The First Trans Woman in Western Fiction

‘Nightwood’s Dr. Matthew O’Connor was gender dysphoric.

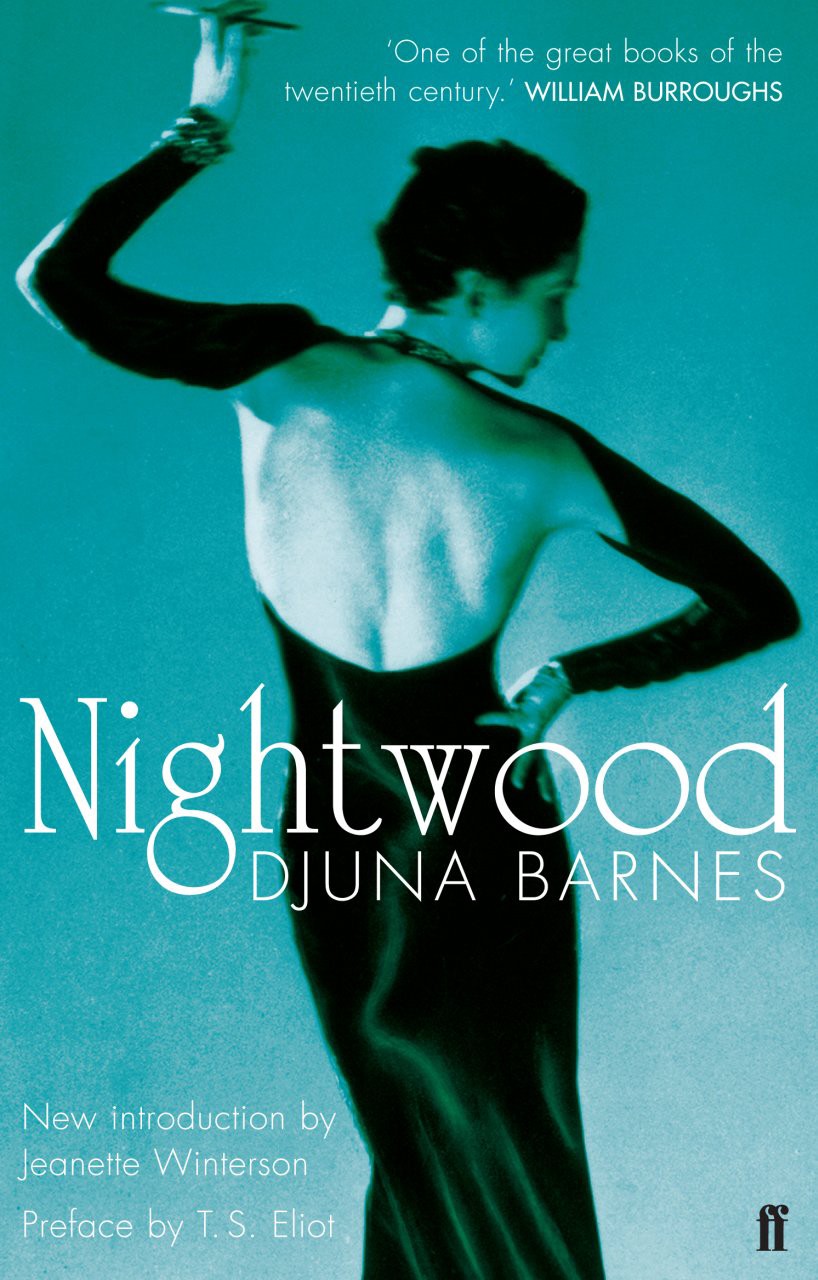

When Djuna Barnes’s novel Nightwood was published in 1936, writing a book that seriously explored lesbian love was a radical act. Thanks to an introduction by its editor T.S. Eliot, the manuscript managed to slip through the censor’s office unscathed. But Nightwood isn’t just a foundational text in lesbian literature; it also contains one of the earliest descriptions of gender dysphoria in western fiction, and possibly the first trans woman to ever appear on the page. In a series of heartbreaking passages, the unlicensed gynecologist Dr. Matthew O’Connor describes being trapped inside a man’s body. Long before words like transgender and gender dysphoria even existed, Djuna Barnes put a trans woman at the heart of her dark masterpiece. Yet like so many trans people today, O’Connor has always been dismissed as a garden variety crossdresser, or worse.

T.S. Eliot said that Barnes was a writer of undeniable genius but questionable talent, while Barnes herself said she was the most famous unknown of the twentieth century. When Barnes began writing the novel she was already a notorious American expatriate living in Paris, and the novel portrays real queer women from the time, including Barnes. Nightwood was born out of the Left Bank literary scene: Paris in the twenties, the Lost Generation. The novel has been called a “cult guide to the homosexual underground night world of Paris that Barnes shared with her lover, Thelma Wood,” depicted in the novel as the barbaric Robin Vote.

If you’ve ever fantasized about writing a tell-all Swiftian novel about your ex, then Djuna Barnes has done you one better. In the biography Djuna, Phillip Herring reported that at least two of Barnes’s close friends physically assaulted her for the way she portrayed them in the book. In the novel’s closing chapter, Robin debases herself by performing a sex act on a dog in front of her rejected lover. Or maybe she doesn’t? It’s that kind of novel.

The book has a loose plot that follows Robin as she ruins one lover’s life after another. While Robin is Thelma’s avatar, Barnes wrote herself into the novel as Nora Flood. Nora, half-mad and lovesick, stalks Robin as she cruises Parisian cafes after dark, until Robin finally abandons Nora for another woman. And whenever Robin wrecks someone, they turn to the doctor for solace.

In one chapter, Nora bursts into Dr. O’Connor’s apartment in the dead of night, only to find him lying in bed wearing rouge, a blonde wig, a woman’s nightgown, and clearly expecting somebody else. After an awkward beat, Nora simply says, “Doctor, I have come to ask you to tell me everything you know about the night.”

And so the doctor launches into a bizarre monologue about how a true connoisseur can tell where a man comes from by the size and excellence of his cock (“and at the Bastille, and may I be believed, they come as handsome as mortadellas slung on a table”). But that comic relief (incredibly obscene for the time) segues into lament:

“‘And do I know my Sodomites?’ the doctor said unhappily, ‘and what the heart goes bang up against if it loves one of them, especially if it’s a woman loving one of them. What do they find then, that this lover has committed the unpardonable error of not being able to exist — and they come down with a dummy in their arms. God’s last round, shadow-boxing, that the heart may be murdered and swept into that still quiet place where it can sit and say: ‘Once I was, now I can rest.’”

And earlier:

“In the old days I was possibly a girl in Marseilles thumping the dock with a sailor, and perhaps it’s that memory that haunts me. The wise men say that the remembrance of things past is all that we have for a future, and am I to blame if I’ve turned up this time as I shouldn’t have been, when it was a high soprano I wanted, and deep corn curls to my bum, with a womb as big as the king’s kettle, and a bosom as high as the bowsprit of a fishing schooner? And what do I get but a face on me like an old child’s bottom — is that a happiness, do you think?

…

“God, I never asked better than to boil some good man’s potatoes and toss up a child for him every nine months by the calendar. Is it my fault that my only fireside is the outhouse? And that I can never hang my muffler, mittens and Bannybrook umbrella on anything better than a bit of tin boarding as high as my eyes, having to be brave, no matter what, to keep the mascara from running away?’”

“We can’t use phrases like gender dysphoria without a huge asterisk,” Dr. Chris Freeman, Board Member of the One Archives Foundation and professor of English and Gender Studies at the University of Southern California, said over the phone. He added, “In terms of the cultural milieu Djuna Barnes was writing about, a lot of people were living very gender nonconforming lives.” When pressed, Freeman said, “You can certainly think of that character, Dr. O’Connor, as groundbreaking. If not the first, definitely the most fleshed out character. What today would be called gender dysphoric.”

The feminist professor Shari Benstock wrote Women of the Left Bank: 1900–1940 in the mid eighties, just as the second wave was dying down. Part history, part literary criticism, the book compiles a lot of the analysis surrounding Nightwood. Yet while Barnes’s closest friends believed she succeeded in giving the doctor a soul, like so many others, Benstock sees the doctor as a pathetic, predatory crossdresser (eventually comparing the doctor to Hitler).

“And must I, perchance, like careful writers, guard myself against the conclusions of my readers?” — Dr. Matthew O’Connor

In a 1990 essay, the British poet Gregory Woods gives us more of the same:

“But he is, above all, an untrustworthy informant, far too much of a man: deceitful in bed, when dragged-up to be penetrated by men, and deceitful at work, when penetrating women under false pretenses. Shari Benstock speaks of how the ‘gossipy and garrulous’ doctor ‘parodies woman’s language, steals her stories and her images in order to teach her about herself’ (Benstock, 1987, p.266). The problem is that, however sincere and convincing his drag, it still conceals the phallus; however brightly lipsticked his mouth, it still contains a patriarchal tongue.”

You don’t have to go searching through Reagan-era literary criticism to find people who believe that trans women are just gay men in women’s clothes. Today, the idea that trans women are perverts in drag acting out an elaborate plot to violate women is a matter of official policy in some states. Yet as Nightwood shows, there have always been people whose identity couldn’t be contained by the gender binary. Trans people have always existed, and we have always punished them for it.

“The gender binary has been one of the most dominant fictions in modern times, and it is a fiction,” Dr. Freeman said. “And finally the fiction is undeniable, finally this idea that masculine equals masculine and feminine equals feminine, is just completely untrue. And you don’t have to look hard in history to see all the places where this didn’t work. That this whole lineup of a one to one gender binary has just never been true.”

During the interwar period when Barnes wrote Nightwood, anyone whose sexuality or gender identity didn’t fit into the heteronormative binary was considered an “invert.” Richard von Krafft-Ebing was a pioneering sexologist who came up with the theory of sexual inversion. The theory was radical, but not so sophisticated as to make a distinction between gender and sexuality.

Unlike Freud, Krafft-Ebing believed homosexuals were born that way, in the modern terminology. Gay men were believed to have a woman’s soul, and “transvestites,” if they were recognized at all, were seen as homosexuals at the extreme end of the inversion continuum. If radical feminists, Ted Cruz, and pioneering nineteenth-century sexologists have one thing in common, it’s the belief that trans women are just gay men in drag.

The interwar period was a time of dramatic transition, and Barnes was hardly the first to write about gender nonconforming individuals. The Well of Loneliness was written in 1928 by a woman named John Radclyffe Hall about a lesbian invert named Stephen. Then there’s Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, which explores gender transformation through the lens of magical realism. Dr. O’Connor has often been compared to Tiresias, the gender bending prophet from “The Wasteland.”

The basis for the doctor’s recognizable personality was an Irish-American named Dan Mahoney, a close friend of Barnes. A description of Mahoney as a drunken barroom philosopher and drag queen cruising Paris between the wars has been passed and watered down through several generations of Left Bank historians. Charles Henry Ford, a writer who once proposed marriage to Barnes, wrote of Mahoney, “what he’s always wanted to be: a big blond with a hundred children. But what he REALLY is he says is ‘just a shrinking violet under a lot of cowshit.’” Mahoney was also the Left Bank’s unofficial abortionist, tending to prostitutes, trust fund artists, and Djuna Barnes. He was a man who believed he was a woman and wanted to be a mother and instead terminated pregnancies.

Before writing Nightwood, Barnes was one of the first American writers to seriously challenge obscenity laws and pioneered participatory journalism. When she was only twenty-two, she jumped off a skyscraper and underwent suffragette-style force feeding in “stunt” articles for magazines like the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Dylan Thomas, T.S. Eliot, and James Joyce were all big fans of her work, although she had beef with Gertrude Stein. According to her biographer Andrew Field, Barnes felt insulted and objectified when Stein said she had “beautiful legs” during their first meeting. Barnes was well known for her beauty, and Field suggests Stein was jealous of the way her partner Alice Toklas looked at Barnes.

But while Joyce, Eliot, Hemingway, and other Lost Generation men are lionized to this day, Barnes has been relegated to cult-author status. Being a woman probably didn’t help. Being known as a lesbian writer (a label Barnes hated) probably didn’t help. And spending the last half of her life as a recovering alcoholic recluse in a Greenwich Village studio certainly didn’t.

Not everyone will enjoy reading Nightwood. Like some of Joyce’s best work, it’s nearly unreadable at times. It can be painfully dark and achingly beautiful, but also confusing as hell. I was sixteen when I discovered Nightwood. I saw a sign in a Borders bookstore that said “Lesbian Literature,” and my sixteen-year-old lizard brain thought, “Ohh, lesbians.” To my disappointment, and unless you have a fetish for obscure modernist prose, there’s nothing particularly titillating about it. And there shouldn’t be, at least not for me. Djuna Barnes wrote books about queer women for queer women. It’s a miracle she was ever published at all.

Early readers were confused by Nightwood too, and not just because of it’s abstract modernist prose. Literary historian Roger Austen wrote that these early readers didn’t understand why the shameless sodomite doctor didn’t have to pay a “suitable penalty” for his “life of depravity”. Of course, the doctor did suffer. At the end of Nightwood, the doctor finally goes mad, driven to despair by his hopeless existence. In Djuna, Herring describes how Dan Mahoney was imprisoned in a Nazi internment camp for being a foreign, gay abortionist.

Now we know better. And while modern gender theory isn’t exactly simple, its application here is actually pretty straightforward. Gay men in drag are both gay and men. Trans women are women. But what about characters like the doctor, men who just know they are women, but never have the chance to transition? Recently, some writers have begun to use the phrase “proto-trans” to refer to people like the doctor, trans men and women who “haven’t transitioned but will someday come out of their shell and be their true selves, unless society prevents them.” We’ll never know the names or stories of the countless proto-trans men and women who died secret deaths, but the least we can do is recognize that they were there all along.

Timothy Beck Werth is a copywriter/editor by day and freelancer by night. You can’t follow him on Twitter.