The Bodies Below the Bar

Money trouble and dwindling membership have plagued the American Legion

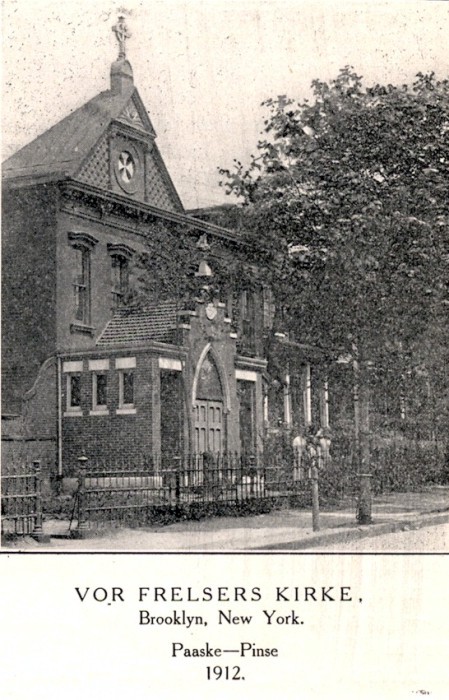

If there’s a bar that should be haunted it’s the Michael A. Rawley Jr. American Legion Post. It sits just above the corner of 9th Street and 3rd Avenue in Brooklyn, an unassuming brick building sandwiched between an Enterprise dealership and a vacant lot. The interior looks a little bit like a barn, albeit a barn with video poker machines. The bar itself is long and sometimes uncomfortably bright since the Christmas lights that hung over the drop ceiling went out and the walls are lined with plaques listing past commanders and departed members. I was hired there about a year and a half ago to tend bar part-time, basically out of pity. The place I’d been working closed down unexpectedly right before Christmas and many of the post’s members knew me from another now-defunct dive bar I’d worked at nearby.

Built in the 1860s as a Danish Evangelical Church, the post sits above an unmarked grave that stretches along 3rd Avenue — the alleged burial ground of the 1st Maryland Regiment. On August 27th, 1776, four hundred soldiers held off the entirety of the British Army in order for George Washington to make his escape during the Battle of Brooklyn. It was the bloodiest battle of the Revolution, and arguably one of the most critical — were it not for the Marylanders we could have lost the war before it had even begun. Chas M. Higgens, a member of the 1914 South Brooklyn Board of Trade, delivered an impassioned speech in defense of the Gowanus Canal, hailing it as the true birthplace of America. “When you passed [the Statue of Liberty] to-day you could have noticed that the face of the Goddess was not turned towards Manhattan or Jersey, but towards the shores of Old Gowanus.”

That’s not actually true — she’s supposed to be facing where the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge now stands, to welcome incoming ships, but it’s still an odd thing to think about in the bar. The Birthplace of America, where someone is wine-drunk and weeping. The Birthplace of America, where two patrons are arguing about who had the worse stroke. The Birthplace of America, where I am forcing everyone to watch The Bachelorette on my birthday. “Listen, I’m not a straight woman, but why in the hell would you wanna fuck a guy named Tanner?” was the Rawley Post’s hot take on the 2015 season of The Bachelorette.

Founded in 1919 to support soldiers returning home from the First World War, the American Legion is a non profit that remains the country’s largest federally chartered veterans’ organization. But as it approaches its centenary, membership is on the decline. Walk into the Rawley Post on any given weeknight and you’ll usually find a few guys drinking at the bar and a pile of uneaten McDonald’s cheeseburgers sitting on a table by the wall. John Lonergan, a long-time member and the current commander of the post, brings them by but he always seems to overestimate his crowd.

The post bought the building in 1962, which should have assured them a measure of financial security, even as Gowanus rents skyrocketed. Lonergan was elected mid-June and took over July 1st, 2016; immediately there were problems. A check for $600, written to a member who’d done carpentry work on the floor and the bathroom, bounced because of insufficient funds. “We thought there was $26,000 in the working account,” Lonergan said. Instead it was overdrawn by $2,000. According to Guidestar’s listing the post hadn’t paid taxes in over three years. None of its members had any idea.

To an outsider, the power structure within the American Legion can seem a little odd. Everyone is called ‘commander,’ the national commander, the state commanders, the district commanders, and the individual post commanders. Even the bar language is militarized. I reported to the lead bartender, whom they called the Bar Captain. As a veteran’s organization the language is justified, but it can seem kind of goofy — a bunch of old men hanging out in their treehouse, arguing over strange internal politics.

Not every Legion has a bar, and the ones that do typically don’t make a huge profit off beer and liquor. Not surprisingly, the members keep voting against raising the prices — at the Rawley Post a pint of Budweiser is still two dollars and an eight-ounce glass is seventy-five cents. Members pay dues every year, but most larger American Legions rent out their back rooms for weddings, graduations, and other parties to bring in money.

At the Rawley Post a pint of Budweiser is still two dollars and an eight-ounce glass is seventy-five cents

When Rawley’s previous commander took over, he brought in a non-member to do the bookkeeping. They quickly took over running the parties in the back room and doing all the ordering for the bar. The bookkeeper, the previous commander, and the former treasurer, all had access to the checking account; as of this writing the Brooklyn District Attorney Frauds Bureau is in the process of issuing subpoenas to them all. “This place has a history of uh…” Lonergan trailed of and shrugged. “People get in here and they have sticky fingers. It’s been looted for years.” Lonergan told me about another former commander — now deceased — who rented out the Rawley Post’s parking lot to a nearby bar and kept the money for himself. Yet another commander was supposedly in the habit of absconding with money from the bar cash register.

Petty theft is hard to prove because up until this point the Rawley Post has dealt primarily in cash, but while skimming money off the top may not be so unusual, large-scale embezzlement is unprecedented. They’ve lost their tax-exempt status, they owe over three years in back taxes, and they’re broke. Checks made out to the liquor and beer companies have bounced, which could get them blacklisted and reported to the State Liquor authority. They’ve got a $200,000 investment that they can’t find, according to Lonergan, who said many of the files are missing and the computer has been locked. When he took over, even the Joker Poker machines had been cleaned out.

They’ve lost their tax-exempt status, they owe over three years in back taxes, and they’re broke.

“There’s so much malfeasance,” said Lonergan, sounding tired. “We went to the D.A. and said we’re not accusing anybody, we don’t know who did it, but we’re broke and we don’t know anything. We wanna take over with clean hands.” The D.A. was not able to comment as to whether there was or was not an ongoing investigation.

Even when rampant theft isn’t an issue, American Legions aren’t doing well across the country. In just the last five years, national membership dropped twenty-three percent; twenty-seven percent in California, twenty-one percent in Illinois, and twenty-two percent in Pennsylvania. The 2016 American Legion convention, where both Clinton and Trump will be speaking, begins August 26th. Trump recently criticized a Gold Star family, so it’s likely that the convention will be somewhat tense, but last year’s wasn’t all smooth sailing either. In the transcript of the 2015 American Legion Convention, held in Baltimore August 28th to September 3rd, National Commander Dale Barnett chewed his subordinates out over membership:

We talked about a culture of growth, and they told me wonderful things. But the reports are not showing that we have a culture of growth. We only have six departments right now that, at this point in time, are ahead of where they were last year. That’s not the direction I want to go as your commander. That’s not the direction we need to go. I know it’s difficult. I know it’s hard. But I know that you want to be on a winning team, and we’ve got to turn it around.

Barnett is a Desert Storm vet who coached high school basketball, baseball, and cross country, and he sounds like it. But he’s right. In just the last five years, New York State membership has dropped twenty-six percent. “The biggest obstacle is really over-saturation of veterans’ organizations that are out there,” said Frank Peters, former New York State Commander. “Back in the sixties there were about four or five, now there are twenty-two just that I can think of offhand. I think we just need to do a better job of advertising, you know. We are the American Legion. We wrote the G.I. Bill.”

Tom Long, who’s been the commander of the Continental American Legion in Queens since 2010, sees the generation gap as the biggest problem. American Legions largely exist in a pre-internet state, so Long has been talking with a young man who was recently discharged from the Air Force about advertising to potential recruits through Facebook.

Chy Mitchell, a retired army nurse and the commander of the thriving American Legion Post 398 in Harlem, credits their success to staying proactive about engagement. She’s also focused on increasing membership amongst female veterans, who have long been sidelined. “If you don’t keep that connection going on it knocks down your membership,” Mitchell said. “Cause then you’re bored. You’re boring. It’s not just a stale thing, you know. You just pay your dues and come and sit and do what? Drink? You can go to any bar and drink.”

Historically, World War II veterans have been the the Legion’s most dedicated base, but that base is aging out. According to V.A. data collected by the World War II Museum about four hundred and thirty-one WWII veterans die every day, and by 2037 they should be gone entirely. The V.A. estimates that there are 22 million veterans alive today, as of 2014 four million of them were post-9/11 vets, but they’re just not joining. “I mean no, right now I’m not worried,” said Craig, a bartender and member at the Bay Ridge American Legion. “But in twenty years…yeah. Then we’ll be in trouble.”

Because American Legions tend to outlast most other businesses by decades, especially in gentrified or gentrifying neighborhoods, they become informal community centers and repositories for weird, outdated gossip. It’s reflected in the peculiar speech patterns of the patrons — tenses and timelines are muddled and unless you push for dates it’s hard to tell whether the events being described happened two years ago or twenty. “I go by — was it before or after I got hit by the car or was it before or after 9/11, those’re my two points of reference now,” Marty Boorman, a Vietnam veteran and retired electrician, said cheerfully.

Stories are told with the oblique, elliptical language of the folktale and repeated to whoever will listen until they become part of the bar’s unofficial canon. The dead never really get to die here because the living won’t stop bitching about them and death is a familiar, even friendly, subject — more because of the patrons average age than their combat experience. Marty tells me about about a cousin of his who got mixed up with the mob and ended up laid out on Ovington Avenue, shot five times.

“The sixth bullet, the guy put the gun next to his head and the gun wouldn’t fire. He was in the hospital fourteen months,” Marty says. “[His wife] had just had a baby. The kid, by the time he was able to get outta the hospital the kid could’ve walked down to church to get baptized. That was the highlight of the christening; the baby and the jacket he was wearing when he got shot. More people were interested in looking at the jacket than the baby.”

Mary Karr famously referred to her father’s American Legion as “the liar’s club,” because of the amount of bullshitting and grandstanding its members did amongst themselves, but she recognized its importance. “Something about the Legion clarified who I was,” she wrote. “Made me solid inside…That bar also delineated the realm of sweat and hourly wage, the working world that college was educating me to leave. Rewards in that realm were few. No one congratulated you for clocking out. Your salary was spare. The Legion served as recompense…You attended the place, by which I mean you not only went there but gave it attention your job didn’t deserve.”

Mary Karr famously referred to her father’s American Legion as “the liar’s club,” because of the amount of bullshitting and grandstanding its members did.

Today, the number of people who care enough to pay attention, much less pay dues, is dwindling rapidly. There’s a tradition at the Rawley Post called sign in. Members write their name on a slip of paper and push it towards the bartender with fifty cents. Every day the bartender pulls a number out of a plastic jar, which is cross referenced against a list of names. If the member signed in the day before, they win the money. If they didn’t, the money is added to the pool. The list isn’t updated very frequently though, so it can be kind of a grim task. Sometimes when the bartender pulls a name, the member has been dead for years.

The Rawley Post is closed Mondays and Tuesday now because of its financial issues — opening on those nights isn’t worth the price of air conditioning. A napkin holder advertising Pharrell’s Qream still sits in front of a Mass Card. Old photos and newspaper clippings cover a bulletin board on the door to the back room. “As Hippies Partied — Meanwhile in ‘Nam,” reads the headline of one article on the evils of hippies. Once you walk in you could be anywhere in the country, but in a building that old, with that many dead bodies around it’s hard not to get a little spooked when the lights flicker.

“Nah,” said Marty, when I asked if the post had any ghosts. He laughed. “Anybody who’s haunting the place is still alive.”

Rebecca McCarthy is an Awl intern and a bookseller.