Faces of Death

A curious collection of famous death masks, from Audubon to Whitman

Before we learned to stave off death with antibiotics and pollution control, death was as much a part of life as living. People died of plague and chest colds, childbirth and drinking cold water; and when they died, they did it at home. From the late eighteenth century until the advent of photography, the dead were commemorated through casts of faces, or death masks: portraits in plaster, rendered quickly on a person’s deathbed. A death mask freeze-framed someone as they were in life, with the knowledge that their faces could capture something essential, and could speak for the living without language. (This was considered common, not creepy.) The world’s largest known collection of these plaster casts is located in the Firestone Library of Princeton University, on the north side of campus.

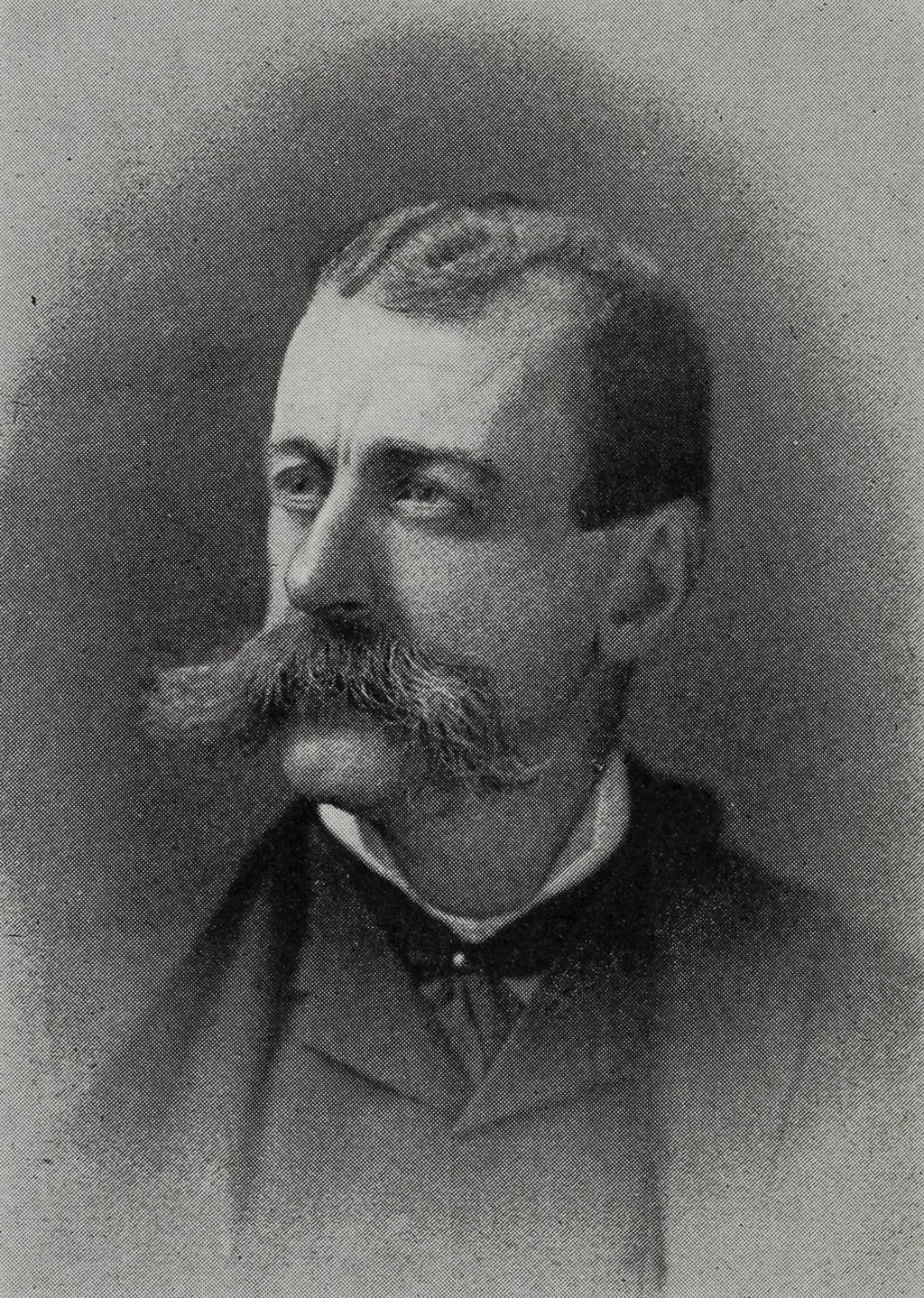

A summer afternoon in the middle 1860s, Laurence Hutton, the dramatic critic for the New York Evening Mail and later the literary editor of Harper’s, ducked into a small bookstore in New York City and noticed a boy attempting to sell a plaster cast of a face. The face struck Hutton as familiar; it was tarnished with age, he wrote in his memoir, but it was unmistakably the visage of Benjamin Franklin. Curious, he gave the boy a few shillings to lead him to where he found the face. The boy led him down Second Street and across the Marble Cemetery, where, waiting in the adjacent alley, was a pile of ash barrels containing masks of other familiar faces, including Oliver Cromwell and George Washington. All told, there were enough masks to fill a wagon, which he did. Hutton unloaded his treasure trove back to his house in the city, where his father, a former student of physiognomy, told him exactly what it was he had discovered.

After realizing the value of his hoard, Hutton returned to the alley full of remorse, but not enough to consider returning his trove. Mostly, he wanted to figure out whose collection he’d stolen. After knocking on most of the doors in the neighborhood, he learned that the previous owner of the casts was an assistant to the phrenologist George Combe. Upon Combe’s death in 1858, Combe’s wife ordered the removal of the “nasty, ghastly things,” and years later disposed of them in the alley. Conscience cleared, Hutton apprenticed himself to the study of death.

Hutton was well known as a collector. He stockpiled friendships as well as diaries, address books, and autographed copies of books from his famous friends like Walt Whitman, William Archer and Mark Twain. “Probably no man alive today has as many [friends] among American and English creators of things beautiful,” an article in the Princeton Alumni Weekly noted. (Hutton received his masters from Princeton in 1897 and later became a resident of the town). On his search for death masks, Hutton culled stories of the living and dead, journeying through alleyways and courthouses, through country roads and strange, dusty basements, all across the United States and on to Berlin and Paris and the Isle of Shoals, sneaking into crypts to make his own plaster casts. During this time, he mostly read obituaries.

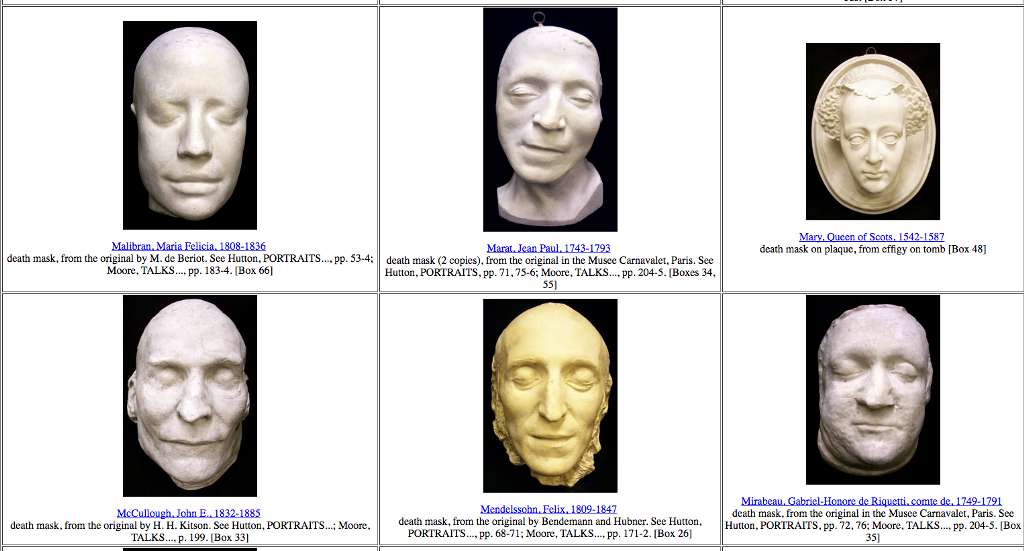

Hutton distilled his collection into the Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks, comprised of original masks and copied casts from the originals, which he donated to Princeton University. He wrote two books on his collections, Portraits in Plaster and Talks in a Library With Laurence Hutton about the men (and occasionally woman) whose life and death masks he collected. (Elizabeth I. of England, Queen Louise, Mary, Queen of Scots, and a cast of Italian actress Eleonora Duse’ right hand comprise the death masks of women on display at Princeton). The stories center less around the legacies of these individuals, and more on how Hutton came to procure their death masks. Even so, reading the stories provides less insight into the collection than to Hutton himself. He is sometimes scientific (“Calhoun’s cranium is entirely different in shape”), sometimes extremely dry (“Their faces were smooth and shaven, but they were both far from being bald”), but often his scholastic rigor and appreciation for weird details suffuse his anecdotes with breezy wit.

Hutton’s writing suggests death masks access a universal truth about a person. This concept is reflected in the (dated, racist) science of phrenology, the brain science of divination, which supposedly allows masters of the craft to infer a person’s character through their skull shape. The truth of a person could be identified through their language and legacy, yes, but more by their face. Hutton returned to this idea a few times, telling the story of a man who looked at a famous poet’s death mask and told Hutton everything there was to know about Samuel Taylor Coleridge without ever reading his poems. “All casts tell truth,” Hutton wrote. “They must tell truth. They cannot help it.”

The Laurence Hutton Collection of Life and Death Masks sits three floors below Princeton University’s Firestone Library, entombed in a vault. The vault itself houses all of Princeton’s collections, from megalethoscopes to art prints, altogether the size of three football fields. It’s locked to those without special clearance, and requires a multiple keys and an iris scan to enter. The vault contains about one hundred faces, from Leo Tolstoy to Queen Elizabeth, staring up through their plaster irises, through their boxes, through the walls, and through the thousands of feet of people scrolling through Twitter instead of studying. They look like something like supine, less-precise busts.

Julie Mellby, the Graphic Arts librarian of Princeton University, moves with the care expected of someone who has made a career of handling delicate, breakable things. The plaster masks are extremely heavy and fragile, and since visitors aren’t allowed in the vault, she has to haul them up one by one. The largest ones, some made incorrectly with cement instead of plaster, take two or three people to lift. Before Firestone library existed, the death masks were displayed the in another building called East Pyne, where they were on permanent view for about twenty years. Not a week goes by that Ms. Mellby doesn’t get a call about the death masks, thanks to their modest fame in the world outside the university. Academics and tourists often call to request to visit the death mask collection, or arrange a visit with one mask in particular. These visits are bolstered less by morbidity, Mellby thinks, and more by genuine, scholastic curiosity. “It’s people’s faces,” she said. “It grabs your attention no matter what you’re studying.”

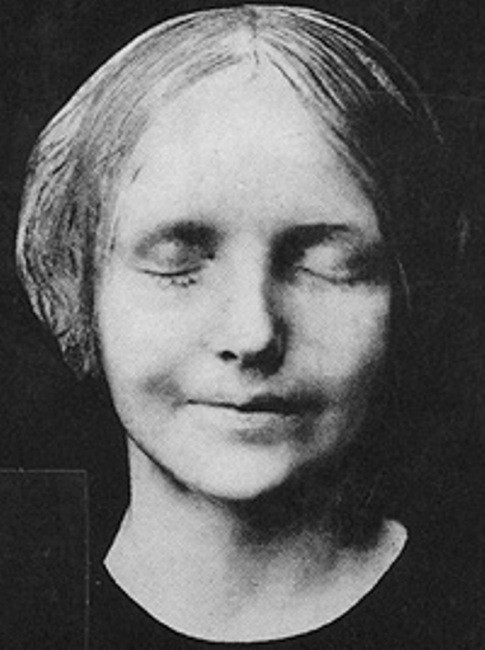

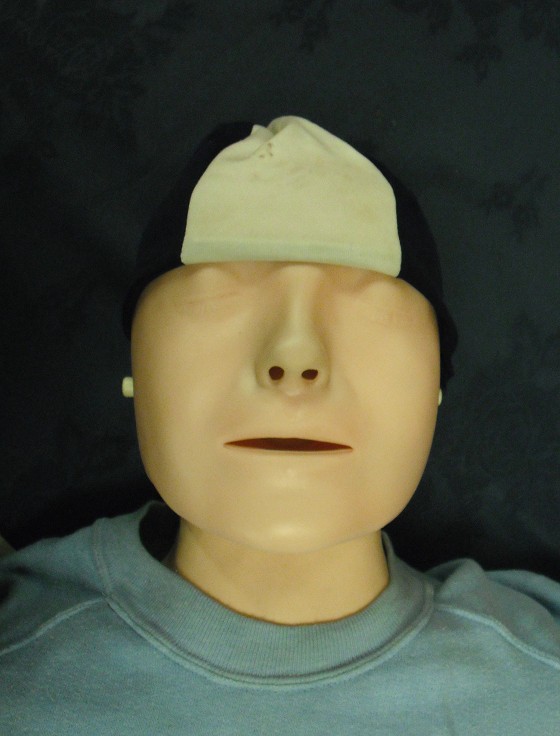

In nineteenth-century Paris, a lovely, tragic woman flung herself into the Seine. Her drowned countenance was so beautiful it was captured in a death mask known as “L’inconnue de la Seine,” forgotten only to resurface during the creation of the dummy used in CPR training. The androgynous, featureless dummy named “Resusci Anne” shares her face. Anne-Marie Tussaud, a French sculptor apprenticed to a physician, was forced to make death masks of murdered aristocrats during the French Revolution, including Marat, Robespierre, and Louis XVI. She later founded a wax museum in London, which spawned a few sequels. Yet Laurence Hutton’s collection is still the most famous and most complete of its kind, and bides its time in the basement of the library, a mausoleum of stories, which seems fitting.

We tell two sorts of stories about these death masks: the stories about the lives of those who are now frozen in plaster, and the stories of how those masks were acquired (which is of course a story about the collector). Stories are the currency of the living, even when the living is done. In life and in death, Laurence Hutton collected people — their bodies as well as their stories. Where Hutton’s own writings mention death, the tone is rarely sentimental, a quality he credits to overexposure. “I had lived so long in intimate intercourse with these things (…) that I had learned to look upon them with something like a hardened insensibility as to their actual significance,” he wrote in Talks. “But when it comes to the contemplation and examination of the dead faces of the men you have known and loved in the flesh it was a very different matter.”

The death mask is neither beautiful nor is it art; it’s the story of how a person came to wear the face they died in. Whether we would have learned more about Hutton from his own death mask is an impossible question, because he does not have one. (He had tried to make a life mask, an effort that proved unsuccessful. “I was willing to sacrifice my moustache for the cause of science,” he wrote, but it was impossible to salvage the mask after it snagged on his face. The mask was removed and broken gently with a hammer, which was not at all gently, and crumbled with a tap.) So we are left with his life, his words, and one hundred plaster faces, hidden behind lock and key.

Rachel Stone is the Editor-in-Chief of the Nassau Weekly. Her writing has appeared on The Toast, The Hairpin, The Awl and Narratively. She was once an Awl Summer Reporter.