Wring Out Your Dead

A Chicago funeral director is championing a modern method of body disposal

Elizabeth Fama, a writer from Chicago, had been considering the different ways to dispose of a body after her mother-in-law, Lydia Cochrane, died. A traditional burial was off the table: Pumping her mother-in-law’s body with toxic embalming fluid on top of a pricey funeral didn’t seem right. Cremation was her next thought, but Fama didn’t like the idea of placing Cochrane’s body into a 1800℉ chamber, creating the same greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change. She chose a third option, which she read about online, a process formally known as alkaline hydrolysis—most people call it flameless cremation.

Cochrane’s body was wrapped in a silk shroud and placed inside a machine that looks like a chrome-encased iron lung. A combination of water, lye (also known as sodium or potassium hydroxide), and low heat gently circulated over her body until it was dissolved into a coffee-with-cream-colored liquid. It cost Fama about the same as cremation, but left a fraction of the carbon footprint. “There’s no reason to say no to it, except that nobody knows about it,” Fama said.

The process of dissolving a body takes four to eight hours; families can be involved or not as they wish. For Fama’s family, that meant helping seal the machine and pressing the start button. “Even though pressing a start button seems like a small thing, it’s actually a big emotional moment,” she said. Instead of reducing the body to ashes with intense heat, alkaline hydrolysis uses a chemical reaction to digest the soft tissues into a sterile fluid that is later discharged to the local wastewater-treatment facility. Bones don’t dissolve because lye doesn’t have the same digestive reaction with calcium phosphate; instead, they are dried and pulverized into a fine powder that can be stored in an urn: not-quite ashes.

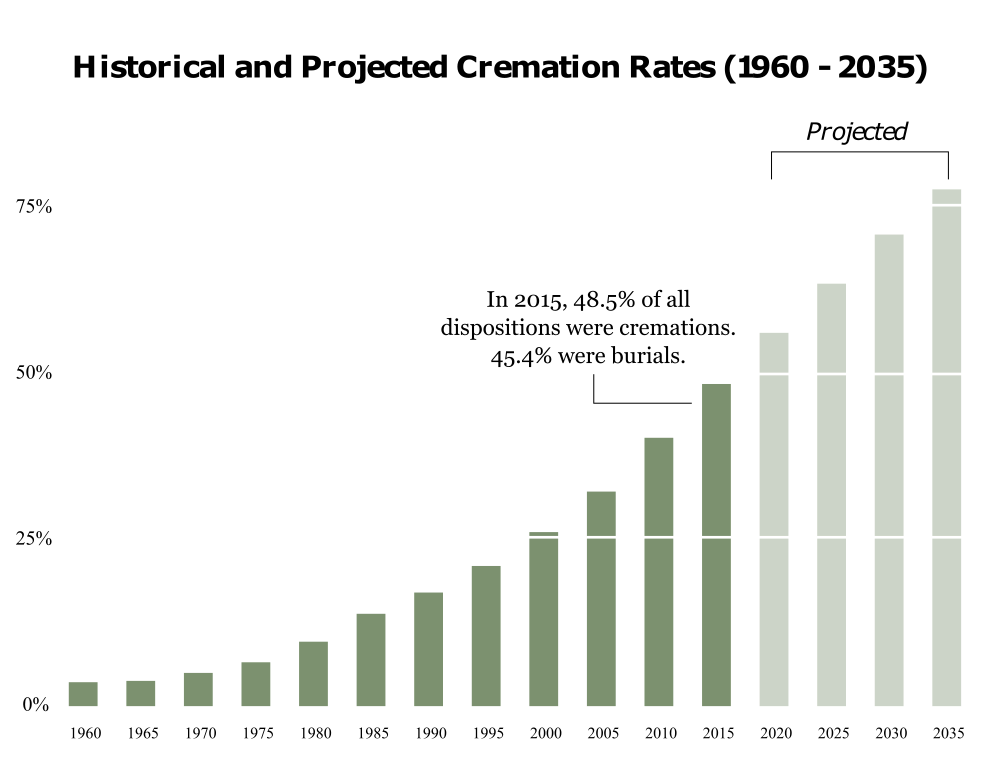

Over the last fifteen years, the rate of cremation has nearly doubled. And in 2015, for the first time ever, more people in the United States were cremated than buried. With more families forgoing expensive funerals in favor of cremations, flameless cremation stands to gain ground as a third, cheaper and more efficient option.

Ryan Cattoni, a funeral director based near Chicago, is the owner and operator of AquaGreen Dispositions, Illinois’ first and only flameless cremation provider—the same one that handled Lydia Cochrane’s service. It’s one of only five funeral homes in the U.S. that offers the service. Cattoni believes flameless cremation will disrupt the business of what we do with the dead. “It’s greener and more environmentally friendly since there are no air emissions in the process,” Cattoni explained, adding that his service uses 90 percent less energy and more than 75 percent less carbon output compared to traditional cremation.

Another advantage of flameless cremation is that elemental mercury from dental amalgam fillings isn’t vaporized, as in a traditional cremation. Also, there is no “bone commingling” — a side effect of traditional cremations, where it’s difficult to sweep out 100 percent of the ashes from awkwardly shaped cremation chambers. Lastly, the leftover fluid does not contain DNA or genetic material because the bonds in the nucleic acids are broken down.

If you drew a Venn Diagram of Cattoni’s clientele and Prius drivers, you’d expect a one hundred percent overlap. But Cattoni explained that the only thing his customers have in common is that they don’t like the idea of their body being buried or burned. None of them knew they had the option to be returned to the earth by water instead of fire before meeting Cattoni. “I think it’s just a little easier on the mind,” said Cattoni.

As a twenty-seven-year-old first-generation funeral director, Cattoni is an anomaly in his field. Cattoni only began to consider the profession after his grandfather died. He remembers how the funeral director, who handled the service, made it a littler easier and a lot less stressful for his family. “I figured if I could do that for other people, I’d truly be making a difference in somebody’s life,” said Cattoni, who enrolled in mortuary school after finishing high school.

Cattoni first learned about flameless cremation in 2010 while working to obtain his funeral director’s license. He came across an article in a trade journal describing the Mayo Clinic’s use of the process for their donated-body program. In 2012, when he was just twenty-three, he worked with state lawmakers in Illinois to pass legislation to legalize flameless cremation. That same year, after the legislation passed, Cattoni purchased a machine (which can run anywhere from $200,000 up to $450,000) and launched his own company. At first, business was slow. Cattoni’s mom helped with front office paperwork and his dad lent a hand during the procedures — all of which helped sell Elizabeth Fama on the idea. “It’s actually very comforting…to come in and see this family operation,” Fama recalled.

As word spread, so did demand for Cattoni’s service. People’s ears perked up whenever he mentioned flameless cremation. “It sparks an interest in people,” he said. Last year, AquaGreen Dispositions doubled its business. Now, families from Tennessee, Michigan, and Wisconsin are bringing their deceased to Illinois for a flameless cremation service.

In the next three decades, America’s sixty-five-and-over population is expected to double. The funeral industry will have to accommodate, and Cattoni is betting that more and more families will opt for his services. The last sea change of this scale came in 1963, when the Catholic Church lifted its prohibition against cremation. As environmental consciousness penetrates public dialogue, flameless cremation could be the way of the future. Fama compared Cattoni’s entrepreneurship to a young CEO in Silicon Valley. “He skipped right over the boring old mortician generation and went straight to what young morticians should be like right now,” Fama said.

Not everyone is on board with the new wave of body disposal. Flameless cremation is illegal in all but ten states (Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Oregon and Wyoming). In 2012, the New York State legislature voted on a bill to legalize it, but ran into opposition from the New York State Catholic Conference. Before the bill was defeated, the Conference wrote in a memo, “It is therefore essential that the body of a deceased person be treated with respect and reverence. Processes involving chemical digestion of human remains do not sufficiently respect this dignity.” Last week, a communications rep confirmed by email the organization maintains that position.

Even in places where it’s legal, details on flameless cremation are hard to come by. David Weber, a funeral director from Baltimore, Maryland, believes that there isn’t enough information out there to give an informed opinion on the process. “Many of us feel that there needs to be a little bit more research…we know what the impact is for cremation, but were not certain what the environmental impact might be for alkaline hydrolysis,” Weber said.

A public relations manager from the National Funeral Director’s Association said over email that the organization does not take a position on the procedure. But it’s hard to imagine they’d be excited about anything that would eat into the ever-shrinking number of profitable funerals. In 2014, the median cost of a funeral was around $7,000. Cattoni offers transportation of loved one from place to passing, two copies of the death certificate, the service itself, and an urn for $1,795.

The main obstacle Cattoni faces in pursuit of growing his business is misinformation. “Some common things people say is that the body is placed in a vat of acid,” said Cattoni. Which couldn’t be further from the truth—literally. (Remember, the process is formally called alkaline hydrolysis—an alkali is a base , the opposite of an acid.)

Late last month, several Canadian news outlets ran stories with headlines like, “Smiths Falls, Ont., funeral business dissolves the dead, pours them into town sewers.” The sensational article described the work of a funeral director named Dale Hilton from Ontario who specializes in flameless cremation. Coincidentally, Hilton’s business is also called AquaGreen Dispositions — the same as Cattoni’s. A lot of people, including me, emailed Cattoni, thinking he and Hilton were the same person. “I’m the original AquaGreen Dispositions and I guess that [Hilton] liked the name so much that he decided to use it in Canada too,” Cattoni said.

The future of flameless cremation depends on whether the public can be convinced that it’s a responsible thing to do. When Cattoni isn’t working, he’s talking to anyone who’ll listen. “I go and do seminars whether it’s for one person or 100 people. It doesn’t matter,” said Cattoni. “The funeral industry is a very slow changing industry, I will say that,” he added. For better or worse, Cattoni will be around to see it. When his own time comes, Cattoni said he’s “definitely” going flameless.