Cabin on the Lake

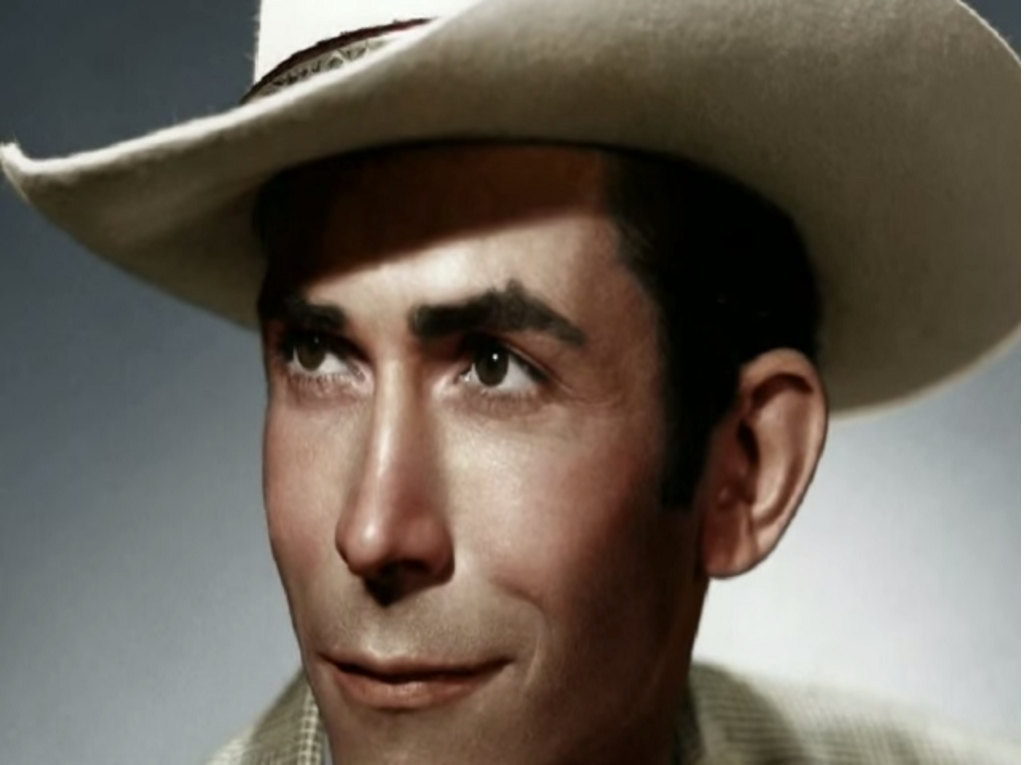

Hank Williams catalogs the shapes and sounds of loneliness.

Loneliness is liquid. It fills whatever container it can: pouring across a night or any number of days, spilling into weeks or even months, sloshing into whole years if you let it. No one understood the liquid properties of loneliness better than Hank Williams, who wrote an anthem of anguish for that fluid feeling. It was 1949, and Williams wasn’t alone, but he was lonely. His wife’s cold, cold heart had left him chilly, so he did what any songwriter does: he wrote a song.

“I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” catalogs some of the shapes and sounds of loneliness. The song’s opening chord twangs the feeling of being alone immediately into existence, conjuring so perfectly the endlessness of how it feels to feel lonely that it’s only counterpart is its opposite: the orgasmic optimism of Joan Jett’s “ah” in the first second of her cover of “Crimson and Clover.” You know right away that this is the soundtrack of a lonely heart — a man on his own, alone on his own island.

But he’s not really alone, there are other solitary sojourners, too: some birds, a nighttime train, a weeping moon, dying leaves, a shooting star, and a purple sky. Williams hears his loneliness echoed by a whippoorwill too blue to fly and a train so quiet that not even its whistle sounds; he sees it in a moon hidden by clouds and a robin whose tears mourn the changing seasons. The singer has found himself in a world without any human companionship. Not even a falling star, that wishing object of crossed lovers and lost sailors, can sustain a wish: its light only makes him “wonder where you are.”

The “you” is never named, and it’s not even clear how far, if far at all that “you” is from the singer. The song turns partly on the ability of loneliness to drown the way water can: not with fathoms, but a few inches. Hank Williams sings of the kind of lonesome you can be when the one you love is right by your side: a fight can make your man feel miles away even though he’s sitting at the table beside you; work carries your woman across the universe while she’s working at a desk across the room from you. You don’t need eternity to have come between you and love to feel lone, and sometimes you feel it most when you aren’t alone.

“I’ve never seen a night so long,” Williams howls in the second verse, and damned if you don’t believe it. He’ll say three times before the song is over that “I’m so lonesome I could cry,” but you really only needed to hear it once. Thirty seconds in and we already know for sure that we’re in the room where Mrs. Ramsay knits while her husband reads, sensing he wants her to say she loves him, but refusing, in the field where Ruth “stood in tears amid the alien corn,” eavesdropping with Prufrock on those mermaids who sing “each to each.” By the song’s final verse, “I’m so lonesome I could cry” has become a kind of spell, only the third time isn’t a charm, but a curse: Williams didn’t die of loneliness, but from another kind of liquid.

Earlier this year, I was down around where Williams tried to get clean and sober the summer before he died. He’d been fired by the Grand Ole Opry, and came to Lake Martin to dry out, but it was in nearby Alexander City that he’d be photographed all gaunt and ghostly, sad and shirtless on his way out of jail after an arrest for drunk and disorderly conduct. Williams did manage to write some songs in his cabin on the lake, including one about a lonely wooden Indian, and he recorded them in September of 1952, but by the end of the day on the first day of 1953, he was dead.

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland.