Jam Jockeyed

Why You Can’t Escape “Seven Nation Army.”

In the winter of 2012, Deadspin published a meticulous reconstruction, written by Alan Siegel, that detailed the transformation of The White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army” from sound-check noodling into arena anthem. Siegel traced the burgeoning U.S. American use of the song’s main riff as a European-football-style chant to, well, a European football match.

In 2003, Belgian soccer fans in Italy, there to watch Club Brugge K.V. against A.C. Milan, overheard the song in a bar before the game. The Belgians started singing along to Jack White’s syncopated, circular riff, continuing as they headed through the streets and into the stadium. (That is, they weren’t so much singing the song as they were emulating its guitar part; no lyrics necessary.) After Club Brugge defeated Milan, “[t]he song traveled back to Belgium with them, and the Brugge crowd began singing it at home games,” Siegel wrote. “The club itself eventually started blasting ‘Seven Nation Army’ through the stadium speakers after goals.”

From there, the riff-cum-chant gained a foothold with supporters of the Italian club A.S. Roma, and then with the Italian national team — who would go on to win the 2006 World Cup. Siegel identified a public radio story and the ministrations of marching-band arrangers as the means by which the song leapfrogged into U.S. college sports, first at Penn State, then at Boston College, then Ohio State and Michigan and everywhere else. It was only a small step into North American men’s pro sports. “Seven Nation Army,” the Deadspin headline declared, had “Conquered The Sports World.”

Setting aside the fact that what “Seven Nation Army” had conquered wasn’t so much the world as it was the North Atlantic, what no one could have known then was that the tune was still on the ascent. Forget the military metaphor; “Seven Nation Army” didn’t advance by siege and flanking maneuvers. It spread like a weed.

Which is how, on Saturday night at the Chesapeake Energy arena in Oklahoma City, it ended up hoarsening the throats of Thunder fans as they urged on their team’s doomed attempt to hold off a surging Steph Curry and the Golden State Warriors in the N.B.A. Western Conference Finals.

If “Seven Nation Army’s” leap from record to grandstand began in one Milanese bar with a single pack of Belgian diehards, its proliferation in North American men’s pro sports, like the invention of calculus or the telephone, is a case of multiple discovery.

Early adopters of “Seven Nation Army” in the U.S. included the N.B.A.’s Milwaukee Bucks, and the N.F.L.’s Detroit Lions and Baltimore Ravens. The Bucks’ special cheering section called Squad 6 — dreamt-up and financed by the Australian center Andrew Bogut, who now plays for the Finals-bound Warriors — may have been the first to chant it as a signature. This message board thread, from 2009, captures the very moment Bucks fans hatched the idea. In an email, Johnny Watson, Bucks Director of Live Programming and Entertainment, confirmed that the team had played the song as early as 2006, using it as an invigorating entr’acte between the third and fourth quarters of home games.

Squad 6 members seem to have known the riff and routine from European soccer. In the the message-board thread, one member writes that he sent Bogut a popular Italian remix called “The Concert” by M@d; it was reportedly well received. Bucks fans were also aware of college football’s growing penchant for the song, especially in the midwest, mentioning Ohio State as a model in particular. Likewise, Detroit Lions fans probably drew on the “Seven Nation Army” tradition established at the University of Michigan.

Ahead of the 2011–2012 hockey and football seasons, the song extended two other tendrils into North American pro leagues. The N.H.L.’s Ottawa Senators chose an EDM-infused version as their goal song, and, in what would turn out to be a pivotal event, the Baltimore Ravens adopted the chant by fan vote. “I lobbied hard for ‘Seven Nation Army’ to be in the mix, because I had seen it work in Europe. So I thought, ‘if we bring this to the states it could be really cool,’” Jay O’Brien, Director of Broadcasting and Gameday Productions for the Ravens, told me. O’Brien had learned the song while studying abroad in Rome.

The Ravens debuted their loudspeaker-edit of White’s riff on an occasion shot through with emotional significance: a home opener, held on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, played against their arch-rival, the Pittsburgh Steelers. As the Ravens bullied their way to a 35–7 victory — avenging the playoff loss that ended their season the year before — fans, players, and coaches embraced “Seven Nation Army” in real time. “John Harbaugh [the Ravens’ head coach] and the players were up on the screen while we were playing the song, and they were into it, so the fans got into it,” O’Brien said.

“If we didn’t have that game on that day with that song, I don’t know if it would have happened,” said O’Brien, “I had the time of my life at that game, and I think everybody else did, too.”

The Ravens’ adoption of the song had two important consequences. First, the chant soon crossed Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard to join the Orioles at Camden Yards, granting it a perch within Major League Baseball. This kind of exchange wasn’t unprecedented in Baltimore, whose althetosphere is sometimes branded “Birdtown” for the weird avian synergy of the Ravens, Orioles, and — if you’re of the patrician class — NCAA lacrosse’s Johns Hopkins Blue Jays.

The second — and decisive — consequence was that Baltimore’s raucous version followed the team all the way to their 2013 Super Bowl victory. A few months later, the Miami Heat would claim the N.B.A. title after a season in which the song accompanied the home court introduction of their lineup, led by LeBron James, Chris Bosh, and Dwyane Wade. “Our fans had been chanting the ‘Seven Nation Army’ chant for a number of years kind of organically. And we thought it would be a great opportunity,” Heat Executive Vice President and Chief Marketing Officer Michael McCullough said, “so we pursued the rights to sync the song to a video.”

The introduction, and “Seven Nation Army,” became Miami trademarks. But trademarks can also be targets, as the Heat learned when San Antonio fans trolled them with the chant after the Spurs took game three of the finals, 113–77. It wouldn’t be enough to stop Miami, though, who’d go on to win the series in seven games. If winning is the whole thing — and it is — then 2013 was “Seven Nation Army’s” sporting high point.

Meanwhile, in college sports, the riff had spread to a point of utter diffuseness. As Chris Strauss of USA Today wrote, citing Michigan, Ohio State, and Penn State, “What good is it if three of the oldest rivals in the Big Ten are all using the same exercise to fire up their stadiums?” A song adopted on both sides of a rivalry loses meaning — it’s just noise.

Internationally, “Seven Nation Army” remained the go-to soccer anthem; during the Euro 2012 tournament it was the standardized goal song. I was in Spain during their team’s final-round victory over Italy, but I don’t particularly recall the crowd singing along as it blared over the loudspeakers. The song of the summer there wasn’t “Seven Nation Army,” but rather Sak Noel’s unbearable “Loca People.”

However indifferent Europeans had grown to it, the infestation continued unabated back in the States. Increasingly, chanting “Seven Nation Army” became a referent-less intensifier, a vehicle of pure affect, like “Rock and Roll (Part Two)” had been before it. (No doubt the revelation that the musician behind the latter was a serial pedophile sped the takeover along; The NFL issued a ban on the infamous “na na na na na—hey!” song in 2006.)

In June of 2013, EA Sports announced that a “Seven Nation Army” chant would feature in the game NCAA Football ’14 — thus completing the song’s cyclical transformation from commoditized sound into communal performance and back again. In November of the same year, 19,211 fans of the New Jersey Devils elected it the team’s new goal song, but only after the team nixed the old one, “Rock and Roll (Part Two),” because of their fans’ habit of using it as a springboard for “you suck!” chants.

A sure sign that “Seven Nation Army” had passed over into total cultural ubiquity, shedding any remainder of specificity, came in 2015, when the Foo Fighters performed the song at Boston’s Fenway Park along with frontman Dave Grohl’s orthopedic surgeon. To be clear, that’s a band that’s not the White Stripes, singing a song that’s only incidentally about orthopedics (“And the feeling coming from my bones says, ‘Find a home’”), with a doctor, in a ballpark known for a Neil Diamond song.

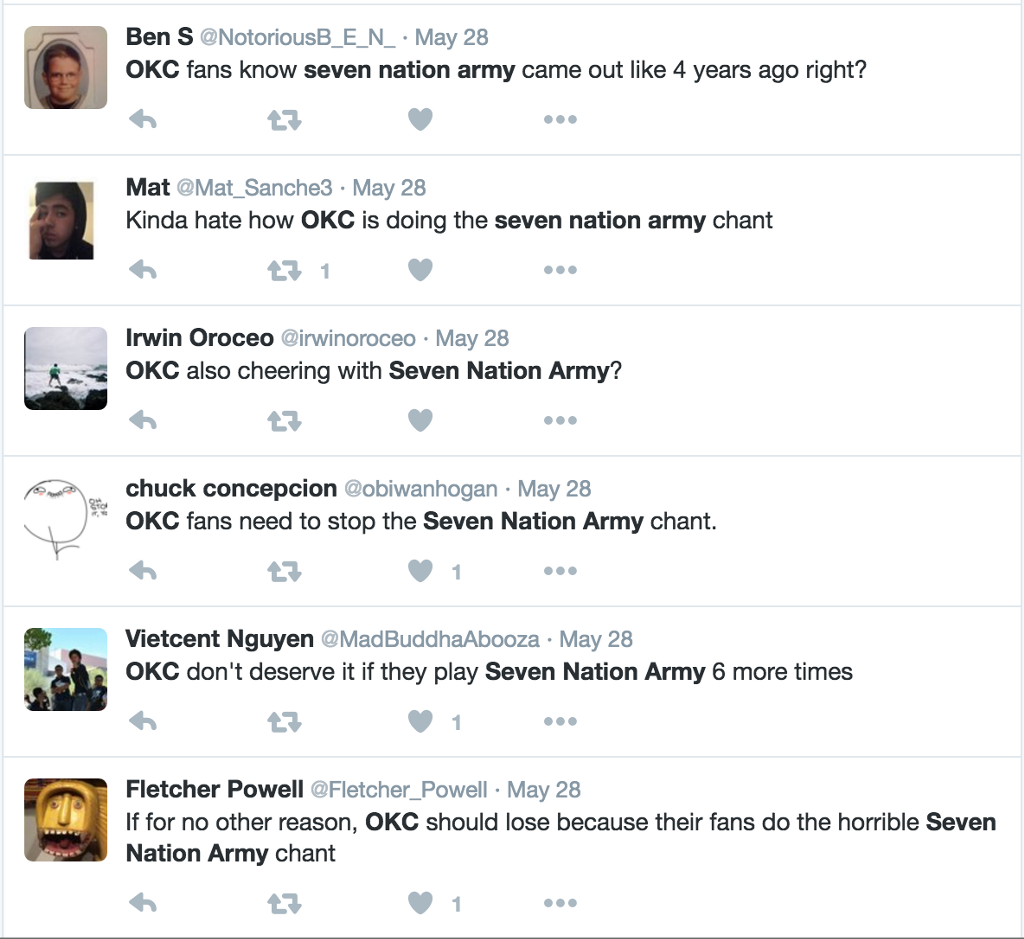

I n April, Sean Gentille of The Sporting News dubbed “Seven Nation Army” the “best possible example of a truly great song ruined by overuse.” Already in 2014, a blogger covering the West Virginia University Mountaineers for SB Nation counseled moderation in the use of the song at home games. Last Saturday night, during the Thunder-Warriors game, MTV News political writer Ezekiel Kweku tweeted:

Basketball, over the years, has made me come to hate Seven Nation Army

For his part, Jack White has embraced the phenomenon, calling it “the greatest thing that could ever happen” for a songwriter, and likening the song’s embrace by sports fans to the processes of “folk music.”

Instead, it’s maybe more accurate to hear “Seven Nation Army” and the sports empire it built as global capitalism all the way down. Originally recorded on a label founded by the mogul Richard Branson, heard by Belgian soccer fans in Italy because of globalized distribution networks, and passed from stadium to stadium in the United States thanks to an efficient legal framework that allows teams to secure the use of millions of songs by purchasing blanket licenses from just three organizations, the song couldn’t have spread as it did except under late capitalism. And, of course, deep in the foundation of The White Stripes’ blues-rock style rests the commodification of African-American music that was so much a part of accumulating the music industry’s financial clout in the first place.

Though none of this means that Jack White is wrong in every case to think that his song can feel like a bit of folk culture. Maybe in some pockets — for the supporters of Club Brugge, say — chanting its seven notes still feels specific, like something that binds together you and actual people you actually know. Maybe in some places it continues to affect and signify on a more human scale. Maybe it’s not done just yet. That’s the suspicion of the Ravens’ Jay O’Brien, anyway: “People have mentioned over the last couple years, ‘should we stop using it?’ But I think our fans would do it anyway.”

Brian Barone is a graduate student in Boston. He co-hosts the music podcast Tuner.