Refugees In Greece, Waiting For The Unknown

by Max Rothman

Over the past winter, Abdelkader Tebri had only known stasis. The twenty-one-year-old Algerian woke every morning in Athens, Greece, without a plan. “I’m stuck in here,” Tebri said. “I try many, many, many things. I wait.” Tebri’s struggle is familiar for young migrants from the Middle East: They leave Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, or other strife-ridden countries, ride shoddy boats from western Turkey across the Aegean Sea to a Greek island such as Lesvos, Chios, or Kos, and then are scooped up by a ferry from Piraeus, a seaside town just west of Athens. From there, they are put on buses and taken to shelters and camps throughout the country, most often the overflowing camp in Idomeni, a northern Greek village on the Macedonian border, where they wait.

Refugees face barriers at every stage of the trail to northern Europe, where most hope to wind up. On November 18th, western Balkan countries such as Macedonia, Serbia and Croatia opened their borders only to refugees from Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan, who were required to seek asylum exclusively in Germany or Austria. At the end of February, border officials began denying Afghans as well. Throughout March refugees have been stuck in Greece regardless of nationality. Despite the restrictions, all through the winter, young men from Algeria, Morocco, Pakistan and Yemen among others left their homes in search of work, education, opportunity, and freedom, often with forged documents in hand. “We all want to be Syrian or Iraqi,” Tebri said. “We change our nationality. It’s not good thing.”

This past winter, when the border was open to refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, most migrants from other countries learned about the restrictive policies only after they had already arrived in Greece. So in camps throughout the country — Omonia and Victoria Squares in Athens, and the ports in Piraeus — thousands of young men sat around, frozen in place. They waited for many things: a new policy to grant asylum to people from their country; a money wire for a bus ticket; identification documents; family not far behind; or the right time to try sneaking past the border.

Abdelkader Tebri, 21, from Blida, Algeria, poses with someone else’s bike in Piraeus, Greece. “The government don’t care about me,” he said. “If I told them I’m from Algeria they take me to the jail or they take me back to my country. I don’t want that.”

Over three weeks in January and February I met many young migrants while assisting refugees who were stuck in or passing through Idomeni and Piraeus. Most didn’t know what to do: They couldn’t pass the border, but home was too dangerous or too impoverished. During my second week in Greece, I shared a table outside an alley bar in Piraeus with Tebri, Salman Alsharaaby, a young man from Sana’a, Yemen, where air strikes continue to ravage daily life, and Alaa Mohammed Shousha, a thirty-seven-year-old electrician from Baltim, Egypt. Tebri and I drank Fix, a Greek lager, while Alsharaaby and Shousha drank coffee.

Tebri explained how he had managed to cross the Aegean, scamper through forests and over mountains near the Macedonian border, and sneak into Tirana, the Albanian capital. He was sent back to Greece when his friends got into a fight and were caught by police, and he has failed to gain asylum. Eyes sunken from constant anxiety, Tebri spent hours every day wondering how to find somewhere to live. “I start to lose my mind,” he said. “If I stay here long time I will be crazy. I will be crazy.”

Alsharaaby followed his mother’s demands to leave home after a drone crashed and killed his twenty-one-year-old brother, Anass. He arrived in Athens in February. His counterfeit papers in hand and his lines memorized, he told a refugee camp worker that he was from Basra, Iraq. “Where exactly in Basra?” she asked. He told her the street. She had grown up on that same street, she said. His story collapsed. Stripped of his Iraqi papers, Alsharaaby was sent to prison, where guards beat him and barely fed him. Five days later and free, Allah, he said, would show him the next path.

Some have been luckier, having at least tasted life on the other side. Shousha enjoyed six years of working in Paris. “When you live in Paris you can’t live again in Egypt,” he said. Officials seized his fake passport and planned to deport him after a hospital visit in the winter of 2010. Desperate, Shousha paid a smuggler three thousand euros for Italian documents that never materialized. By the time Shousha realized he’d been tricked, the money was gone. Seething yet determined, he crossed the French-Italian border anyway, only to be promptly busted and sent back to Egypt. He has since tried acquiring visas for Spain, Serbia and Croatia, all denied. After a few years of working in Istanbul, he went to Athens. Finding the northern border also closed, he sat at port E7 in Piraeus and, with a couple new friends, calculated on someone’s iPad the sizes of mountains and forests they must cross in Greece and Macedonia to reach northern Europe.

Greek homeless and stuck Moroccans and Algerians pass the time at port E7 in Piraeus. Photo: Madeleine Png

A few of the E7 regulars detailed the dangers of the forests to newcomers. Throughout the land that encompasses the Idomeni refugee camp at the Greek-Macedonian border, not far from the Eko gas station that recently served as a makeshift camp of its own, migrants inhabit the woods and the unoccupied summer homes that layer the hills. They elude wolves, border officials, and the mafia, which robs, beats and sometimes kills illegal migrants who lurk among the trees. One of the migrants living in the forest, a nineteen-year-old from Somalia named Bilal, said he wanted to become a German citizen. Özil, his favorite player on Arsenal F.C., his favorite football club, was born in Germany. Bilal’s father, a member of the Somali parliament, ordered him to flee their home country so he could escape the Al-Shabaab terrorist organization, which targets political families. The winter nights and unabating winds can be brutal for those conditioned to equatorial climates. “It’s difficult,” he said of the cold, of waiting for a smuggler, “but I have to survive. I have to survive.”

The railroad tracks by the Idomeni camp serve as the nexus between the temporary worlds of legal and illegal migrants. Photo: Eniola Itohan

Umer, an affable Pakistani who walked alone in the forest, mapped his journey north from Idomeni through all of Macedonia. Raja, another Pakistani, with a twig perched on the front of his winter cap, limped nearby in blue Airmax shoes, laces untied, around a feta tin turned firepit. He grimaced as he trudged through the woods and recalled the anonymous shooter who put a bullet through his right ankle. He left Pakistan because of the omnipresent threat of death — at the market, on the way to work, on the way home. “Go there in Pakistan and see how people there are dying day by day,” he said. He spoke of the Peshawar school attack that left a hundred and forty-one dead in December 2014 and recalled the Pakistani constitutional amendment in 1974, which declared Ahmadis such as himself as non-Muslims, effectively turning them into targeted, second-class citizens.

Raja, an injured man from Pakistan, faces the woods by the Greek-Macedonian border. “You don’t know,” he said of life in Pakistan. “Either you are coming back to home or you’re going to die.”

Multiple breeds of uncertainty stretch from the northern border to the precarious concrete of greater Athens. On one of my last days in Piraeus I walked to port E1, the site of a volunteer warehouse at the other side of the mile-long harbor from E7. After the arrival of a ferry with a few hundred refugees, a trio of clowns lollygagged with impatient stragglers who waited at E1 for the northern border to open. One of the clowns, with an oblong face and rosy cheeks, pulled his suspenders above large white buttons and wiped his hands clean. He toted a briefcase and placed it on the floor by his size-twenty shoes, then flipped a toothbrush cane style around his index finger and helped a custodian sweep the floor with it. A Syrian boy, arms akimbo, stood magnetized before him.

At port E7 in Piraeus a concussed Algerian rests in the corner of a waiting room, which is open only during the day. At night, he joins his friends on the cold concrete. Photo: Madeleine Png

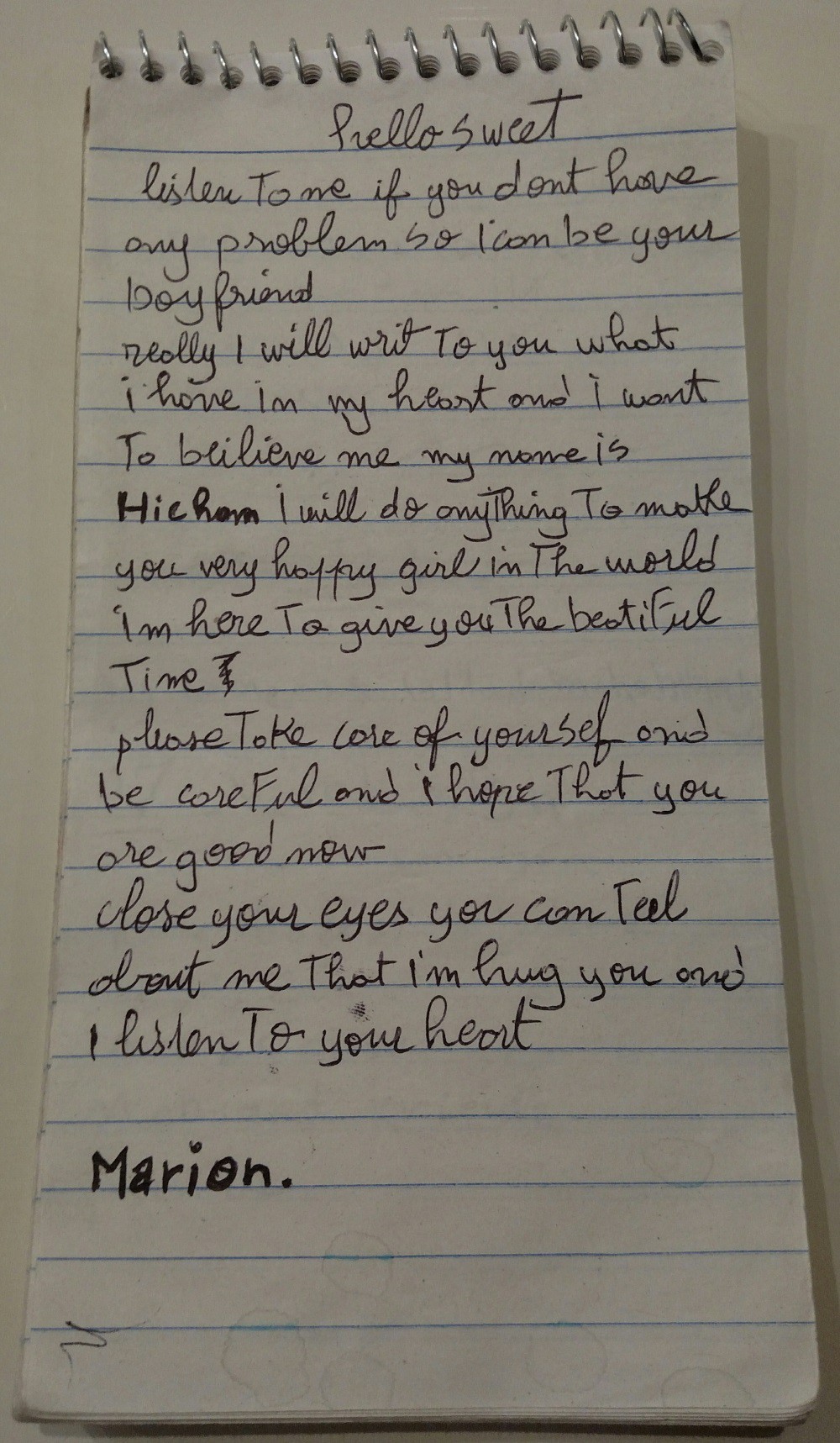

At E7 a young, concussed Algerian with woozy eyes and a neck cast requested a doctor. His friends said that, while sleeping, he took a cinder block to the head. They openly dreamed about paradise elsewhere. One, with a face Picasso would admire, spoke incessantly of New York. Another, the only English speaker in the crew, wrote love letters to distant women for him and other aspiring husbands.

“hello sweet

listen To me if you dont have any problem so I can be your boyfriend

really I will writ To you what i have in my heart and i want To beilieve me my name is Hicham i will do anything To make you very happy girl in The world im here To give you The beatiful Time

please Take care of yourself and be careful and i hope That you are good now

close your eyes and you can Feel about me That im hug you and I listen To your heart

Marion.”

When I left, many of the young men I met were still waiting at the ports, the camps and the forest for imagined future wives, new identities, a new way north, a golden chance. “I wait, that’s all,” Tebri said. “I wait. But I don’t know what I’m waiting for.”