Reality Hunger

How Big Food manufactures authenticity in an artisanal world

A.1. Steak Sauce, never artisanal and not once locally made, is currently the subject of a campaign that touts it as a secret ingredient to a compound butter with which to finish your steak. It’s a very straightforward commercial: no fancy CGI talking steaks, no dizzying smash cuts, just a peppy-but-smooth voiceover narrating a recipe as a handsome-but-friendly young man in a chef coat makes a butter with A.1. rolled into it, and then makes a steak that is then finished with a knob of said butter. The final image is the product and, whoa — correction, the product is not A.1. Steak Sauce but now A.1. Original Sauce. Because what self-respecting foodizen would buy a mass-produced product just to pour it onto a steak? This is no longer a condiment (a condiment that goes back to 1831 in what we then called “England” whose secret ingredient is raisins, shh) but a fancy home-cooking ingredient to be integrated into your haute cuisine while you sip blue wine and make Tronc jokes, wittily.

It wasn’t that long ago that chocolate bars made from cocoa beans sailed to the States on a three-masted schooner were some sort of novelty, and the word locavore was designated a word of the year. But as foodie culture has matured and become less an underground movement, commercially mass-produced food products swollen with HFCS and other test-tube names — along with the small number of multinational food and beverage conglomerates, such as The Kraft Heinz Company (which is what remains after a series of mergers and acquisitions of formerly independent and iconic companies, and not coincidentally the owner of A.1.) with concentrated influence, sometimes referred to as “Big Food” — haven’t exactly gone away.

We live in an age of high-end food magazines and journals actually starting and not shuttering, and an entire sub-industry of TV shows with adorable tykes cooking for judges, a time when everyone has at least one friend who tsks when you disclose that you use dry yeast and not a home-cultivated starter to make your Asiago Di Parma babka sticks. How is Big Food keeping on keeping on, and how do they like Twitter?

Food is better than food has been ever before. Ask anyone! Or go have some food, perhaps at a pop-up or a food hall. After a long omnipresence of industrially manufactured shelf-stabilized product, better and healthier food is slowly making its way to more and more tables. Big Food has for better or worse largely solved issues of food scarcity in America — in the historic sense of growing/manufacturing and eventually processing enough calories that will not spoil before it can be delivered to an entire nation. (This victory over scarcity is not to be confused with food deserts, which are in many ways the intended result of Big Food’s ubiquity.)

But all is not so sanguine in the boardrooms of Big Food. In fact, they have a multibillion-dollar problem: consumers are looking for, and buying, alternatives to the processed, packaged, middle-aisle foods that have been so popular for so long. Packaged-food sales in the U.S. are falling at a rate of 1% a year, which doesn’t seem like very much, unless you are a brand manager for Big Food. At the same time, annual sales of organic food are increasing at a steady clip. Consider annual sales topping $100 billion for the first time in 2014 for the “specialty food industry” (generally speaking, small purveyors of upscale food products/fancy hippie stuff). In that same year, 82% of those sales were made in mainstream stores — your Walmarts and Costcos and drug stores and grocery chains. The fancy hippie stuff that used to haunt the co-op or the local health-food store for is increasingly bought and sold in places where Big Food once had no competition.

Since 2005, Americans have been making healthier food choices, reflecting efforts through advertising and product labeling to make consumers aware of the nutritional value of whatever is for lunch and dinner. Meanwhile, a robust foodie culture buttressed ideas of wellness in food with a patina of authenticity. Before there were foodies, there was a near-century of home-kitchen gourmands, like M.F.K. Fisher and Julia Child and James Beard (and even Vincent Price!). First with the written word and later with television shows, they pushed a proto-DIY sensibility about foods that were traditionally the province of fine restaurants. By the end of the Reagan years, the Slow Food Movement coalesced, a quiet revolution against fast food and fast life (and, in a sense, modernity), bringing what could now be called a concept of self-care into gastronomy.

And this authenticity has blossomed into the food culture we know now — an army of heavily tattooed chefs willing to risk being Chopped, followed from opening to opening (to book-signing) by a food-buying public right behind him or her that increasingly wants to eat less processed, fresher, and healthier food. Americans are now looking to food to provide something more than convenience, whether sustainability, health, cultural cachet or extravagance, all aspects of authenticity that can be summed up as, “Not Big Food.”

One tactic of Big Food in reacting to a consumer sentiment leery of Big Food is to go out and subsume specialty and organic food manufacturers into their conglomerate maws like so many chili-cheese flavored baked corn potato snacks. True, some of the organic food companies have sales numbers that put them in the same league with traditional food companies — Hain Celestial Group (Celestial Seasonings, Spectrum coconut oil) booked $752 million for the first quarter of 2016, and Bob’s Red Mill is estimated to pull in $200 million per year. But many of these heavy hitters play for the other team. Alexia (gourmet frozen foods) joined ConAgra in 2005, and Blake’s All Natural did the same in 2015. LaraBar landed with General Mills in 2008, Stacy’s Pita Chips has been part of PepsiCo since 2005, JAB Holding Company acquired luxe coffee concerns Stumptown and Intelligentsia in 2015. And in the most extreme example of dissonance, presumably “natural & organic” meat purveyor Applegate Farms was acquired by meat processing giant Hormel Foods in 2015. If you can’t beat ’em, buy ‘em.

To the extent that authenticity cannot be purchased, Big Food is trying to surf it. Legacy food products, filled with efficient ingredients developed over generations for ease of manufacture, product shelf stability, taste, etc., are being changed: synthetics removed, and artificial colors eschewed. In some cases, the recipes are tweaked in an effort to transmogrify the irretrievably dated food product into something cool, or at least approaching cool. Take for example Hot Pockets, which have collaborated with food trucks to roll out a new line called Hot Pocket Food Truck Bites (Triple Cheesy Bacon Melt Bites! Spicy Asian-Style Beef Rollers! Etc.), a clumsy name but a very earnest co-optation of foodie culture, brought to you by the Nestlé Pizza and Snacking Division, Nestlé USA, which is also a clumsy name but at least transparent. Big Food getting into the Stoner Stunt Meal business is nothing new (especially in the fast food sector), but Hot Pocket Food Truck Bites simultaneously achieves full munchie while lolling under the umbrella of food truck authenticity — i.e., yes it sounds gross; would eat.

One iconic dry dinner-mix brand that finds itself at this particular crossroads is Hamburger Helper (which by the way is now known as just “Helper.”) Three years ago, General Mills updated the brand to “appeal to Millennials,” such that the Tuna Helper and the Chicken Helper joined Hamburger Helper as just plain Helper. This is not to be confused with an indie rock band. Or is it? But it is a deft little transition from pure nostalgia, all orange vinyl and fake wood panelling, to a swell foop of attempted memetic content, something that is easy to imagine as a favicon or an app button.

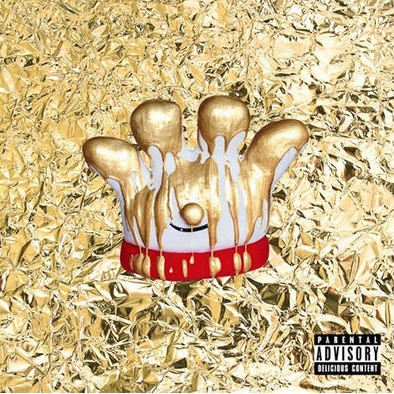

A few months ago, Helper dropped a mixtape called Watch The Stove on Soundcloud. Even assuming a baseline of news-aggregation churn, it grabbed some headlines and murdered some favs. As of this month, the first track has been played six million times, while the last of the five tracks has hit close to 600,000. Thought it was release on April Fool’s Day, it was well received, with some critics noting that it was “among the year’s best mixtapes” and “pure goofy fun” and “shockingly great”/”shockingly good.”

It did not take long for the official version of the secret origin of the HH Mixtape to hit AdWeek (and a bit longer for the music-focused version to run): General Mills has a scrappy if not heroic in-house agency dubbed The BellShop. “Our creative officer was like, ‘Trust the kids, let it happen,’” communicated Liana Miller, marketing communications manager. Of course he was! “Let’s make something we would listen to, not some marketing ploy,” said the Millennials in the house. A little ingenuity and a half-dozen or so “up-and-coming rappers and social influencers” later, and voila, a little widget full of music and fun and authenticity was unleashed to adoring fans.

Authentic, you could say, which circles us back to where we started. An aging Food Product — which actually can never be retro-locavored or whittled into some version of bespoke because it was always intended to be a convenient food from a box and not a twinkly dream-catcher of nature’s bounty — is dragged into authenticity by the authentic efforts of some authentic ad kids who authentically love rap music.

Or is it Authentic, but in scare quotes? As the Minnesota Star-Tribune reported on the brand reinvigoration in 2013:

Mills plans an advertising blitz for Helper starting this month. The campaign will include digital, a space in which General Mills is often aggressive, but hadn’t been with Helper. The brand got a Facebook page only in December. Digital would seem vital as General Mills tries to broaden the marketing of Helper to a younger demographic — 20-somethings, particularly men.

As recently as June 2014, this relaunch was not going so well. Helper specifically was lagging, showing no increase from the sales numbers that inspired the Helper-ification of Hamburger Helper. Eighteen months later, creatives scurried around Minneapolis, lining up tracks honoring the dry-dinner mix.

Another bit of history that makes this cheese more binding is that, among the upscale gourmet concerns bought by General Mills was Annie’s, in 2014. And while it might turn your stomach to know that your dollars supporting gluten-free goldfish-shaped crackers are actually going to Big Food, it could not have gone unnoticed by the Helper crew, as the prepared macaroni-and-cheese product that supplanted the blue boxes of Kraft in so many homes, the market-gobbling competitor to Helper, was now married into the General Mills family. Helper was increasingly the odd cousin with funny taste in clothes that the second and third cousins whisper about.

Does the fact that this accident of authenticity was not so accidental make it any less authentic? In a sense, the question is analogous to, “Does knowing how the sausage is made make it any less sausagey?” But sausage does not purport to be anything other than sausage, and if authenticity really is manufactured, then that’s a bit of conceptual crossing of the streams, which brings us to the central question of whether a Big Food food product can still have it all in these modern times.

Compound butter is not the first non-steak use that has been marketed for A.1. In the 80s, there was a protracted campaign imploring America to put that stuff on a burger, and in 1963 A.1. ran a truly visionary spot with many hors d’oeuvres suggestions, including a “cream cheese sundae” that is nothing but a pile of cream cheese with A.1. as the “fudge” — for dipping! Big Food was crafty about how to trick people into buying their product even back when it was a bunch of Little Foods, and there is always a peg, like affordability, or flavor, or convenience, that this advertising and marketing is hung on. The pervasive such peg right now is authenticity, and as we navigate what’s for dinner, we are confronted with questions of authenticity, whether intrinsic or bestowed.

And the authenticity of Helper, or A.1. Original Sauce, or Hot Pocket Food Truck Bites, is as authentic as every other artifact of a non-authentic time. Faking it is the new bringing it, and it’s not just the hundred or so thousand people who know what a “tech bro” is who are now the targets of creative class employed by Big Food (who also know what a “tech bro” is), but rather the millions and millions of consumers who follow behind, who just want to listen to a mixtape and think to themselves how turnt/lit/woke it is that there’s a Hamburger Helper mixtape. There are forces of capitalism at work here, or at least forces of greed. General Mills isn’t going anywhere, in the same sense that The Banks aren’t going to spontaneously break up.

Helper and A.1. could be retconned out of existence and the world would keep turning. When discussing issues of nutrition or sustainability, the fates and fortunes of Big Food legacy products are irrelevant, but for the fact that they actually do exist and presumably people are employed manufacturing and marketing and distributing and retailing them and a bunch of people certainly like eating them — I like eating them. Five years from now, there will be another course of events that will be take-worthy concerning Helper or Hlpr or whatever the name morphs into, at which time there will still be fans listening to “Watch the Stove” and reminiscing.