The House Where You Live Forever

The Reversible Destiny of Madeline Gins

This story was co-published with Longreads.

On a bright afternoon in October 2013, Madeline Gins walked into the office of her architecture practice, in an unrestored loft building on the edge of SoHo, slightly out of breath. Before she arrived, the space—a large open room occupying the fourth floor of the building—had been so still that it was almost possible to forget about the two architects staring into computer screens near the back windows. Gins entered, and the atmosphere began to buzz.

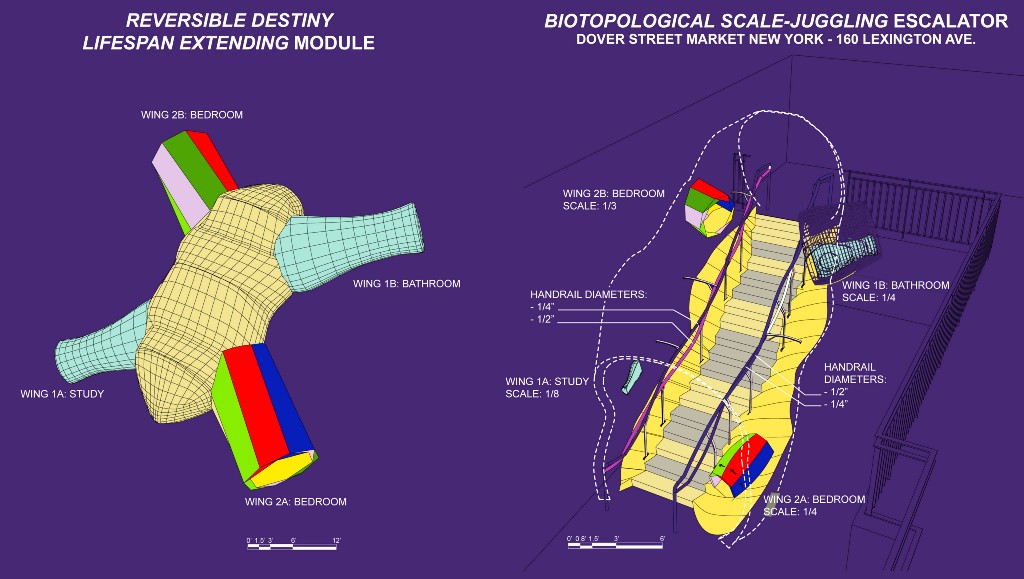

“Is Joke here?” she called out, referring to her project manager — a Dutch architect named Johanna Post — by her nickname (pronounced yo-ka). Post had stepped out, but another colleague informed Gins that she would return before their next meeting. Gins exhaled and nodded. She and the small staff of architects who work in her office, called the Reversible Destiny Foundation, had been in a state of heightened urgency for months. They were rushing to complete a new project, commissioned by the high-fashion store Dover Street Market, which would soon open a location in a Beaux-Arts building in Manhattan’s East 30s. The facade would remain unchanged, but the interior would become a mish-mash, combining the work of a number of different artists and architects. Gins would build a large covered stairway connecting the building’s open-plan third floor to the mezzanine above. But Dover Street had given Gins far less space to work with than she initially thought she would have; her team was scrambling to make sure the project would both live up to her standards and be able to fit.

Assured that preparations for the meeting were under control, Gins walked over to a large table near the front of the room, stacked high with books and papers. In the center, a heavy glass orb sat on top of a slender vase; next to it was a fish tank filled with neon bouncy balls. The wall nearby was plastered with renderings of a project called the Reversible Destiny Healing Fun House. From a distance, it looked like a cluster of spheres and tubes, painted in red, pink, yellow, and blue. The interior view showed that these structures were hollowed out, and that together they formed the walls of the building, surrounding a big open room filled with mountainous, rammed-earth terrain. “Here, feel this,” Gins said as she sat down at the table, tossing me a piece of fluffy yellow stuff. “It’s natural sponge.” It had been a couple weeks since I’d first met Gins, and I asked her how she’d been. “Ummm.” She thought for a moment. “I’ve been everything.”

Gins, in her early seventies, gave the impression of a child trying to impersonate her grandmother: her blonde hair was fastened in pigtails, and her small frame was draped in too-big clothes in shades of deep red. Her face was clear-eyed and rosy, even as wrinkles rippled across her cheeks. She exhaled again. “You know, I have huge responsibilities,” she continued. “Pressing ones.” Most architects generally want to design comfortable, visually interesting buildings for their clients. Gins found that aspiration boring. Instead, her goal was to build spaces that would keep people from dying.

According to Gins’s elaborate theory of Reversible Destiny, developed over the course of a forty-five-year collaboration with her husband and artistic partner, Shusaku Arakawa, death may not in fact be inevitable. People are lulled into believing it is because they focus only on what has come before — the “thus-far obligatory downhill course of life,” according to Gins. Their brightly colored, disorienting dreamworlds, which look more like surrealist playgrounds than traditional buildings, are intended to jolt people out of their normal routines and force them to move through life differently. If people are unable to fall back on their physical and mental habits, Gins and Arakawa said, they will be open to new ideas, including the possibility that they can lengthen their lives and, eventually, resist death entirely.

Her goal was to build spaces that would keep people from dying.

Avant-garde architecture is expensive, though, and many of Gins and Arakawa’s ideas, including the Healing Fun House, remain on paper. Prior to the Dover Street commission, only one Reversible Destiny project — a private home in East Hampton, New York — had been built in the US. (Several have been constructed in Japan, however, including a number of wonky apartments that house short- and long-term tenants.) Dover Street Market provided a chance to bring Gins’s work to many people who otherwise wouldn’t encounter it. But the store was scheduled to open in December, and Gins’s structure was not finalized. She insisted she was finding the rush creatively invigorating. “I think the universe might be against Reversible Destiny for a little while longer, but it’s changing,” she said.

That December, before the project was scheduled to open, I began to have problems reaching Gins. She postponed meetings, saying she hadn’t been sleeping. She would reschedule them, she promised — always in a couple days, when, she said, she would be feeling better. For a few weeks, the only way to communicate with her was over the phone. I eventually learned from a friend of Gins’s that in the early aughts, she had been diagnosed with breast cancer. The disease had long been under control, but Gins’s health had recently taken a turn. She had been determined to use the Dover Street commission to push the boundaries of Reversible Destiny, conducting new research that she thought might help keep her alive.

Throughout early January, I continued to try to contact Gins, now with no response at all. One bright, freezing afternoon, while crossing the Manhattan Bridge, an email arrived. Inside was a notice of Madeline Gins’s death, that morning, from metastatic cancer.

I met Gins for the first time in September of 2013, on the thirty-second floor of a high-rise just south of Columbus Circle. She had recently moved in, and her apartment was still mostly empty. The only furniture in the large living room was a pair of brown, donut-shaped objects whose purpose wasn’t immediately clear. One corner of the space was painted deep purple, with a purple rug, four purple chairs, and a dining table covered in purple placemats. I sat in one of the purple chairs until I felt that someone might be looking at me. I turned and saw Gins standing there; she may have been behind me for some time. “I like practical jokes,” she said, sitting down. “But only certain types of practical jokes. Extended ones.”

In early 2013, Gins’s cancer had begun to worsen significantly. Her doctor advised chemotherapy, and after a few months of uncertainty, she agreed to the treatment. But in early July, after receiving a dose of chemo, she became acutely ill and had to be rushed to the hospital. She was admitted, near death. For a week, she floated in and out of strange, vivid dreams, which she believed were giving her instructions that she could use to save her life. When she awoke, she felt as though she’d been told, “You don’t have too much time. You’ve got to get cracking.”

She threw herself into her work as soon as she was out of the hospital. She moved to a rehabilitation center and asked Post to visit every day so she could get up to speed on the Dover Street Market project. She also went back to a book manuscript, which she had been writing for five years and wanted badly to finish. In her dreams, she felt like “a sheet was pulled back, and the answers came” to a number of questions she’d been asking about how to move forward with Reversible Destiny.

Gins and Arakawa’s work generally focused on destabilizing people physically and mentally. In the early days of their collaboration, they drew up a list of desirable states of being, like tentativeness or the loosening of identity, that they believed would encourage people to be more open to the unexpected. They called these states “procedures.” Every element of their buildings, from the materials used to how people would be able to move between rooms, was designed to help people access different procedures and, as a result, find new ways of moving and thinking. They added to the list of procedures frequently, whenever they found a gap in their thought process. Procedural architecture, as they called their technique, was a way of creating buildings that had far more in common with poetry, in which the writer experiments with language to achieve certain effects, than with most traditional architectural practice.

Gins and Arakawa’s work generally focused on destabilizing people physically and mentally.

Their work plays with consciousness: how do people understand the relationship between their bodies and their surroundings? And how can that relationship be reimagined? Before her illness, Gins started to wonder whether there were different types of consciousness to take into account. What about consciousness at the cellular level, or at the level of the entire population? Might those types of awareness affect a person’s ability to live forever? The need to target different “scales of action,” as Gins called them, was reinforced in her dreams. She knew that it might be perceived as a bit out there: “it seems very radical, even to a radical,” she said. But still, she didn’t want to waste any time trying to incorporate these ideas into the Dover Street commission. “Our architecture is polite to the human body,” she said, “but it should also be polite to, say, neurons.”

Gins figured she needed to develop a procedure that would help people recognize how many different scales of action there were in their bodies and in the world around them, and to practice paying attention to all scales simultaneously. She planned to test the new procedure by using many different scales in the Dover Street staircase: railings of varying thicknesses, and a stairway lined with models of Reversible Destiny rooms, each built to a different scale. (A plan for each of the seventeen steps to be a different height had to be abandoned for contravening the building code.)

The afternoon I visited her in her new apartment, Gins received the most recent renderings of the stairway. The steps would be concealed beneath a large, tunnel-like covering, allowing the structure to feel cut off from the rest of the store; a small space where reality could be manipulated. Gins compared several options for the shape of the stairway’s covering. She was unhappy with the curve of the walls; she wanted the sides of the structure to be less symmetrical. But she was unable to modify renderings of the design herself. Neither she nor Arakawa had any formal architecture training; instead, they worked with a team of architects who were responsible for translating their abstract ideas into concrete reality.

Gins studied the renderings, trying to get a sense of how each shape would impact the perception of a person walking down the stairs — not easy, when looking at a three-dimensional image printed on a flat piece of paper. She asked her assistant for his opinion, and then me for mine. In the past, she would have discussed the options with Arakawa, going back and forth until they settled on a way forward. But in 2010, Arakawa died of ALS. The couple had kept his illness secret from nearly everyone in their lives. Gins was devastated. She continued with their work, but she felt the loss of her collaborator acutely. In their partnership, Arakawa had been the decisive one. Gins was digressive; she was interested in evaluating every possibility in front of her, even the most outlandish. If she could choose everything, she would.

A black plastic bag rushed upward through the air outside the window, catching Gins’s attention. “Oh, hi, hello! Thanks for showing us the wind,” she exclaimed. With a large, bony hand, she placed the pages off to the side of the table, deferring the decision.

Gins was born in 1941, in the “Trotsky Bronx,” to immigrant parents active in the Communist party. When she was ten, her family moved to Long Island. As her parents became increasingly disillusioned with Stalin’s brutal leadership, they distanced themselves from Communist circles, though they held on to leftist politics. Gins remembers the “puffy-cheeked, square” Long Island suburbs as a place of oppressive uniformity in the nineteen fifties, but at the dinner table, her father had an unwritten rule: no story could be told the same way twice. If you were going to repeat yourself, you had to make it new. By the time Gins entered high school, she was reading Dylan Thomas and Samuel Beckett, and she befriended all the other girls who wanted to talk about poetry.

Gins studied physics and Eastern philosophy at Barnard. She started reading Zen and wrote poetry seriously. When she graduated, she was offered a Woodrow Wilson fellowship to pursue a PhD. “Keep it!” she said she told the committee, and decided to study painting at the Brooklyn Museum Art School instead. There, she met Arakawa. Though he had been exhibiting painting and sculpture in Japan since the late ’50s, he enrolled at the Brooklyn Museum school upon moving to New York, in order to secure a visa. Arakawa grew up in Nagoya, and was eight years old when, during the long wind-down of World War II, the city was repeatedly firebombed. Some of his first major pieces were a series of large coffins; inside the boxes, atop shiny peach and purple satin, lie crude chunks of mangled concrete.

Gins and Arakawa were inseparable as soon as they met. It was the early sixties; American political and cultural life seemed to be rapidly unraveling. Gins and many of her friends were in distress about the inevitability of death, the emptiness of life, the nuclear threat. “I think I was nearly suicidal, but I was a coward,” Gins told me. She would have long arguments with her father. “I’m saying to him, ‘We’re all going to die, I can’t believe we’re all going to die.’ My father is, ‘Shut up, I don’t want to hear it.’ He wanted to always protect everyone, and I looked at him and said, what a fool. Nobody can protect anyone.”

Gins saw that Arakawa, too, seemed on the edge of a breakdown, unable to live with the human condition. The two began to wonder if there wasn’t something they could do to combat the “sad, terrifying” reality they faced. If they couldn’t survive in the world as it was — harsh, futile, always moving toward death — they would have to construct a more optimistic version of it: a world in which dying might not be inevitable. In 1965, Gins and Arakawa went to City Hall and were married. They bought an old cheese-and-salami warehouse on Houston Street, moved in, and got to work trying to figure out how to make art that could rid the world of death.

In late October, in her studio on Houston Street, I asked Gins to explain to me how Reversible Destiny could keep me from dying. In previous conversations, she had skirted the specifics, instead going into long, looping digressions from architecture into philosophy or literature. Work on the Dover Street Market commission was behind schedule, and Gins seemed to have lost weight. But she was brimming with energy. Like a pastor surrounded by potential converts, she viewed any interaction as an opportunity to persuade someone of the necessity of Reversible Destiny. We sat at a large table near the front windows. Arakawa and Gins’s five-thousand-volume library stared down at us from shelves that lined one wall of the room. In describing her work, Gins rapidly pulled ideas from books of philosophy, literary theory, science, art history, disability studies, poetry, and surrealism. Her language, the critic Arthur Danto has written, is like “Einstein as adapted for Wittgenstein by Gertrude Stein.”

She viewed any interaction as an opportunity to persuade someone of the necessity of Reversible Destiny.

In a 2011 letter to Jasper Johns, Gins explained how, when she and Arakawa began working together, they started “cataloging systematically the underlying tendencies of thought and action of a person.” They wanted to understand clearly how people tend to think and act, so they could figure out how to push those boundaries. They were particularly interested in language, realizing that the words people use have the power to paralyze them, or to prevent them from thinking outside the status quo. Taking up a Wittgensteinian idea — “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world” — they hoped to develop a set of replacement terms for the everyday concepts that had become so overused that they were meaningless. “When we say ‘space,’ we have very little notion of what we’re talking about,” Gins explained. “You get spacey when you mention space. So we substituted ‘landing site.’” Later, they sought to reform standard patterns of movement and thought in the same way.

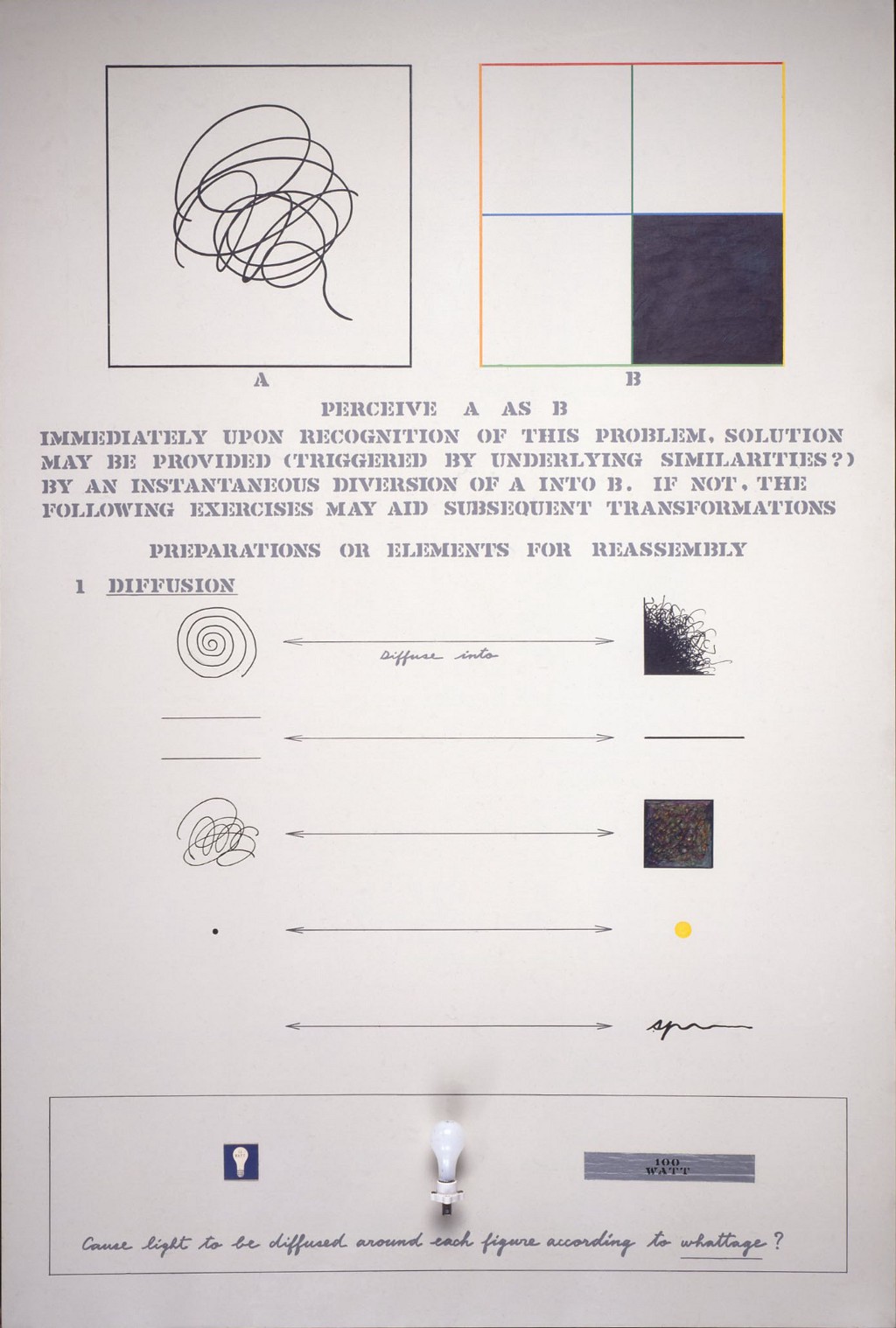

The pair’s first major collaboration,“The Mechanism of Meaning,” was an attempt to combine words and painting into a participatory project that would get people to do things they might consider difficult or impossible. They began in 1963 and added to the work over the course of the next decade. “Mechanism” consists of eighty-three panels, each eight feet tall and five-and-a-half feet across. The panels — mixed-media pieces that incorporate language, painting, collage, diagrams, and 3D objects — direct viewers in a series of thought experiments, exercises, and games that are meant to elicit the full range of their capabilities “right on the spot,” Gins explained. “So you could say, ‘Oh, I can do that, I’m doing it right now.’” Several of the panels were exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1970.

Four years later, the Times critic John Russell wrote, “Among current undertakings in art, none are more ambitious in scale than ‘The Mechanism of Meaning.’” In 1979, the couple published a book of reproductions and accompanying essays explaining, in a circular, at times impenetrable way, the concepts behind “The Mechanism of Meaning.” “Death is old fashioned,” they wrote. “Essentially, the human condition remains prehistoric as long as such a change from the Given, a distinction as fundamental as this, has not yet been firmly established.” A New York Times reviewer enjoyed the book but recommended it mainly to those readers possessing “a strongly developed taste for the preposterous.”

Although they were not yet creating architecture, Arakawa and Gins were leaning in that direction. Alan Prohm, an artist and academic who has collaborated with the couple, said that by making “huge paintings that are too big for the visual field,” the artists insisted “that a painting needs to be perceived with the whole body,” as one perceives a built environment. Still, they wanted to go further. If they were to dismantle the automatic way that people live and think, Gins and Arakawa realized, they should try to alter the actual spaces in which they spent their time. What would happen if people were constantly surrounded by the unpredictable?

What would happen if people were constantly surrounded by the unpredictable?

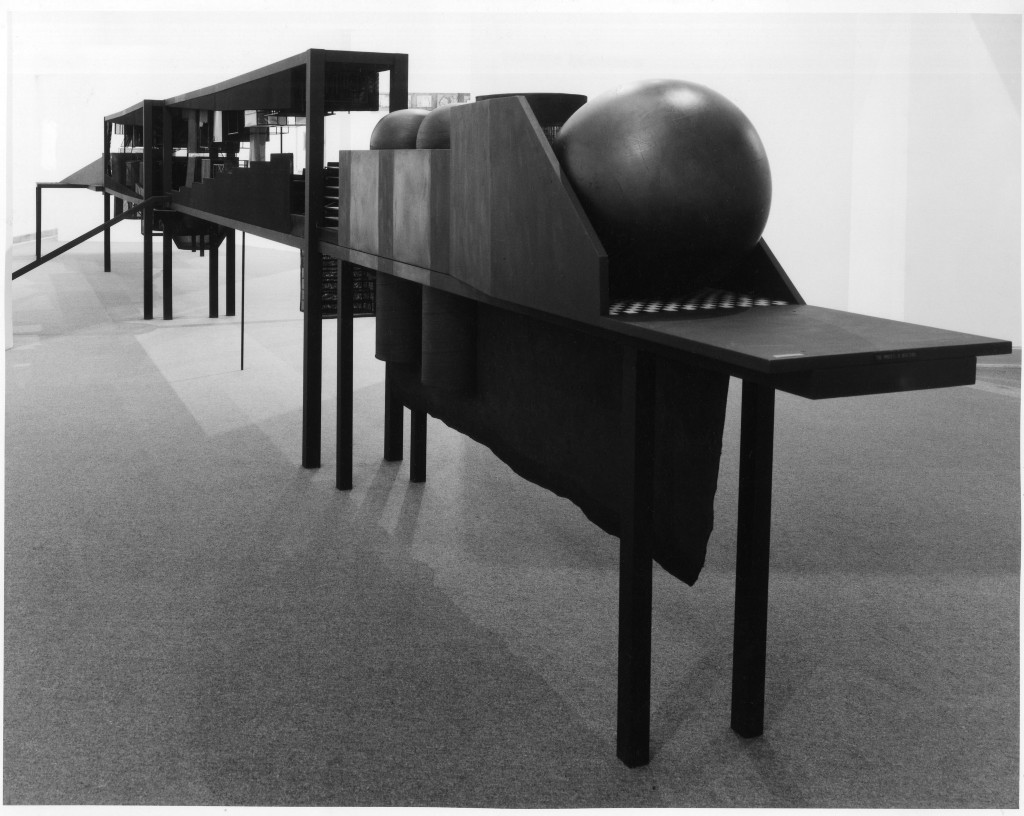

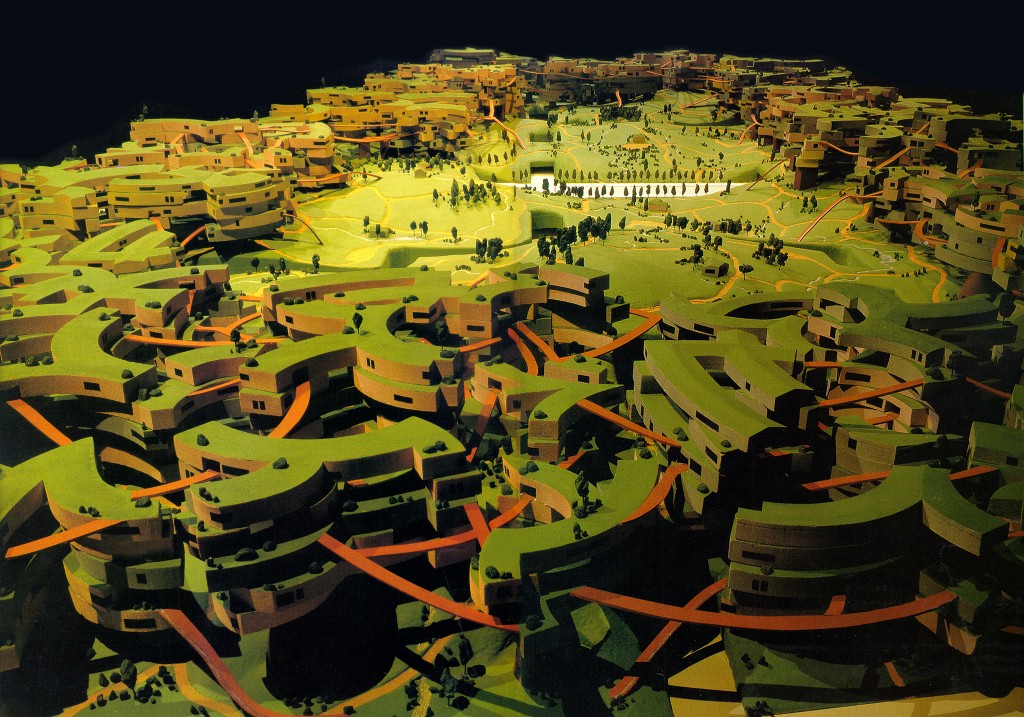

The rectangular houses in which many people spent their days reminded Arakawa and Gins of coffins. They envisioned a series of buildings that would take the perception-altering principles of “The Mechanism of Meaning” and scale them up dramatically. Neither knew the first thing about designing a building, and they didn’t have the money to pay for such a project. They established a charitable foundation that could fund larger-scale construction, and slowly, throughout the 1980s, they developed and revised ideas for a new piece. “The Process in Question/Bridge of Reversible Destiny” was finally shown in 1990 at the Ronald Feldman Gallery in SoHo. The piece was a forty-three foot-long structure made mostly of metal and wire mesh. Visitors were meant to walk across the bridge, which was littered with large objects that had to be climbed over or squeezed between.

In a text that accompanied the piece, Gins and Arakawa wrote that the structure was meant to be an “enterable basis of inquiry,” a space where someone could come in with one set of ideas and, by working through the challenges presented, leave with an entirely different understanding — with their destiny reversed. In the manner of much of the couple’s work, the bridge could be read as a whimsical joke: a reversed destiny was, as Arthur Danto noted in reviewing the exhibit for The Nation, “a great deal to ask” of a work of art. But underneath the humor was seriousness: Arakawa and Gins consulted with psychologists, biologists, and physicists in designing it. It was also their first collaboration with an architect. Danto wrote that the process of crossing the bridge was “unsettling and exhilarating.” The bridge convinced Arakawa and Gins that they wanted to commit to an architectural practice. They hired an architect, and began drawing up plans for “large-scale, utopian constructions.”

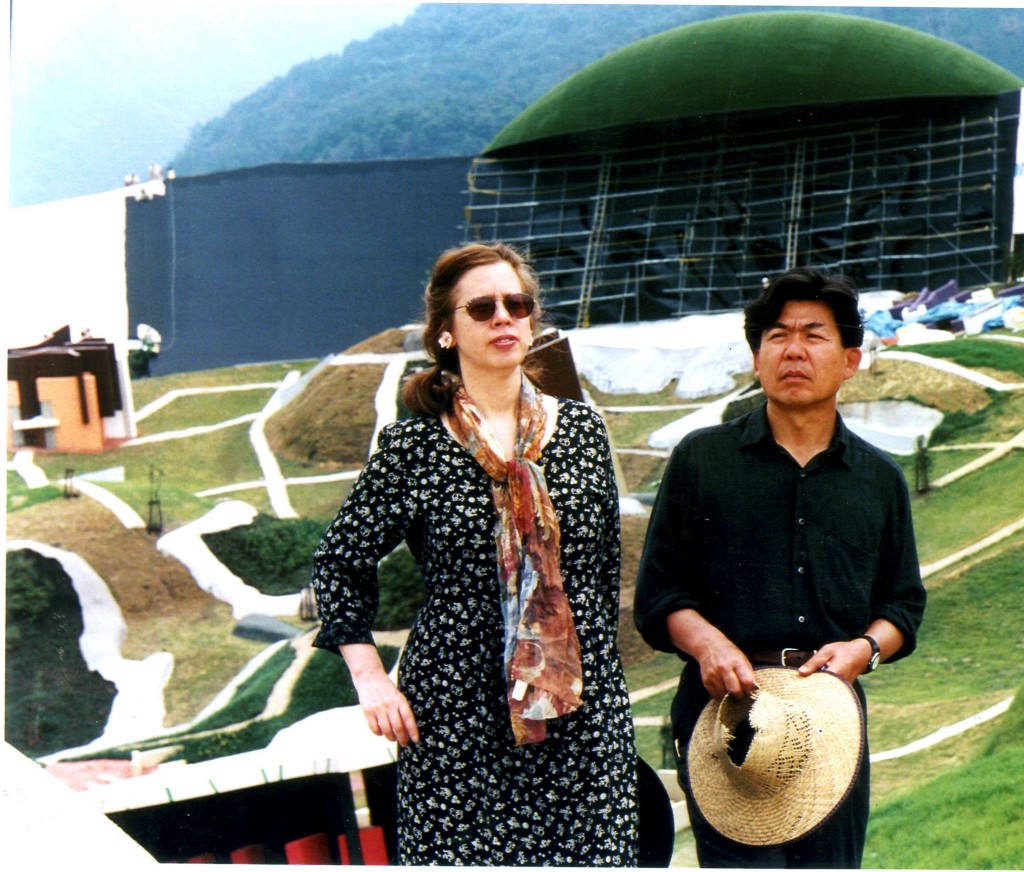

Their first commission, a “Site of Reversible Destiny” in a large park in Yoro, Japan, opened in 1995. They transformed the park into an obstacle course of sorts — a place of “purposeful experimentation,” Gins called it. Visitors navigate bridges leading nowhere, steep ridges, and deep holes. “Instead of being fearful of losing your balance,” Gins wrote in a visitors’ guide, “look forward to it (as a desirable re-ordering of the landing sites, formerly known as the senses).”

Throughout the ’90s, they hungered to build more, and faster. They designed apartment complexes, public housing projects, whole cities meant to keep their inhabitants from dying. Few were built. Many critics believed that was a good thing. In a 1997 review of a retrospective of the couple’s work at the Guggenheim SoHo, Roberta Smith rebuked Gins and Arakawa for failing to explain how their “fractured, convoluted buildings, which keep people in a state of constant disequilibrium and unbalance, would actually work on a day-to-day basis.” She concluded that “theoretical follies, one of the plagues of contemporary architecture, have their place, and it’s on paper.”

In 1998, Arakawa and Gins were the unlikely winners of a design competition put on by the city of Tokyo. The city did not commit to build the proposal, a $7 billion commercial and residential project in Tokyo Bay, and it quickly got bogged down by technical challenges. It wasn’t until 2005 that the couple finally built in Tokyo, on a much smaller scale: nine apartments in the city’s Mitaka district. Still, they considered it a huge success; they would be able to gauge how the principles of Reversible Destiny affected those living in their buildings consistently.

Convincing people to live in line with Reversible Destiny was rarely easy. Gins, who was responsible for communicating the ideas behind the couple’s work, had long conversations with friends, fellow artists, and potential clients, many of whom told her that what she and Arakawa were trying to do was obviously illogical. Of course, these conversations were at odds with the principles of the theory itself, which was meant to change thinking with confusion and provocation — productive dissonance. It wasn’t supposed to make sense. So Gins just aimed to keep people engaged. One friend, in particular, she had been working on for years. “Every time we meet she tells me how impossible it is,” Gins told me. “She said on the phone the other day, ‘No! Never going to happen.’ But she keeps wanting to talk.”

Gins became skilled at deflecting certain critiques. As my questions became more focused, she subtly steered the conversation back outward, toward her newest research or a more thorough explanation of some obscure element of her philosophy. It felt like swimming toward a marker that, just when you thought you might reach it, drifted a bit further away. “We want to become more knowledgeable,” Gins told me, toward the end of our conversation. “But most people don’t even try. They’re defeatists. They just wing it, they just go be human. But that’s not how we’re going to survive this life alive.”

“I still can’t prove it, so you know,” she added. “But to my satisfaction, I feel I can offer some protection now. Other people seem to agree. You’ll have to go to Bioscleave House, and see it for yourself.”

Bioscleave House (Lifespan Extending Villa) is a 2700 square-foot home in East Hampton that Gins and Arakawa completed in 2008. In the late ’90s, an acquaintance had commissioned the couple to build an extension onto her Hamptons A-frame cottage. In characteristic fashion, they made big, perhaps outsize plans, and the project became weighted down with budget concerns and delays. After eight years and $2 million, it was finally completed. They were elated, in part because it was the first architectural project they’d built in the US. But more importantly, they believed that Bioscleave House was the most complete manifestation of their ideas to date. Gins called it “an interactive laboratory of everyday life”; every element of the house was designed to help inhabitants see, even in their daily tasks, the opportunities to reimagine their existence. Because of this, Gins wrote, “whoever moves about within it wishing to live forever may do so.”

Every element of the house was designed to help inhabitants see, even in their daily tasks, the opportunities to reimagine their existence.

But, in late 2008, less than a year after Bioscleave House was finished, Gins and Arakawa learned that Bernie Madoff, with whom they’d invested an increasingly large portion of their money since the early nineties, had been arrested and charged with running a massive Ponzi scheme. The millions of dollars they had entrusted to him were gone. Arakawa decided to close their office, at that time called the Architectural Body Research Foundation, and laid off the entire staff except for Joke Post.

In the aftermath of the upheaval, Arakawa began to intermittently lose sensation in his arms. When Gins took him to a doctor, he was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s Disease, or ALS. “He was so strong and healthy,” Gins told me. “So I didn’t accept anyone’s diagnosis.” Arakawa didn’t accept it, either. He holed up on the second floor of their building, beneath the studio, and refused to see anyone but Gins, assuring her that in a few weeks, he’d be better. They told no one that he was sick. Gins isolated herself from her friends to care for him. She took Arakawa from one doctor to the next, trying find someone who would give them hope as his condition deteriorated. Eventually, he stopped leaving the house to go to the appointments.

In mid-May of 2010, Arakawa was rushed to the emergency room. He wasn’t breathing well, so he was admitted to the hospital and placed on a respirator. Gins asked that his room be filled with images of their work, so Post and another friend of the couple’s, Russell Hughes, brought in catalogues and hung posters on the walls. Hughes had a guitar, and he, Post, and Gins sat around Arakawa’s bed and sang Elvis songs to him.

Arakawa had been in the hospital for a week when Gins decided that he should be able to breathe without the respirator. It was a Monday morning, and she wanted to take him home. His doctor tried to dissuade her, but Gins wouldn’t listen. By the next morning, Arakawa had died. Immediately, Gins went back to their office, called in many former collaborators, and returned to work. “This mortality thing is bad news,” she told the New York Times, when she was interviewed for Arakawa’s obituary. “It’s immoral that people have to die.”

“She would say she was angry at the universe, angry at Arakawa,” Post said. “They had this idea, developed together, and this was not the plan. She just could not, could not accept the idea that he died.” In fact, Gins never accepted that Arakawa had ALS. “I think he died of toxicity,” she later told me. “You know, we lived in a loft building. There were funny things in the paint.” (Arakawa’s obituary notes that Gins “declined to give the cause of death.”)

Gins’s first project after Arakawa’s death was a commission from a Greek film director to build a healing center in the Peloponnese. It was arguably the most disorienting space she ever designed. The project, which Gins initially named “A Non-Tombstone for Arakawa,” was to be modelled on the Sanctuary of Asklepios, where ancient Greeks believed they could be healed of illness through sleep and dreaming. She later renamed it the Reversible Destiny Healing Fun House. In renderings, the Fun House is an amplified version of the couple’s aesthetic: the floors pitch and roll like ocean swells; in several places, the ceiling swoops down toward the floor dramatically. In order to create a feeling of destabilization, the building is split horizontally through its middle and the two halves are shifted out of alignment, each painted in a different color. The effect is of being unable to figure out where you are, or of being in two places at the same time.

But in the end, the Fun House was never built. The client died before construction could begin. “Dear (Hardly) Arakawa,” Gins wrote in a letter,

I will stay focused but I am all over the place.

A great communality has begun despite my feeling severely isolated.

You used to strengthen me totally in any weakness (my specialty), except when occasionally you did not.

I want to increase that communality by leaps and bounds and and.

UNFINISHED

In November of 2013, as the opening of Dover Street Market grew closer, Gins became sicker, though she was evasive about the specifics. She referred only to an illness, which she often called “drear.” “Basically, all I’m getting treated for is toxicity,” she said. “But I don’t want to talk so much about that, because I seem to be conquering it. So, I’m harboring this illness? Oh, maybe, but I seem to be getting stronger, and becoming a very strong survivor.” She insisted we keep meeting, or, if her strength was waning, talking on the phone. She wanted to be certain that I understood as much as possible about Reversible Destiny.

At an appointment with her doctor, Gins was told she would need more chemotherapy. She was rational enough to be concerned about her prognosis, though she still preferred to pour her energy into her work rather than agree to chemo. Privately, she worried she had not pushed the concepts of Reversible Destiny far enough that they would be able to extend her life. She rushed to finish her book, thinking that reconnecting with the ideas in the manuscript might give her strength.

Privately, she worried she had not pushed the concepts of Reversible Destiny far enough that they would be able to extend her life.

Worried that her food could be making her sicker, she cut back drastically on what she ate, teetering on the edge of an eating disorder. Once, when I visited her, she was drinking a pinkish liquid made of raspberries blended with water. She spoke of writing a Reversible Destiny cookbook to disseminate her new ideas about food. She also began to work with an interior designer who told her that he could interpret her dreams and use them to turn her apartment into a more healing space. These were concepts that had never been a part of Reversible Destiny in the past, but as her health worsened, Gins reached for any idea that might possibly work. At night, she struggled to sleep. When she did, she fell into frightening, anxious dreams.

As Gins swung between flagging strength and fierce productivity, her team rushed to finish the construction at Dover Street Market. Post went back and forth between the Market, where she was overseeing the installation of the stairway, and Gins’s apartment, where she checked that Gins had what she needed and talked through a few last decisions to be made about the finishing of the piece. In the days leading up to the opening, Post and several of the Reversible Destiny architects worked nearly around the clock to paint the interior and exterior of the structure to Gins’s specifications.

On the 20th of December, Dover Street Market opened. That afternoon, a small crowd of Gins’s friends and collaborators gathered at the store, eager to see her. Fashion people jostled in the door and wandered through Dover Street’s seven floors, each of which was an amalgam of artistic and architectural styles. From above, Gins’s structure, which she had named the “Biotopological Scale-Juggling Escalator,” looked like a swallow’s nest: the stairs were barely visible underneath the large, curved enclosure. Walking down into the stairway felt like descending into a small cave. The interior was painted a deep purple that faded gradually lighter toward the ceiling. The steps themselves dissolved at their edges into the sandy rammed-earth flooring that Gins and Arakawa used in many of their projects.

Late in the afternoon, Gins appeared, steadied on one side by an assistant. “There’s Madeline,” someone whispered, as her friends clustered around her, kissing her cheeks and clasping her arms. Her clothes hung from her body. She wore all black, aside from a golden scarf draped at her neck and a pair of neon pink bobby socks. Her hair was now a silvery grey, and cropped very short. Post took her hand and led her slowly up the stairs, then down again, as the crowd looked on from below. When she reached the bottom, she found herself facing a tall, well-dressed man. She summoned all her height, threw one shoulder back and raised her chin up at him. “I’m Madeline Gins,” she said. “I made that.” Soon after, she returned home.

Gins spent the last days of December waiting for her book manuscript to come back from a copy editor. She had begun the book with Arakawa, but found that it was very difficult to finish in the wake of his death. Throughout the fall, she had returned to it, making a new attempt to explain her ideas plainly. “You learn that you can’t hint,” she said. “You have to speak directly.” She called the book Alive Forever, Not If, But When. In the first week of January, Gins received the edits, and went over the text one last time.

Three days later, she was rushed to the hospital. Her cancer was so advanced that there was nothing more that could be done to treat it. When her doctor told her the news, Gins wouldn’t listen. She wouldn’t even allow him to leave her room, thinking that his doing so signaled that he had given up on her. When he finally walked out the door, Gins climbed from the hospital bed and followed him down the hall. “See?” she said. “I am still really strong.” Forty-eight hours later, she was gone.

Once both Gins and Arakawa had died, what did their work mean? Collaborators, academics, and friends went back and forth about possible interpretations. Gins had written a will, and made clear that, if she were to die, she wanted the Reversible Destiny Foundation to continue to exist. Many argued that the couple’s project was always meant to be taken metaphorically: although they said they were not going to die, Gins and Arakawa only meant that they would live forever through their books and buildings. Or perhaps their work was just Duchamp-esque provocation, plain and simple. Others, like Post, believed that Arakawa and Gins’s statements had to be taken at face value. “People say, Oh, they didn’t really mean ‘we’re not going to die.’ But I’ve seen it,” Post told me. “Madeline really did not want to die.” I spent hours circling these questions, never coming to a satisfactory conclusion. So one sunny, midsummer morning, six months after she died, I boarded the Long Island Railroad heading east.

Since Bioscleave House was originally commissioned as an extension to an existing home, you enter it by first walking through the entirety of a small, mid-century cottage. At the end of a long hallway is a white and silver door. I pushed it open and Gins and Arakawa’s multicolored universe spread out before me. In the large, circular room that formed the core of the house, an undulating, hilly landscape rose up around a central sunken kitchen. Every surface in my field of vision was painted a different bright color (thirty-eight shades in all). The house lacks interior dividing walls and doors, but four smaller rooms — two bedrooms, a bathroom, and a study — extend off of the main living space.

I ascended a hill along one edge of the room and then skittered down the other side, catching one of the poles that are placed throughout the living room to help people climb and, conversely, to keep them from falling into the kitchen. Cool light filtered through translucent windows, illuminating little particles of dust in the air. I sat down, then shifted onto all fours, figuring out the best way to crawl farther downhill. The building creaked and hummed intermittently, the result of its acoustic design. I made my way slowly to the kitchen. There I could stand easily: the floor in that part of the house is tiled and flat.

A gray box sat on one of the kitchen counters. A title on the front read, “A Crisis Ethicist’s Directions for Use (Or How to be at Home in a Residence-Cum-Laboratory).” Inside were a series of cards printed with a step-by-step guide for the house’s inhabitants. “Vary the size and shape of your body by dwelling into your linkings-up with features and elements of this house,” read one. Or, “Play off of this house like crazy until you have constructed a precise tentativeness for yourself.” I closed the box, a familiar tangle of questions building in my head.

I didn’t understand how Gins could have thought that following these instructions might lead to immortality. But I also couldn’t believe, based on all I knew of her, that she was anything less than serious about the intent of her work. “I saw how unwilling Madeline and Arakawa were to let Reversible Destiny collapse into metaphoric interpretations,” their collaborator Alan Prohm told me after Gins’s death. “In the Western philosophical tradition, death is often posited as the one thing we can truly know,” he continued. “The arc toward dying structures everything that life is, that existence is, that identity is. They took the one thing that cannot be doubted and said, we’re going to doubt it.”

Gins and Arakawa didn’t want to make work that could be easily settled. Hayley Silverman, an artist who assisted Gins after Arakawa died, told me the question of whether or not they intended not to die misses the point. Rather than reading their work like a blueprint, she said, it should be read like poetry. “Part of poetics is allowing things to be said without some relationship to logic or reason or clear understanding,” Silverman told me. “Poetry is a zone of processing. It’s the mind in creation. It’s boring to talk about the logistics of their theory — how it could or could not be true. I don’t think that’s their mission.”

“They took the one thing that cannot be doubted and said, we’re going to doubt it.” —Alan Prohm

The desire to make sense of Gins, to smooth over all the contradictions and chart a direct course through her thinking, is understandable. But it goes against the nature of her project; contradictions are central to her work, and always have been. She and Arakawa created a world in which becoming hesitant and vulnerable would allow you to live forever, where populist ideas could be disseminated through impenetrable texts. Without the contradictions, Arakawa and Gins would have been one-dimensional, a pair of old-fashioned immortality salesmen. Instead, they filled their work with irreconcilable truths. They wouldn’t sell you eternal life, but they would push you to think your way toward it incessantly.

Without the contradictions, Arakawa and Gins would have been one-dimensional, a pair of old-fashioned immortality salesmen.

I climbed back uphill, toward a bedroom. The house felt more hollow than I’d expected. Gins’s presence had the power to alter any room she stood in, to make everything around her feel a bit more charged. I’d wanted Bioscleave House to feel the same way. Gins was the last person to have stayed there. It looked as if she’d left expecting to return in a few days: a small pile of her clothing sat in a corner of the bedroom; nearby, on a table, she’d left a scarf and a dozen bottles of herbs and vitamins. It seemed like she could walk through the door at any moment, saying that she hadn’t died after all. But the house had been untouched for months; a layer of cobwebs and dust covered everything.

Gins often said that the reason she and Arakawa made art and architecture was to “construct optimism.” Their whole philosophy began there, in the desire to embrace being alive and to shift their focus away from the certainty of death. Gins made the choice to believe that art, and her work, were strong enough to do that. It was her version of faith, and her work made that faith solid, physical. Her life, like all our lives, was often filled with sadness and difficulty. There were periods of depression, anxiety, sick parents, financial problems, her husband’s illness and death. Through it all, she insisted not just on continuing to live, but on living forever. Trying to build a world where fewer people suffered made her own suffering bearable. A year and a half after Arakawa’s death, Gins recalled in a letter to a friend her struggle to move forward. “Despite my shattered state,” she wrote, “in spite of the gaping hole that had been punched into my optimism, I asserted that nothing is of more interest than to be alive.”

Amelia Schonbek is a journalist who lives in New York.

This story was co-published with Longreads and edited by Silvia Killingsworth and matt buchanan.