Riding In Cars With Beers

by Owen Phillips

If you ask someone from Mississippi how long it takes to drive from Jackson, the capital, down to the Gulf Coast they might tell you “about six beers.” Walk into most gas stations there and you’ll find waist-high barrels filled with tallboys (sixteen to twenty-four ounces) and hog legs (thirty-two ounces) covered in ice. The beers are located near the door, sold individually, and placed in brown paper bags for a reason. Mississippi is the only state that doesn’t have an open-container law that prohibits drivers or passengers from drinking inside a motor vehicle. And while some counties and cities have passed their own ordinances to ban the practice, Mississippi still has an abnormally high rate of alcohol-related traffic fatalities.

In Desoto County, a beer-and-half drive from Memphis, drivers are free to keep a cold one in the cup holder. Confusingly, some cities within the county prohibit it, creating what was described by Michael Cory, a practicing attorney in Jackson, as a “hodgepodge of laws.” In 2014, Desoto County tied for the most alcohol-impaired traffic fatalities in the state. “From a public safety standpoint, I can’t think of a single good reason for it [prohibiting open containers in motor vehicles] not to be state law,” Cory said.

Lieutenant Gary Ricks, a police officer with Desoto County since 1998, explained that some drivers like to have a beer on the way home from work. Drivers who partake must maintain a blood alcohol content (BAC) below the .08 legal limit. Ricks said that officers will “most likely” administer a breathalyzer test to any driver that’s pulled over in Desoto County with an open container. “But if they check out all right, we let them go,” said Ricks.

Keith Brown, a school resource officer (essentially a cop assigned to a school) just outside of Jackson, said you couldn’t pay him to “drink a wine cooler while driving.” Brown explained that even without an open-container law, officers can deduce when a driver doesn’t belong on the road. “If there is anything out of the norm that raises suspicion, even just a twinkle in [the driver’s] eye, then you as an officer are required to investigate,” he said, noting that a driver with a beer in hand would qualify as suspicious. Still, Brown conceded that passengers are free to obliterate themselves inside a car. Brown said that, in cases where a passenger is already half-gone, but the driver is sober, all he can say is, “Have a good day.”

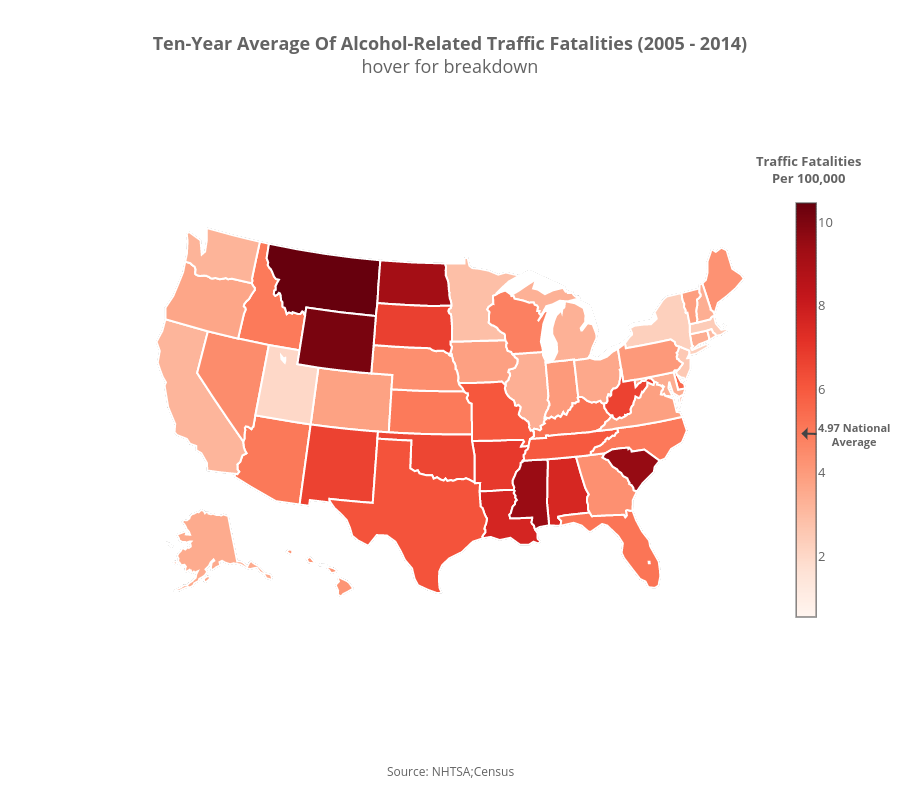

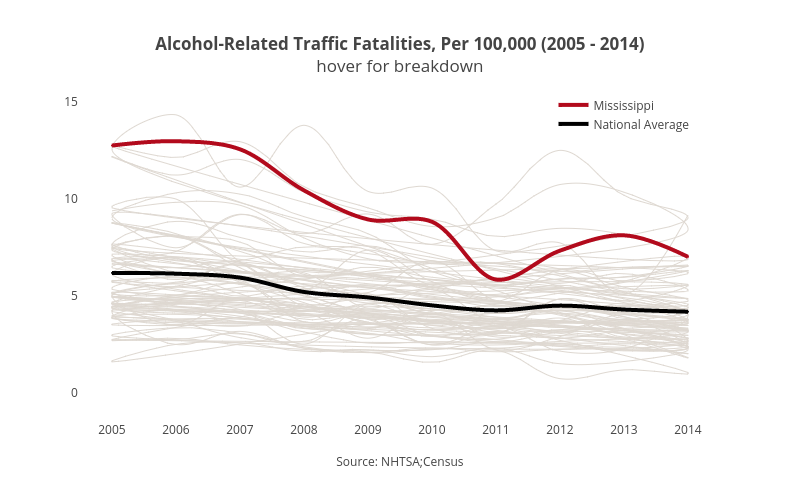

Historically, drivers in Mississippi are more likely to die in an alcohol-related crash than almost any other state. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has measured traffic fatalities, both alcohol-related and not, since 1994. (“Alcohol-related” is defined by the NHTSA as at least one driver in the crash having had a BAC of at least .01.) The map below shows the ten-year average of alcohol-related traffic fatalities per 100,000 residents for each state. From 2005 to 2014, Mississippi had an average of 9.4 alcohol-related traffic fatalities per 100,000 residents each year — almost twice the national average of 4.97.

In 2014, two hundred and seven people died in alcohol-related crashes in Mississippi. With a population just shy of three million, the state had the fourth-highest rate of alcohol-related traffic fatalities that year, trailing only North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming. (The latter two adopted their own open-container laws in 2005 and 2007, respectively.) From 2005 to 2007, the annual rates of alcohol-related traffic fatalities inMississippi were three of the worst this century.

But Mississippi’s rate of alcohol-related traffic fatalities is on the decline. As the travel writer Richard Grant remarked after living in the Mississippi Delta for his book, Dispatches From Pluto, “Things have come a long way in Mississippi, but nowhere else in America had so far to go.”

Those opposed to a statewide ban on open containers in vehicles have argued that it could exacerbate Mississippi’s impaired-driving problem, saying the ban would only encourage more drivers to stop at the bar before getting behind the wheel. At least with road sodas, or so the argument goes, a driver has some lead time before they start to feel the beverage’s effects.

“It’s a cultural thing for some of these communities,” said Eric Strickland, the Director of Federal Relations at the Governors Highway Safety Association — a nonprofit in Washington D.C. that represents state highway safety offices across the country. Strickland explained that states also face financial penalties that reverberate beyond the high rate of preventable deaths when they don’t adopt an open-container law. Mississippi loses $5 million in federal funding for highway infrastructure projects for each year it doesn’t have a statewide open-container law that meets federal standards. Instead, that money is diverted into driver-safety programs. The federal government successfully used this same tactic in the past to encourage states to adopt other common-sense standards, like the minimum drinking age of twenty-one and the BAC legal limit of .08.

If there’s any state where an additional $5 million could make a difference, it’s Mississippi, where the Department of Transportation classifies more than half the roads as either “poor” or “mediocre,” and more than a fifth of the bridges as “structurally deficient” or “functionally obsolete.” Earlier this month, the Clarion-Ledger reported that state lawmakers wrung their hands and failed to act when the chamber of commerce pleaded with legislators to raise taxes to fund the repair of the state’s crumbling roads and bridges.

It’s remarkable that Mississippi, which is largely conservative, doesn’t already have an open-container law. This is the same state that banned any beer stronger than a Sierra Nevada up until 2012. It’s also the same state where the sale of alcohol is prohibited in over a third its counties, and where some stores, until recently, sold their beer warm to discourage binge drinking. This year, Republicans held an across-the-board supermajority in both the state House and Senate. The one piece of legislation that aimed to prohibit the possession of an open alcoholic beverage in motor vehicles was sponsored by a Democrat; the bill never made it out of committee.

Photo: Juan Fernandez