Being Frank

What Frank Ocean does and doesn’t divulge on his newest record

In 2012, a few days before Channel Orange’s digital drop, I remember my folks asking me why Frank Ocean’s sex life mattered. He’d just alluded to loving a dude in a long note on Tumblr. No one knew how that would affect his career at the time, and the whole thing felt a little bit crazy, but here we were talking about it at the dinner table: my parents, who didn’t do music, and me, the gay boy in training. We had just made it home from church, where we listened to a sermon to the tune of “casting out your demons.” I didn’t have any examples to call on. As far as I knew, dude was doing a new thing. Channel Orange sold over 600,000 copies, and then it went on to win the Grammy and Ocean dissolved into the air entirely.

What I should’ve said was that an allusion to queerness in the public eye wasn’t simply rare in Ocean’s genre — it didn’t exist at all. It’s not really something that mainstream black male artists do. And of course, I could’ve mentioned Little Richard’s occasional nods to camp, or Prince’s cultivated gender fluidity, and I could’ve mentioned Hendrix and I could’ve mentioned Whoever Else. But most of these guys took from a culture they weren’t much invested in, to say the least, on their quests to unbutton the flies of the opposite sex across the glove.

But Ocean found a way to adopt queerness for queerness’s sake. There was no obvious ulterior motive. It just felt like he needed to get something off his chest. There’s a line on Channel Orange’s “Forrest Gump” that feels like a case in point:

I know you Forrest

I know you wouldn’t hurt a beetle

But you’re so buff and so strong

I’m nervous Forrest

Black men are a lot of things on record, but they aren’t nervous. And yet here he was. And to another man, of all people. There’s a similar ode on Blond(e). Except now Ocean’s a grown-ass man. He knows better, if not more, about what he’s getting into:

I’ll be the boyfriend in your wet dreams tonight

Noses on a rail, little virgin wear the white

You cut your hair but you used to live a blonded life

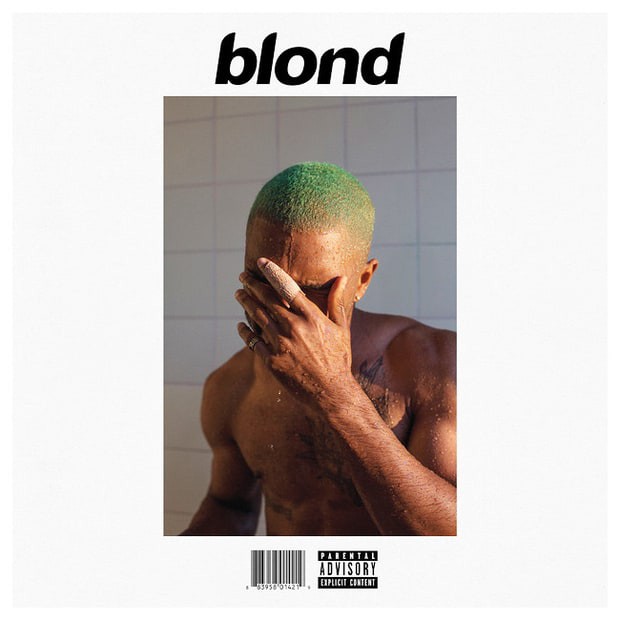

You can’t really talk about Blond(e) without bringing at least a little attention to the rollout. A smooth four years passed between albums. It dropped on the heels of a whole other record, “Endless,” a visual album that’s basically a forty-minute set piece. First, there’s the obvious issue of the discrepancy in the record’s title, donning the ‘e’ in some places and dodging it in others. It could be a nod to the tug of the word’s femininity, and an aversion to that very same notion. It’s another riddle Ocean’s given us to solve. Blond(e)’s cover is its own beast, and the thought underlying its presentation is worth at least as much scrutiny as the record itself. But Ocean hasn’t given us a whole lot to go with here — you could fill a Reddit thread or nine with the underlying connotations of cars, cocaine, a lover with blonde—or blond—hair.

It’s not like Ocean has been silent between release dates. He showed up on just about everyone else’s albums. Immediately after the Pulse shootings, Ocean penned an open letter (noting, among other things, “We are all God’s children, I heard”). He wrote a screenplay for a TV show, called “Godspeed.” In the video for “Endless,” we watched him hammer a staircase. He teased us all on Twitter with the record’s release date, and not even under his own handle (he doesn’t have one), he had half the world bugging over a release date he himself never gave.

There are the incidental notes too. Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar appear on Blond(e), but their roles are peripheral at best. Bon Iver hums in the background. Yung Lean and The Hollows’ Austin Feinstein streak across the same track, and André 3000 comes through for a literal minute to break the door down. Jonny Greenwood and James Blake fluttered their hands across the album. David Bowie, Elliot Smith, and the Beatles are listed in the credits, but Ocean doesn’t explain how or why they’re incorporated. They hide in song titles, and in phrases murmured offhand.

Ocean is a pretty private guy; he really only fucks with Tumblr. But Blond(e) is an extremely personal record, and we’ll be dissecting exactly just how much of himself he’s shared with us for some time. On “Good Guy,” as the track whispers in under a handful of chords, Ocean relays an anecdote from a sore date:

Here’s to our good guy, he hooked it up

Said if I was in NY I should look you up

I, first time I done saw you

You text nothing like you look

Here’s to the gay bar you took me to

Here’s when I realized you talk so much more than I do…

I know you don’t need me right now

And to you it’s just a late night out

On “Ivy,” Ocean riffs on surprise, and the unexpected allures of affection:

I thought that I was dreaming when you said you love me

The start of nothing

I had no chance to prepare

I couldn’t see you coming

That vulnerability kept taking me out throughout. This isn’t a radio record . For some artists, I’d expect it, yeah, but from guys who look like Frank Ocean—like me? And on the year’s most anticipated release? Nah.

In most camps, the quality of the music itself was never called into question. You and I didn’t for a second think that the release date was pushed because he couldn’t pull it off. Blond(e)’s got layers, it gives answers to questions that we weren’t asking before. It takes the notion of R&B and ‘black music’ and whatever we thought that meant and flips it on its head. The silences and breaks are maddeningly calculated. Some gaps bloom silently for one, two, three seconds, while others expand into flourishing arpeggios (there is a lot of guitar on the album). The drops, when they do come, are devastating. “Nights” in particular features at least one notable shift, in the middle of the track, at least a little bit reminiscent of Channel Orange’s “Pyramids.” The record is inscrutable in swathes. But you could probably also get laid to at least half of it too.

Much has been made out of his notes regarding the car imagery plastered on Ocean’s mixtape Nostalgia, Ultra, and then again in pockets of Channel Orange, and again in Boys Don’t Cry, a magazine Ocean released in conjunction with the records. It’s got poetry (a piece from Kanye West concerning McDonalds), an abundance of art (featuring men and women, naked and not), and cars and cars and cars. He alludes to the vehicles connoting a certain brand of masculinity. Ocean’s since claimed it could link to a deep subconcious straight-boy fantasy (“Consciously though,” he adds, “I don’t want straight. A little bent is good too”).

Except that he doesn’t much care to elaborate on that either. Or if he does, he’s having another conversation entirely. And maybe that’s the calling card of a really solid-product: we become at least as concerned with the guy underlying the tracks as the record itself. How could he make this? What’s going on his head? A fuck-ton, but Ocean knows exactly what to show us and what not to.

A woman who sounds a lot like a mother admonishes someone who sounds a lot like Ocean on the record’s fourth track. Her tone’s just as scolding as the other mother, on Channel Orange’s “Not Just Money”. This time, she encourages him to be himself, to stay away from the pot and the alcohol and the bad influences that would take him away from whoever that is. She tells him that he knows who she is. She tells him that he should listen. She taught him right. And yet, on the next song’s very first verse:

Hand me a towel I’m dirty dancing by myself

Gone off tabs of that acid

Form me a circle, watch my jagger

Might lose my jacket and hit a solo

The first time I heard this bit, I thought, Oh. This is where he grows up. That’s what the album’s about. Even if it means stepping away from whatever he’d grown up thinking he should be. What will never not be fascinating to me is how this dude from the Seventh Ward takes what is arguably the most homophobic genre on American airwaves and turns it on its head.

Blond(e) ends on a very different note from the one it begins on. We’re left with a dialogue from his younger brother, Ryan at eleven years old; he’s not all that much older now — and he’s fielding questions about the future from some kid. The kid asks Ryan about his earliest memories (speaking his first words) and the most amazing thing he’s ever seen (friendship). The conversation comes on the heels of a melody rising like something a little more akin to Radiohead’s Kid A than anything else, where Ocean notes that “now I’m making 400, 600, 800K momma, to stand on my feet”:

They paying me momma

I should be paying them

I should paying y’all honest to God

I’m just a guy I’m not a god

Sometimes I feel like I’m a god but I’m not a god

It’s a telling assertion. Across The Life of Pablo, Kanye flaunts his god-status, and on Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book, he nods in deference to the Holy, and on Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, he returns again and again to the randomness/specificity of His will. These men stake their allegiances and their parallels and their trifles with the holy.

Ocean feels like God. But he knows that’s not. But knowing a thing isn’t true doesn’t evaporate the thought, and maybe this was Frank’s mission, what it is that he’s getting at — the space between labels and certainties and declarations. He’s shown us that there’s a space for that, too. It took him a while, but he’s found it. The result is the sound of the past four years, of the waiting for this thing — it’s pretty clear that Ocean’s been waiting with us, too. And whether or not you concede that the album was one worth waiting for (I do), it’s certainly one worth living with.

When I heard the record came out, I listened to it all the way through. Then I left my place for tacos. I didn’t listen to shit on the way there; I felt a little dizzy. Then, back in the car, I parked at a gas station, and tried the record again, and then again the next morning, and then I called my mom. I told her something amazing had happened, that I’d finally gotten her answer — four years later. I asked if she remembered (she didn’t). But she still humored me, she asked why, and from who, and I told her Frank told me, I said I think he’s figured it out.

Bryan Washington divides his time between Houston and New Orleans. He is working on a collection of short stories.