What Should The Olympics Sound Like?

A brief history of the Olympic song

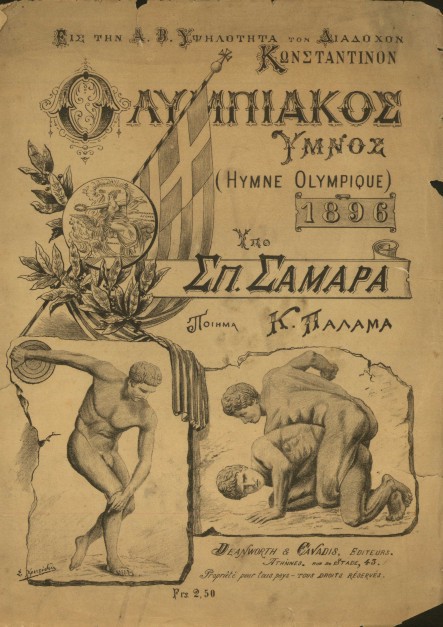

For well over a century, Olympic songs have been less the progeny of lyricists than of a handful of staple concepts. In 1896, the Greek poet Kostis Palamas inked into history a series of keywords that no Olympic songwriter since has been able to shake. His lyrics to composer Spyridon Samaras’s “Olympic Hymn,” which debuted at the opening ceremony to the first modern Olympiad in Athens, read like an itemized list of epic ideas: perseverance, strength, victory, beauty, and — not unrelatedly — a large body of water. “Ancient immortal Spirit” (Αρχαίο Πνεύμα αθάνατο) is the opening line of Palamas’s hymn. Twelve decades later, Katy Perry summoned that same image. “When you think the final nail is in; think again / Don’t be surprised, I will rise,” she sings in “Rise,” this year’s official Olympic song. The words picture her rising from the near-dead; the music video shows her parachute running, as if showcasing her skills at the NFL Scouting Combine.

In his latest prodigious book, The Games: A Global History of the Olympics, David Goldblatt marks 1984 as a turning point in Olympic music. Out with the Victorian loyalty to classical orchestral arrangements, in with marketable pop stars, preferably from the host country. “The combination of blockbuster movie and stadium mega-concert has often proved a bizarre medium through which to tell history,” he quips. “And that, for all the Olympian flummery, is what states and Olympic organizers have been paying up for.” Pop songs are indeed curious receptacles for history. But their shared compromised position is what connects Céline Dion to the fin-de-siècle Czech composer Josef Suk, pop stars to orchestral acts, a money-making juggernaut to a quaint quadrennial tradition. The pop songs have been surprisingly faithful to the motifs of the orchestral tradition. Just take the case of the composer Richard Strauss and Gloria Estefan.

In 1933, Strauss was approached by the Nazi regime to compose the song for the upcoming Games in Berlin in 1936. He walked a fine line between disinterested acquiescence and active ingratiation with the regime. As David Clay Large tells the story in his book Nazi Games: The Olympics of 1936, Strauss wrote to the Jewish writer Stefan Zweig, saying, “I’m killing time during the slack Advent season by composing an Olympic hymn for the proletarians.” Shortly thereafter, he seemed to have gotten over his contempt for his own project. Strauss asked for a private performance to preview the piece for Hitler. Echoing his Greek predecessors, he called his song “Olympische Hymne” and set the dramatic composition to the poet Robert Lubahn’s lyrics, which called for Kraft und Geist (“strength and spirit”) and athletic Herz (“heart”).

Sixty years later, Gloria Estefan put a jubilant spin on Strauss’s monumental tone at the 1996 Games in Atlanta with her song, “Reach.” Thematically, she hewed close to “Olympische Hymne,” ambitiously invoking the future (“I’m gonna be stronger”), the conditional (“I’d put my spirit to the test/ if I could reach”), and the purely hypothetical (“Those dreams you want with all of your heart”). If what made one of her best songs, “Rhythm Is Gonna Get You,” was its “tribal, on-the-loose and non-negotiably infectious” beat, as Wesley Morris put it, what unmakes one of her worst, “Reach,” are its chronologically challenged and corporately calculated lyrics. But who’s to say that Estefan’s song was more calculated than Strauss’s?

Most Olympic songs — even the early ones — have little to do with the Games, much to do with star power, and all to do with the disastrous attempt to calculate inspiration. Even Palamas and Samaras couldn’t escape the temptation to make tone-deaf demands to the athletes. “Give life and animation to these noble games!” exclaim a chorus of voices halfway through the “Olympic Hymn.” Olympic songs are not unlike the motivational posters you find in a Duty Free In-flight Shopping catalog — “Teamwork: Be strong enough to stand alone, be yourself enough to stand apart, but be wise enough to stand together when the time comes.” They want so desperately to telegraph motivation through song.

Whitney Houston is no exception. Taking the baton from her forerunners in her classic “One Moment in Time,” from the 1988 Games in Seoul, she pleads, “I want one moment in time / …when the answers are all up to me.” Reputable sources have put Houston’s at the summit of great Olympic songs. “‘One Moment in Time’ became the temporary new National Anthem,” Fuse gushed. For USA Today, it “perfectly encapsulates the spirit of the Games.” “It’s often replicated… but never duplicated” was how Bustle put it. Albert Hammond, Houston’s songwriter, didn’t mince words. “The best Olympic song for me — and not just because I wrote it — is ‘One Moment In Time,’” he told the British music magazine NME in the lead-up to the 2012 Games in London. “It’s an anthem. I can’t even remember the others.” But maybe Billboard unwittingly hit the nail on the head when they praised its “classic Olympic lyrics.” Strength, spirit, and heart, indeed:

I broke my heart

Fought every gain

To taste the sweet

I face the pain

I rise and fall

Yet through it all

This much remains

Large bodies of water appear in Olympic songs every once in a while. Montserrat Caballé and Freddie Mercury gave the Mediterranean a rhapsodic ode in “Barcelona,” the anthem for the ’92 Games: “Por ti seré gaviota de tu bella mar” (“For you, I’ll be the seagull to your beautiful sea”). Three Olympics later, Björk anthropomorphized the ocean in “Oceania,” the official song of the 2004 Games in Athens. “Oceania,” though, came four years too late — Athens isn’t near any ocean; it would have been a better fit for Sydney in 2000, when Björk’s ’90s luster hadn’t yet faded. In sum, it was a spectacular trainwreck.

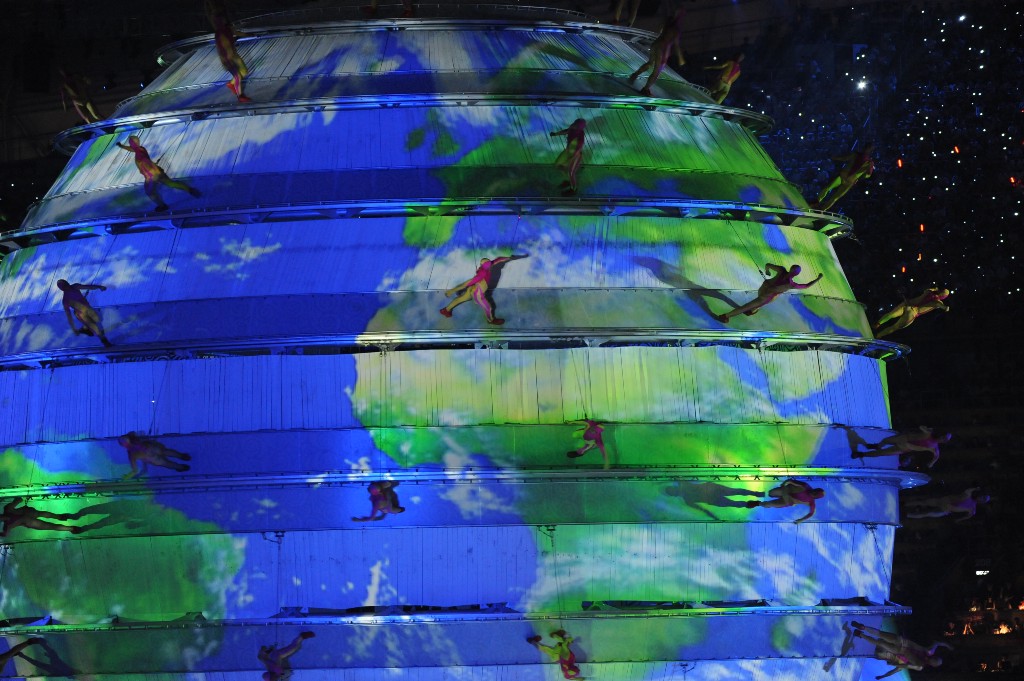

“The song is all about how the ocean doesn’t see boundaries between countries and thinks everyone is the same,” Björk told the Independent. This wasn’t entirely evident halfway through the song during the opening ceremony. NBC’s Mary Carillo noticed during the broadcast that “Oceania” required color commentary and took it upon herself to provide it. She treated the performance as an Ikea chair to be assembled, guiding the audience through each step with the tone of an instruction manual. “The lyrics that Björk is singing are as if sung by the sea itself,” she said. “That’s why the sea image is on the big screen.” Carillo’s trademark deadpan didn’t do Björk any favors.

If Houston’s was, by consensus, the best, Mercury and Caballé’s “Barcelona” was the most memorable. “Barcelona” is to the ’92 Olympics what Randy Newman’s “I Love L.A.” is to Los Angeles sporting events, and it’s just as subject to revisionist history and appropriation. “Barcelona” wasn’t actually written for the Games; it was written as a one-off single. Mercury wanted to sing opera, Caballé, pop. But the song itself left too much on the cutting room floor, on both sides. Mercury’s voice couldn’t overcome the song’s tempered pace, yet that pace didn’t allow Caballé’s operatic vowels to fully bloom either. And, to make matters worse, their voices didn’t ever convincingly harmonize. “Barcelona” is a collage whose pattern is so obvious that it defeats the purpose, whose parts are so perfectly cut that they clash. As Time summarized it, “Where does this rank among Freddie Mercury songs? Going to go ahead and say in the lower 50%. Where does this rank among Olympic theme songs? Easily upper 10%.”

There’s one universal quality to Olympic songs: the lyrics are always laughably bad. The best that Muse could come up with, in their anthem to the 2012 Olympics in London, was five minutes of, “Race / It’s a race / But I’m gonna win / Yes, I’m gonna win.” Not exactly what one would expect from a band that claims George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four as a major inspiration. Where does this all leave us? Why are the lyrics to Olympic songs so terrible when the singers mostly aren’t? Does it all just boil down to the fact that none of them — or their lyricists — have ever competed athletically at a high level?

Maybe the better question is: What kind of songs should we have instead? Of all the major sporting events (whose corruption is on par with the IOC) the FIFA World Cup has the best formula. In recent tournaments, it’s relied on one famous mainstay, Shakira, and surrounded her with a rotating cast of characters, presumably representing local-ish color — K’Naan’s “Wavin’ Flag,” Coca-Cola’s official anthem for the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, is a good example. An added benefit of the World Cup’s handling of music is that, even if you happen to notice what the official songs are and you don’t like them, you’re not forced to listen to them often.

If the major problem with Olympic songs are their nauseating lyrics, then the Olympics should embrace genres of music that don’t care about them. Yes, exactly. I’m talking about worldbeat and new-age music. You know, “Adiemus,” the orchestral masterpiece put to fake Latin. Or Enigma’s “Return to Innocence,” whose chorus you think, instinctively, is Native American until you google it and realize that it’s sampled from a drinking song of Taiwanese aboriginal peoples. Someone might think that associating with new-age gibberish would be a non-starter for the International Olympic Committee. That someone would be wrong.

Worldbeat and new-age — I’m still not convinced there’s much of a difference — have the added benefit of making you feel like you’re at an ideal U.N. summit. (The often exotic or grandiose location of the Games helps.) A chorus of children booms West African-sounding lyrics in the background while vocalists in the foreground give Latin sounding syllables a pop inflection. It’s weirdly inspirational and uplifting, in that liberal guilt kind of way. Certainly it’s more inspirational than any of the Olympic songs that have graced the stage of an opening or closing ceremony in the last thirty years. Most importantly for the IOC, these songs will do a much better job than a famous pop star of inuring audiences to widespread corruption, the pillaging of the host city, and the inevitable steroid-plagued controversies. Go ahead. You try and get mad at the IOC while fifty children are singing, “A-na-ma-na coo-le ra-we / a-na-ma-na coo-le ra / a-na-ma-na coo-le ra-we a-ka-la.”

Bécquer Seguín teaches at Lawrence University. He writes regularly for The Nation and other magazines.