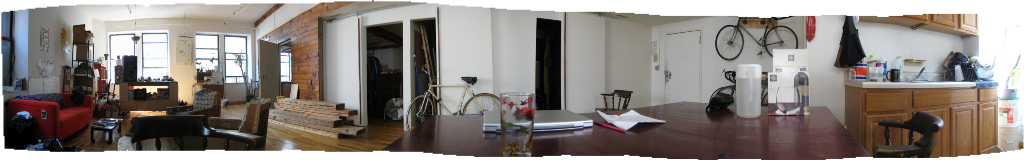

Even while it was still illegal, living in former factory buildings was already ascendant as a “lifestyle.” The average SoHo loft was a cavernous 2,100 square feet; taking up space was part of the radical project of loft living. In 1970, Life published a photo essay called “Living Big In a Loft,” showcasing the more grandiose pads of various early loft inhabitants, and the freedom that all that space gave them:

Multimedia Artist Bob Wiegand swings from a trapeze he installed in his 2,500 square-foot loft, on the fifth floor of a cooperatively owned building. He enjoys performing acrobatic stunts in his studio, although he admits climbing the 144 stairs from the street is probably all the exercise that anyone needs.

The law lagged somewhat behind. In 1971, the New York State Legislature added Article 7-B to its Multiple Dwelling Law, recognizing that “there is a public purpose to be served by making [these] accommodations readily available for joint living-work quarters for artists … [who] require larger amounts of space for the pursuit of their artistic endeavors and for the storage of the materials… [and] the financial remunerations … from pursuit of a career in the arts are generally small.” This Artist-in-Residence (AIR) initiative, by allowing this residential use, made it possible to legally occupy former industrial buildings by creating special AIR Certificates of Occupancy.

These legalized units immediately jumped in value, and by the 1980s, most lofts were priced out of reach of the very class of people that had transformed their use. As a 1979 New York Magazine article put it, “in a textbook example of the role of art in urban renewal, [artists] were soon followed by the people who are interested in artists (e.g., gallery owners and collectors) and eventually by the people who are interested in people who are interested in artists (e.g., New York dinner-party goers, a vast crowd).”

As the upper classes moved into SoHo, the media portrayed the need for space as supporting a bourgeois lifestyle rather than the original artists’ utilitarian purposes.. Enormous, decadent-looking lofts became a critical component of many popular films set in New York in the late twentieth century, such as Fatal Attraction, Hannah and Her Sisters, Ghost, and especially Big, where the man-child protagonist bounces on a trampoline in his loft on 85 Grand Street — a perfect setting for sidestepping the conventional requirements of growing up.

Eventually the term “loft” came to describe something more than a physical structure — starting in 1970 with David Mancuso’s invitation-only parties called “The Loft,” and migrating quickly to more remote industries. In fashion, it eventually became shorthand for “bohemian luxury,” starting with the Ann Taylor spinoff LOFT in 1995, which spawned countless aspirational imitators. In 2015, the median rent in SoHo was $3,875 according to the website Zumper. That average includes, of course, all the aspirational listings from newly built or non-loft buildings that can claim extra cachet by using the word.

In industrial Brooklyn, to which the dream of loft living has been displaced, high demand and prices have transformed the prospect of affordable living in New York. Lofts have a particular utility in this, with their open floor plans maximizing space for ingenuity and profit. In 2014, seeking an apartment share, I toured a loft on Bushwick’s Siegel Street. It had a cluster of four “bedrooms,” all of them clamoring for the loft’s single, enormous window. The cubicle-like rooms were stacked on top of each other, resulting in very low ceilings on the top two rooms, which you reached by a handmade wooden staircase. A New York Times Magazine article about a similar loft compared such rooms to horse stables.

Two of the rooms had walls that were partially open to adjacent, windowed rooms, providing some indirect light and air. We spoke about the feasibility of closing off these openings for privacy. Everything seemed to be made out of plywood. (There is more at stake in these situations than just hearing your roommates’ sex and music. A recent Buildings Department violation levied against the infamous McKibbin Street Lofts cites that new walls are made of combustible materials; this is in a building with a history of fire sprinkler problems).

At the Seigel Street loft, we four potential roommates also discussed adding a possible fifth, who would be travelling frequently and defray the cost (unless the landlord, who was proudly showing us the space, would figure this out and charge even more rent.). I am relieved, for various reasons, that this living arrangement never happened.

Many of these arrangements in today’s lofts hearken back to the Wild West or the slum tenements of the nineteenth century, with their overcrowding and constant turnover, as well as their lack of light in many rooms — ironic, considering the usually light-worshipping loft aesthetic. Jacob Riis’s famous photo-survey of New York City tenements wrote of people practically living on top of each other, without the light and air that we take for granted in modern apartment buildings today.

According to the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law, in all buildings built after 1929, “every room… shall have at least one window opening directly upon a street … Every such window shall be so located as to light properly all portions of the room.” The size of windows is also regulated; they are required to have a surface area of at least 10% of the floor area. Though the Loft Law, intended to protect joint living-work quarters for artists, eases up on certain requirements like this, the owners of most Brooklyn loft buildings have not made even preliminary steps to bring their buildings up to code. Thus, many “tree houses,” “cubbies,” and other loft-style bedrooms are dangerously illegal. There is also a 1950s law on the books, albeit rarely enforced, that renders it illegal to live with more than three unrelated roommates.

In New York, Breaking a Law on Unrelated Roommates

In late 2014, I responded to a posting from Alec Henry, a fellow alum from Wesleyan University who was advertising a room in a loft building near the Morgan Avenue L. Though I never got to see the room (someone had already snapped it up), I asked him about the space, which had seventeen rooms and three bathrooms. (Tenement-house legislation in New York from 1867 established a minimum of one toilet per twenty residents.)

“The landlord that we dealt with was actually leasing the floor so the people living there were technically subleasing,” said Henry. “I was in the first group of 17 to move there in June 2014, and I know there’s one or two of the original people still there, but otherwise all new people.” Despite the boarding-house atmosphere, “people did hang out in the common area a lot,” said Henry. “Some good groups of friends developed.”

In this era of mass customization, leaving even small apartments in conventional buildings deliberately unfinished or imperfect — and therefore open to modification, by adding more bedrooms and more occupants — has become more and more common in contemporary apartment buildings. Temporary walls have become a typical fixture of today’s real estate market in New York and are now often built without legally required permits. Stonehenge Properties, which owns twenty-three apartment towers in Manhattan, has been targeting their advertising at recent college graduates, encouraging them to turn one-bedroom apartments into two and three in order to afford rent, because “temporary walls can make room for more roomies.”

During my 2014 bout of apartment hunting, I answered a posting for an individual room in Bushwick’s Tea Factory Lofts, where I was greeted by an eviction notice on the door of the apartment. Not only did this evoke an ugly scene with the prior tenants, but the room being rented out did not yet exist. In the vacant apartment, construction workers were busy building two windowless cubicles adjacent to the one legal, windowed bedroom. The new cubicles, which would have small glass transoms that let in a modicum of light but didn’t open for air, were to be rented for $900 a month.

The Bedford Lofts, a newly constructed luxury rental building in Williamsburg, is an example of this type of marketing gone ironically wrong. According to its website, the property, where a studio apartment rents for $5,250 a month, offers “sumptuous and brightly lit living spaces, dramatic windows, and spectacularly flowing, fine-art-allowing (and often inducing!) open-floor plans… [that] have the power to lift your spirit after a hard day’s work and awaken the deep-seated artist.”

When residents began to move into the building in December 2013, they didn’t realize that a raw open layout was part of the deal; in the four-bedroom that resident Lauren Holman had leased, none of the bedroom walls had actually been built. Leaks plagued the apartment, there were no gas lines, and electrical wires for air conditioning and heat were sticking out everywhere.

When the walls did finally go up, they were built in strange configurations, with one bedroom missing a window entirely. A building inspector visiting the apartment said that if he reported everything he saw, particularly the windowless bedroom, “everyone would have to evacuate immediately.” On Thanksgiving eve 2015, the Bedford Lofts building was completely evacuated for much deeper-seated conditions “imminently perilous to life,” particularly “the installation of substandard structural steel columns, trusses, beams, welds.” This was a far cry from the thick-trussed, brutally strong, industrial cast-iron architecture that had attracted many early SoHo residents.

Despite today’s overwhelming profit motive, a pure type of ingenuity survives. When young inhabitants are able to settle together in one place and stay there for a while, carving out living space by hand can create a sense of creative common purpose. A few loft-dwellers still manage to turn life into art, such as Serban Ionescu, who has taught architecture at Rochester Polytechnic Institute. With his roommates and some funds from their unemployment checks (it was just after the crash of 2008), he built a colorful, fanciful collection of cubbies and bedroom spaces that put most shabby “tree houses” to shame.

“As for living together we grew together, through making art and installations together at first and then to large Parties, cooking, whisky making, cats,” he said.He displays the result as an example of his design work on his website, titling it “The Miner and a Major.”

Unfortunately, without thousands of subpar rooms in existence, many people would probably not be able to gain entry to New York. But the landlord creators of the subpar rooms that are the tickets are occasionally reminded by the Department of Buildings that they are not above the law. The McKibbin Lofts have received violations for illegal subdivisions, lack of egress and even hotel use. Whenever justice is “served” in this way, the evicted tenants, often unaware of the illegality they have stumbled into, are the ones who suffer — uprooted, homeless, sometimes for months. Those already entrenched in loft living need education and leverage against landlord greed.

The ideal of “living like an artist” has deceived some into living in worse conditions than their forebears, whose exposure to grime and precarity once upon a time was at least inexpensive. These days, you might be better off just getting a room in a regular apartment in New York — that is, if you can afford it.

Rachel Pincus writes about technology, design and urbanism. She lives in a “normal apartment” with roommates now and likes it just fine.