What Becomes A Legend Most?

Why some celebrity memoirs are better than others.

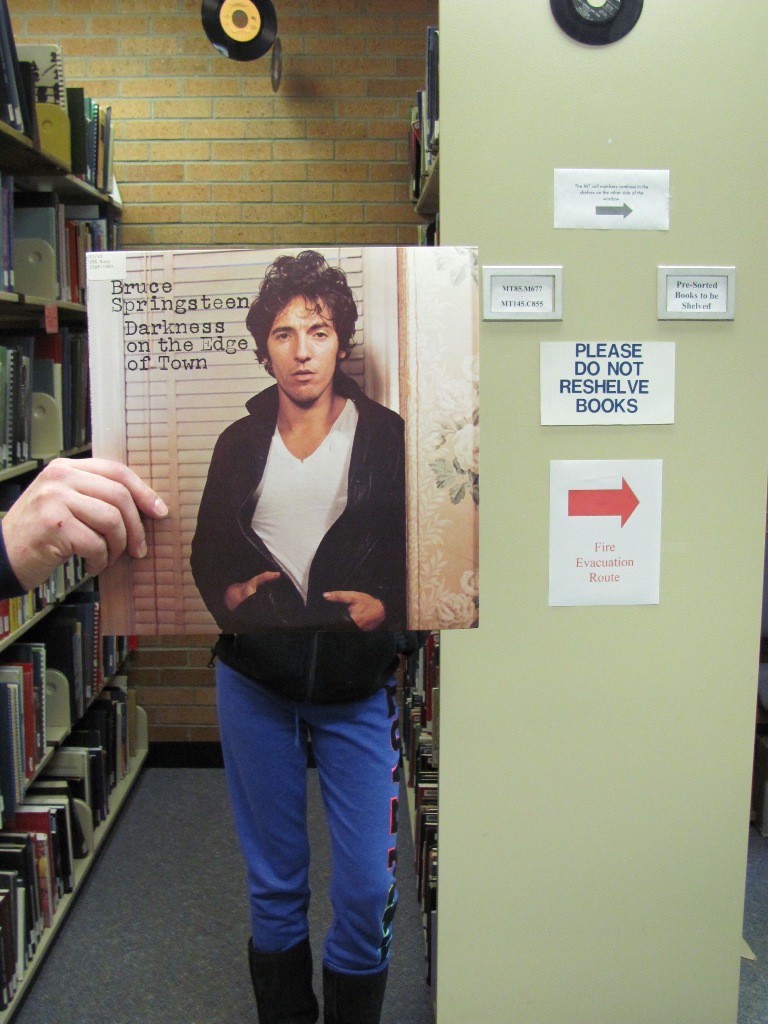

If you thought Bruce Springsteen’s recent record-setting four-hours-plus concert was still not enough Bruce, you’re in for a thrill: on September 27, Simon & Schuster drops the man’s five-hundred-plus-page memoir, Born to Run. Even if you’re not a fan, you can’t reasonably question the book’s existence. Springsteen has had a decades-long stratospherically successful career spent writing and performing songs with lyrics intended to elevate the sorry human condition. Baby, he was born to be read.

If you have a favorite classic sitcom and the star is still alive, dollars to gluten-free doughnuts he or she has written a memoir in the last decade. Wondering what’s on the mind of a member of the rhythm section of your favorite seventies band? If he hasn’t already written a book, he probably has a deal. Of course, there have been celebrity autobiographies as long as there have been celebrities and vanity. But today I don’t think anyone is even pretending that the typical celebrity memoir is what God intended books to be: born of something like an authentic artistic impulse. The recent ubiquity of the modern celebrity memoir raises the existential question, Why are so many celebrities publishing memoirs now? And what makes a good one?

The first celebrity memoir I remember seeing on coffee tables was 1972’s The Moon’s a Balloon (titled for an E. E. Cummings poem) by the suave British actor David Niven. Niven was a raconteur and embodied genteel Englishness, and he knew how to inject the printed page with his charm and wit (sample line: his first sexual conquest had “a figure like a two-armed Venus de Milo who had been on a sensible diet”). So it was possible: literature needn’t be written by literary types. Game on.

I think it’s time for some ground rules: let’s agree that in order to elevate a celebrity memoir above a vanity project, it must have either (a) a great personal story resulting in (or from) a landmark artistic or cultural achievement and/or (b) David Niven–grade turns of phrase. A fabulous story written beautifully would be ideal, but let’s not be greedy: these are celebrity authors we’re talking about.

The celebrity memoir boom partly reflects an adult population that grew up with therapy, self-help books, and other invitations to look within. “There’s too much ‘me’ in Me,” my eighty-year-old grandmother complained about Me: Stories of My Life, Katharine Hepburn’s jeroboam of a celebrity autobiography when it came out to terrific fanfare in 1991. The belief that it’s vulgar to speak endlessly about oneself in public is, like my grandmother, long gone. Now an affront to a reader would be too little “me” in a celebrity memoir; what else are we paying for?

Like Springsteen, Hepburn justified her book’s existence by having led a life without antecedent in her field. Likewise, regardless of what you think of Chrissie Hynde’s 2015 memoir, Reckless: My Life as a Pretender, her book would have had to have sucked pretty royally (which it didn’t; it was a corker) not to have value as a testament to what it was like to be American and female in London’s rock scene in the 1970s.

Naturally, the celebrity memoir phenomenon also partly reflects a publishing industry in crisis: celebrity memoirs lure people who might not normally go to bookstores or check the “Books” icon on their Amazon drop-down menu; the idea is that sales to this demographic will somewhat offset the readership that’s being lost to one screen or another.

But beyond the death of modesty and the publishing industry’s understandable campaign to sustain itself, there’s another force pushing for the celebrity memoir today: celebrities tend to write (or “write”) when their careers are waning or at a low ebb — and note that we have an unprecedented number of celebrities now, what with reality television and Instagram and the rest of it. It’s good odds that when a celebrity produces a book, she is not at the height of her professional powers; otherwise, she would be off acting or being a chef or rocking out. If your star is burning bright, you probably won’t be appearing on Dancing with the Stars, as I felt uncharitably compelled to point out to my teenage daughter, a fan of the show.

But let us have something resembling a heart about this: some celebrities who have peaked (or their publicists) see in a book an opportunity to stay alive in a fickle, youth-besotted business. Before I became a writer, married a musician, and acquired a mortgage and two kids, I didn’t understand the economics of the creative life. I recall being flummoxed when I learned that a member of the Flesh Eaters, a favorite punk band of my adolescence, had quit the band to drive a city bus. Imagine how gutted I felt when Johnny Rotten did that butter commercial. (Loved his book, though.) It’s no coincidence that the celebrity memoir boom is happening at a time when there is absolutely no shame in doing commercials, which is, of course, what the celebrity memoir is: an ad for the self.

If you’re a celebrity who is neither a tested wordsmith nor a Serious Artist, your embossed name can still merit a place on the spine of a book, but you may have to be a little resourceful. Marlo Thomas’s Growing Up Laughing: My Story and the Story of Funny, from 2010, is a memoir interwoven with (good) jokes and transcriptions of Thomas’s interviews with comedians and comic actors on the subject of what makes humor work. I would bet a kidney that Growing Up Laughing arrived at this structure after Thomas submitted a straightforward draft of her life story to her editor, who broke out in a sweat, realizing that he couldn’t publish it as it was due to its adversity-free through line. Growing Up Laughing succeeds as a decent showbiz memoir because Thomas and her book team obviously cared enough about the enterprise to think up a way to enhance what would have been a tale of reader-repellant smooth sailing: the “me” became “we,” which meant multiple little stories in service to the big story of American comedy.

A less enthusiastic effort by a TV sweetie is Amy Poehler’s memoir, Yes Please. As Dwight Garner, a fan of the comic actress, noted in his 2014 Books of the Times review, the guileless Poehler plays her hand in her book’s preface: “I had no business agreeing to write this book” (meaning the idea wasn’t hers). Writes Garner: “Ms. Poehler’s slow drip of gripes (‘Dear Lord, when will I finish this book?’) breaks rule number one about comedy and about writing: Never let them see you sweat.” Garner gives Poehler points for honesty; I give her points for having apparently undertaken the book without a hired hand. (After all, talking into a recording device is writing the same way that listening to an audiobook is reading, although each can be a worthy endeavor.)

It’s curious to learn which celebrity authors looked for the nearest amanuensis. Despite being a single mother pinioned by children in the mid-1990s, Mia Farrow wrote 1997’s starkly lovely What Falls Away: A Memoir, whereas Marianne Faithfull enlisted rock journalist David Dalton to assemble 1994’s Faithfull, even though she is well read and considered a Serious Enough Artist to have taught at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. (It’s a real school. Look it up.)

That Faithfull’s memoir was well received (as it should have been: as I’ve mentioned in the recent past, it was dishy but soulful) couldn’t have escaped the notice of her one-time partner in crime Keith Richards, who can be fairly held accountable for the musician memoir boom following the galactic success off his deservedly lauded 2010 memoir, Life. He can be forgiven for going the as-told-to route because what the journalist James Fox pieced together from Keith’s recollections is so tirelessly absorbing; the book retains a raconteur’s easy-flowing humor and the hint of English gentlemanliness underneath its overarching “Fuck off!” spirit.

The most interesting thing about Keith’s book’s success is how unremarkable his actual story is: while his has been a life of extraordinary achievement, it can’t be said that he had to tunnel through a mountain of seemingly insurmountable obstacles to get there. (Most of the adversity he experienced he brought on himself.) Life isn’t Coal Miner’s Daughter; Life is David Niven’s The Moon’s a Balloon with heroin.

Do you know what’s a far more cynical publishing trend than the too-often value-free celebrity memoir? The celebrity-authored (or “-authored”) children’s book. Some celebs do actually bother to write a story intended for children, but the hot new plague is the cross-merchandizing of song lyrics: the publisher takes the words to a living or dead musician’s classic tune for grown-ups, sprays them across the length of a kids’ picture book, hires someone to illustrate them, and calls it an extremely lazy day. Artistically, this gambit pretty much never works: even if they do rhyme, lyrics recited by a reader unfamiliar with the song don’t scan, and a chorus’s seemingly pointless repetition on the page is dizzy-making.

But economically, these books can be winners: adults tend to buy what they like for their kids. It should be noted here that Keith got aboard the kiddie lit train with 2014’s Gus and Me: The Story of My Granddad and My First Guitar. When I saw that book, I pictured an editor at a desk: “Life was a smash. We need a follow-up. Let’s ask Keith if he has anything left.” Baby, he was bound to run out of ideas. Now fuck off.

Nell Beram is the coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic staff editor.